by Mark Schniepp

January 2022

Into January 2022 we go and the pandemic continues; its future progression (or how long governments will continue to maintain a state of emergency in the name of public health) is uncertain. We generally believe the pandemic will be brought under control and that the disruptions and frictions it has caused in the labor market and to the supply chain will be resolved over time.

Into January 2022 we go and the pandemic continues; its future progression (or how long governments will continue to maintain a state of emergency in the name of public health) is uncertain. We generally believe the pandemic will be brought under control and that the disruptions and frictions it has caused in the labor market and to the supply chain will be resolved over time.

While inventory imbalances are now dissipating, they remain troublesome. Financial imbalances are manifesting in unwanted inflation which will precipitate more fiscal tightening in 2022.

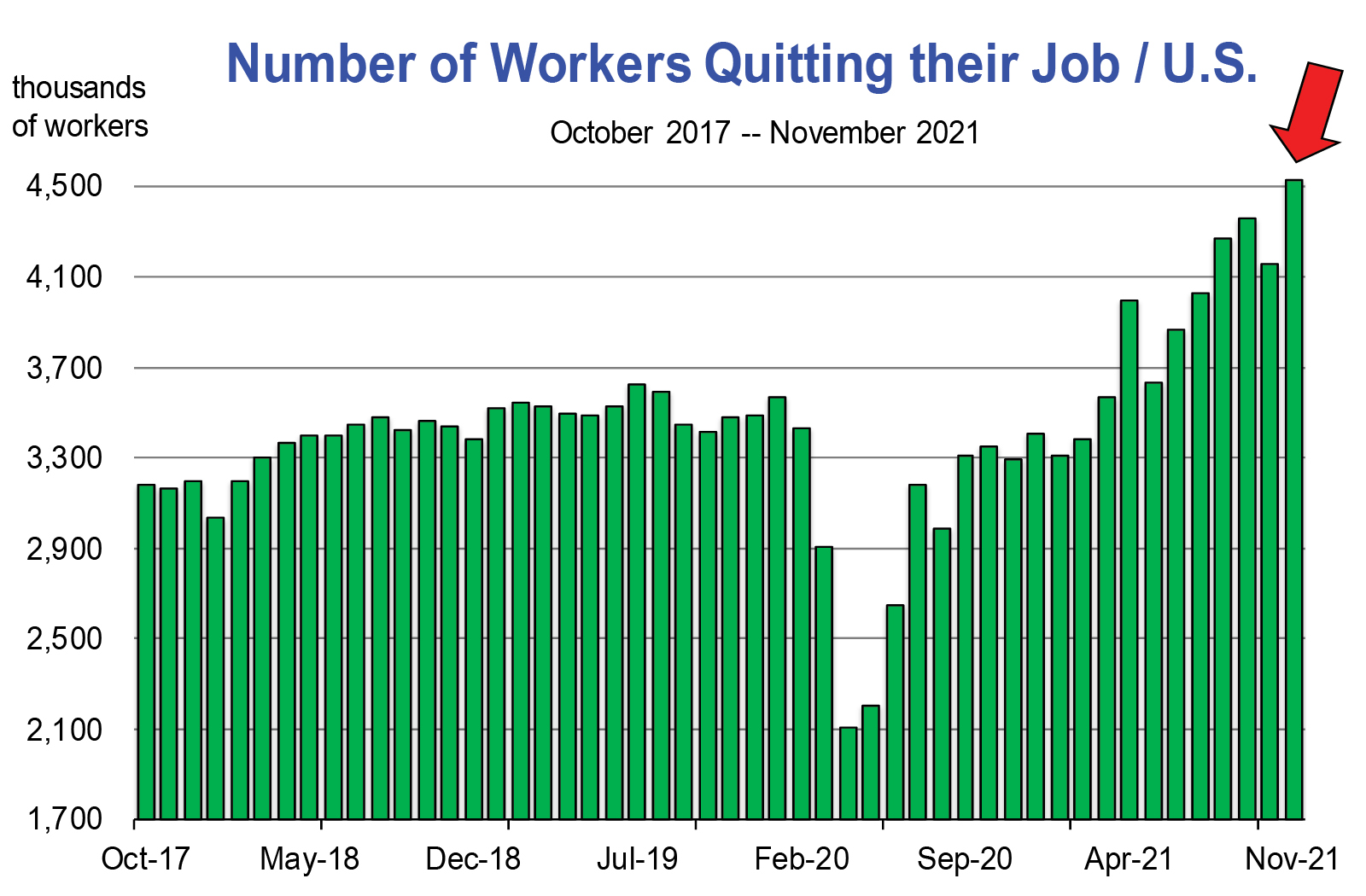

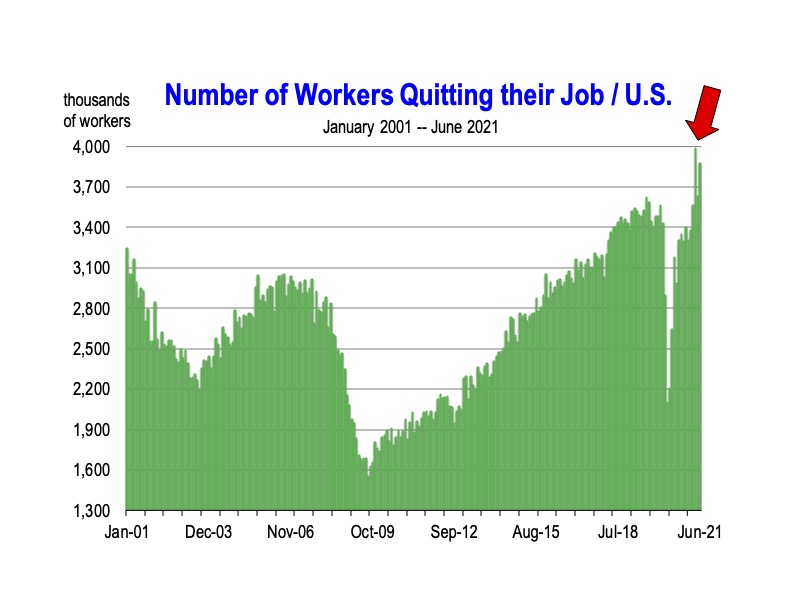

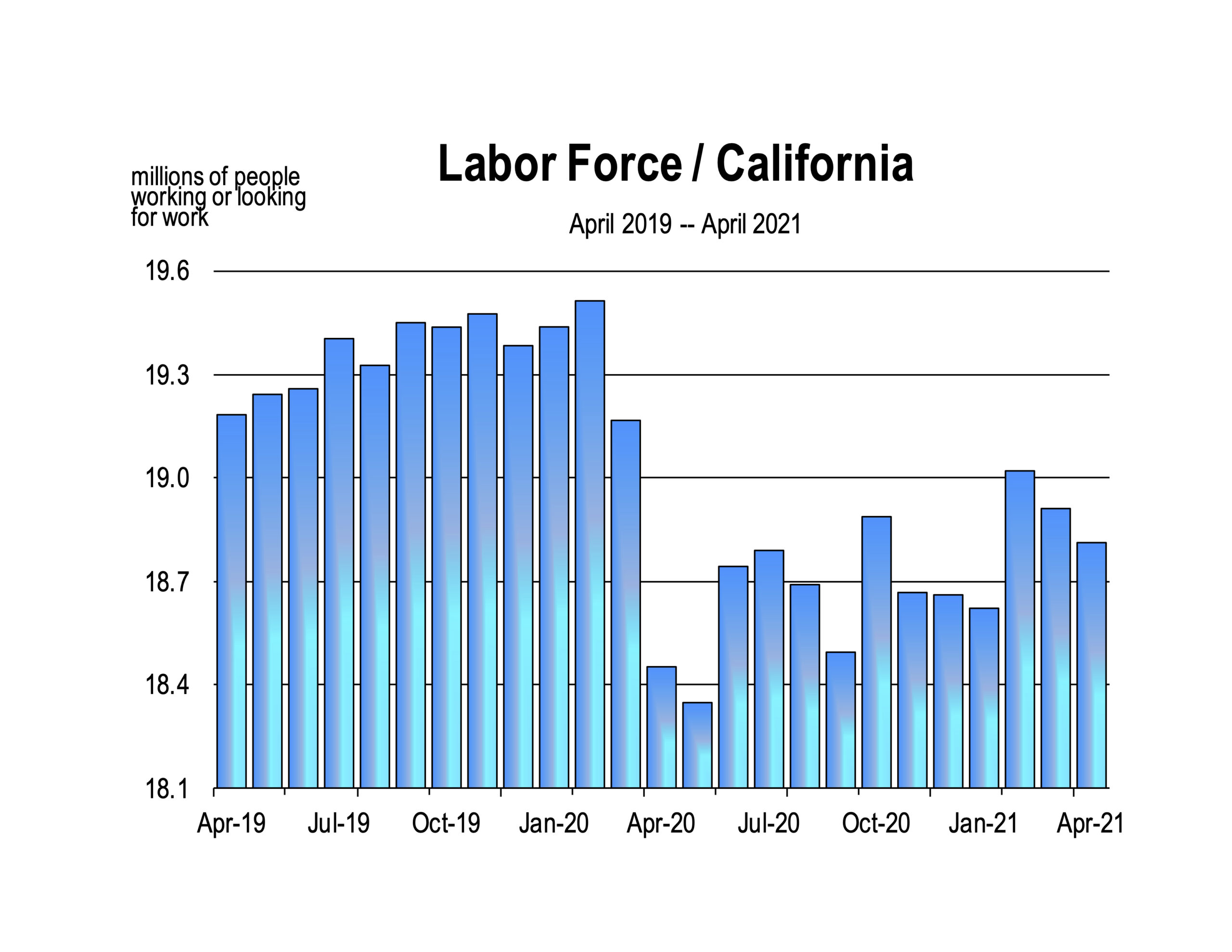

The pandemic’s disruption on the labor market was originally catastrophic but conditions have dramatically improved, and for some regions of California the labor market is back to its pre-pandemic status. But not yet in the principal metro areas. In general however, it’s not that people can’t find a job, it’s that they don’t want to work.

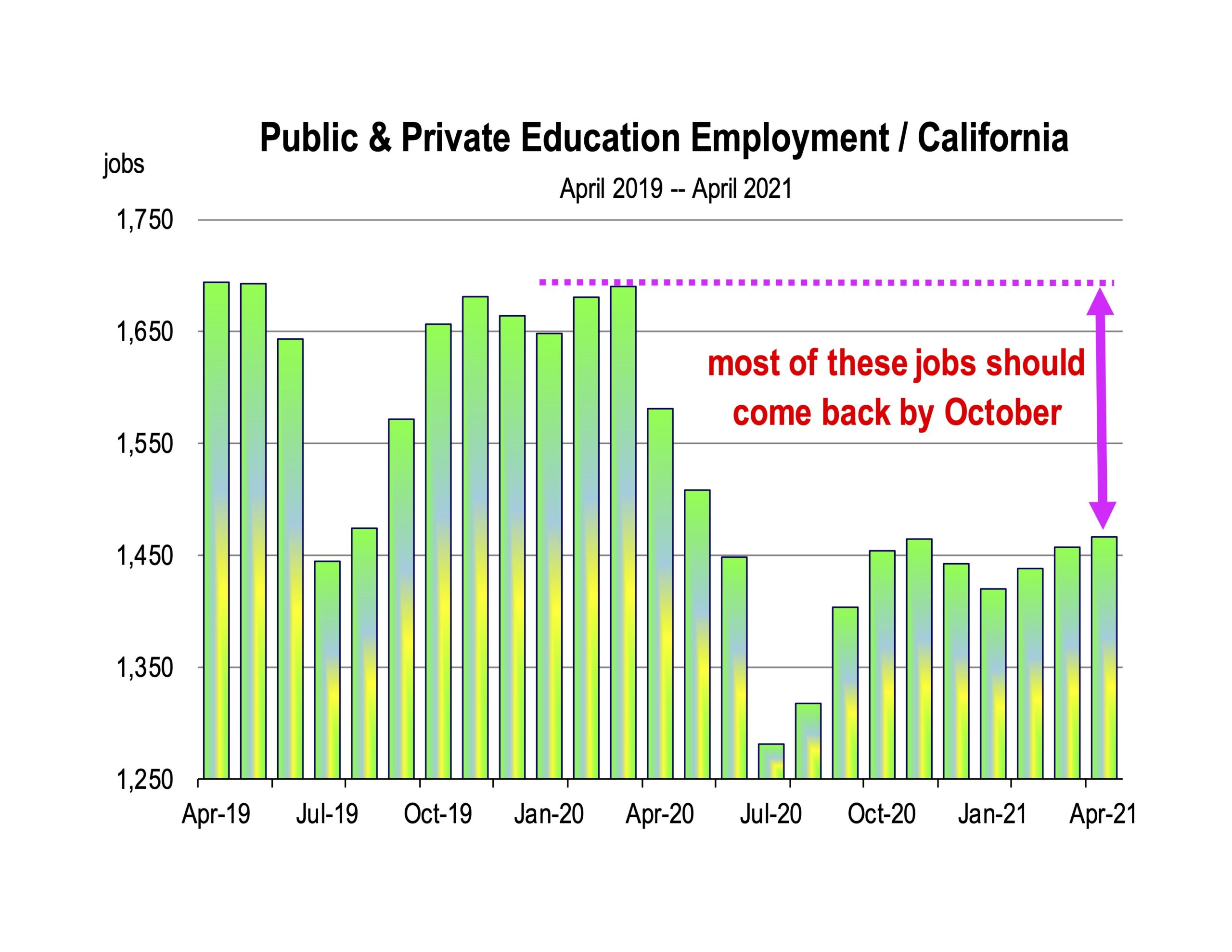

The return of many workers who had left the labor market during the pandemic because of childcare or eldercare responsibilities will take place over a longer period of time than was predicted earlier in 2021. We had expected that the reopening of schools in August and September last year would bring a large influx of parents who had been unable to work back into the labor force. Other workers are staying out because of illness, concern over the virus, or excess saving built up in 2020-2021 due to stimulus checks and/or the federal unemployment bonus. Furthermore, about 2 million more workers than expected ended up retiring.

Navigating a New Normal

Though we believe the labor force will ultimately come back, for now fewer people willing to work is looking like a new normal. Also, just-in-time production, transportation and inventory schedules will be restored world-wide. But not yet. Until these conditions of the “old” normal return, we are navigating a new normal in 2022:

Accepting substitutes for products we can’t get

Accepting substitutes for products we can’t get- Substituting into less costly goods because of inflation

- Producing goods and services with fewer workers

To date, the pandemic has accelerated some trends that were already developing:

- The share of online shopping and home delivery in consumer spending has surged since the pandemic began in March of 2020. There are few signs that this is abating and economists do not generally believe it will.

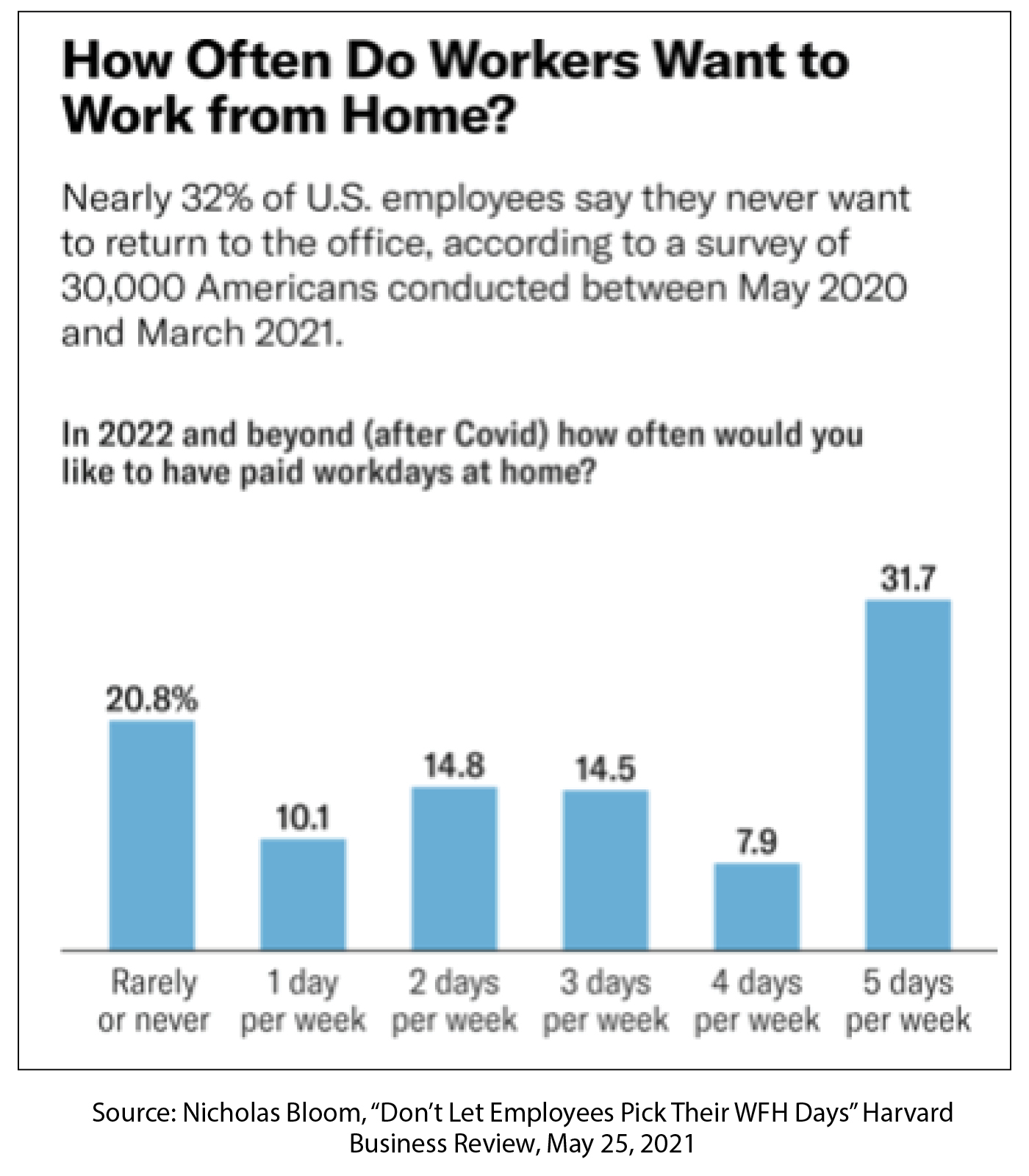

- The number and share of remote workers in the workforce has expanded substantially over the course of the pandemic. More hybrid remote work has become the current norm in many industries. There is a debate as to whether this will remain.1

- The expansion of remote work has weakened the traditional bonds between where people live and work, causing an acceleration of out-migration of some remote workers from the urban core to the suburbs and exurbs where more housing options are available, including more affordable options. This is a trend which has led to rising rents and home prices in outlying urban areas. It has also led to more demand for goods and services in these areas.

- It may lead to a situation where these remote workers may not be able to change jobs as quickly as they could if they had remained in the locational center of the job market, such as San Jose, Downtown San Francisco, Downtown Los Angeles or Playa Del Rey. If labor markets soften, will spatially remote workers who either become unemployed or want to switch jobs navigate into other opportunities readily?

The two principal conditions—remote shopping and remote working—are going to be with us for the long haul. The extent of remote shopping is likely to only accelerate. The extent to which remote working characterizes the workplace may well diminish over time. But we are speculating on this because right now, this is the normal rather than a new normal.

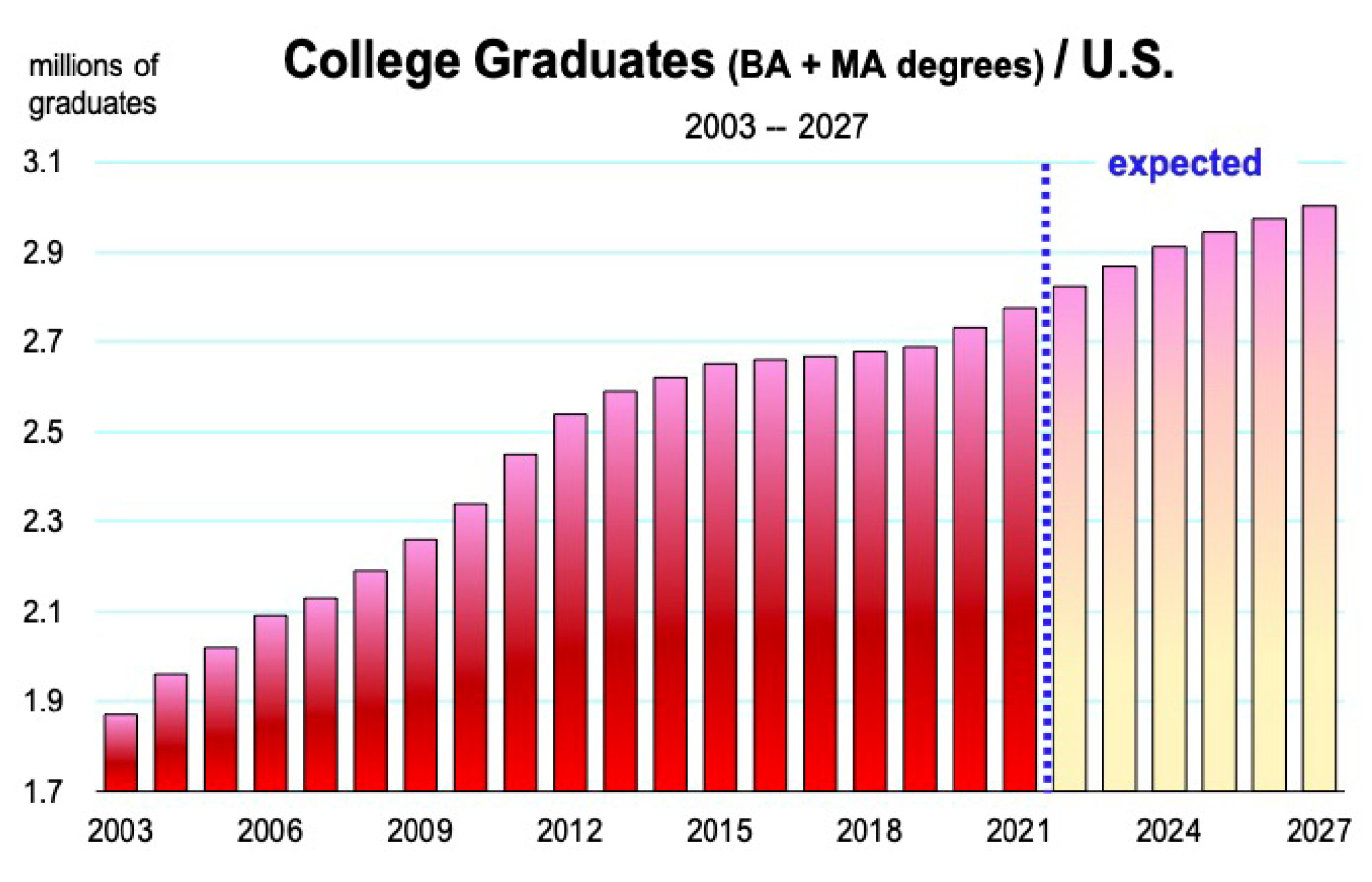

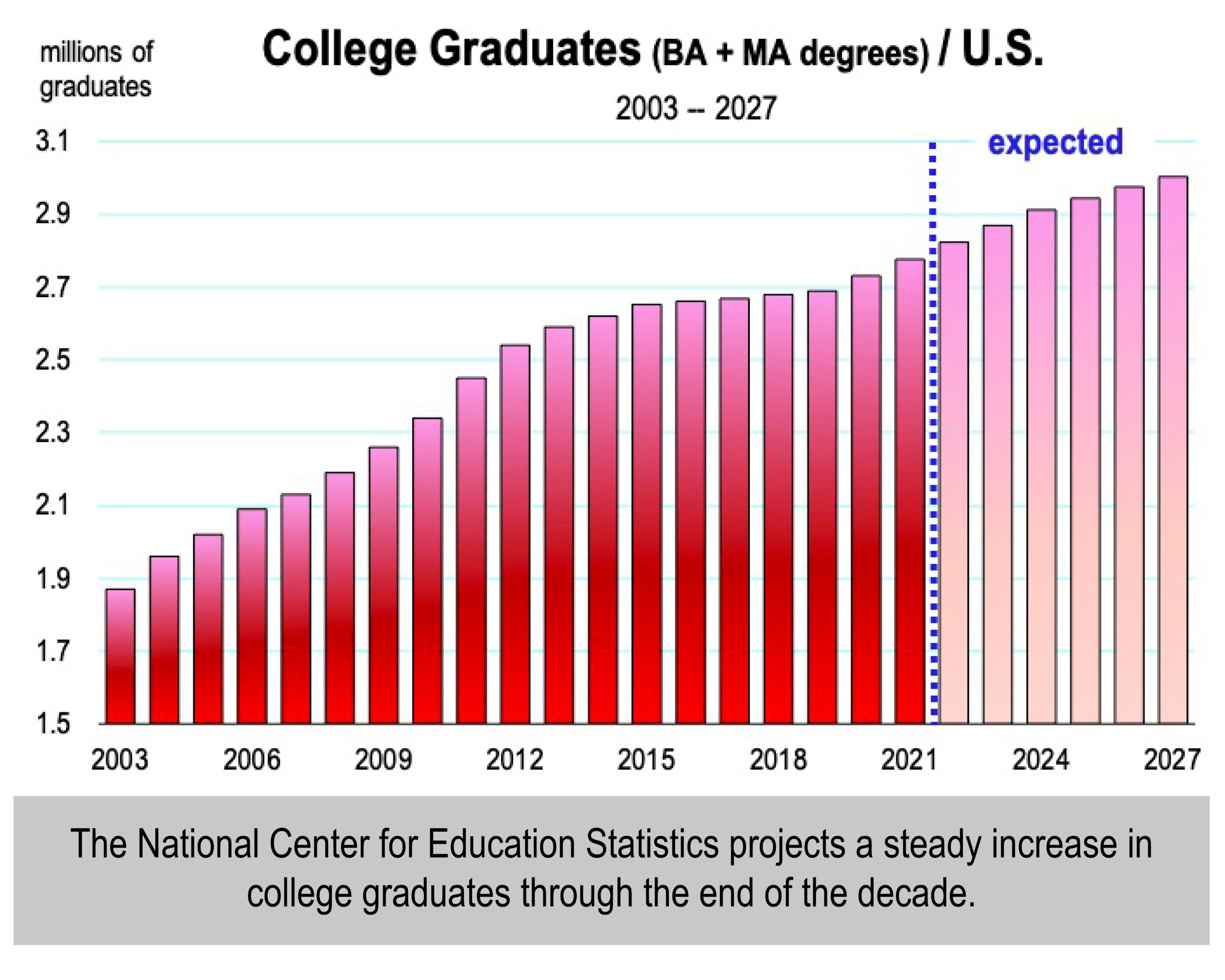

Some supervisors are uncomfortable with the out-of-sight reality of people working from home. Will companies let go of control or will they mandate at least a hybrid schedule? This may depend on how quickly the labor force returns and expands from the record numbers of new college graduates. Surveys indicate that entry level workers want to be in the office and not at home.

Are all the new variants and all of our emphasis on positive cases the new normal?

It appears so, and with this concern is the attendant impact on the economy. More than 2 million workers say concerns about getting or spreading COVID-19 are their main reason for not working.

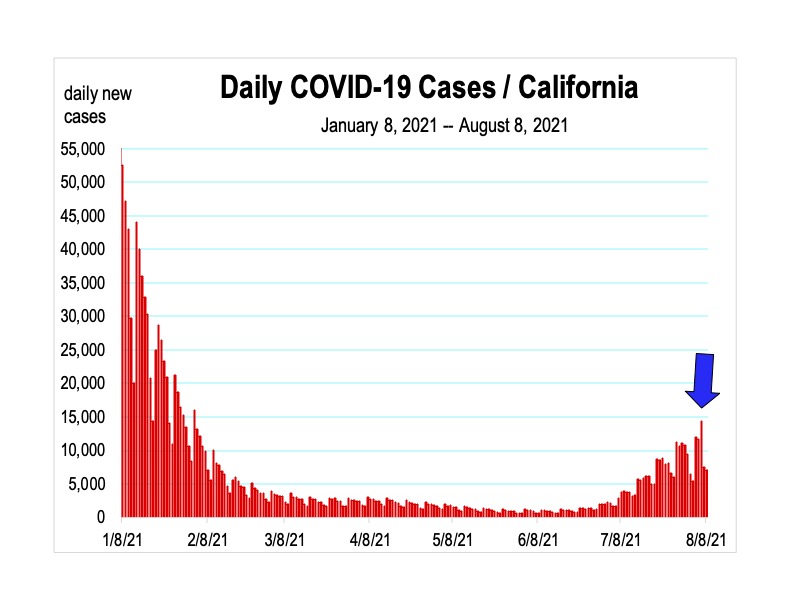

The Omicron wave has intensified, and it (as did Delta) appears to be keeping many of these people out of the labor force. Daily positive cases have now reached an all-time record high. And it also appears to be interrupting economic growth in general:

- Credit card spending has softened in recent weeks, especially for travel

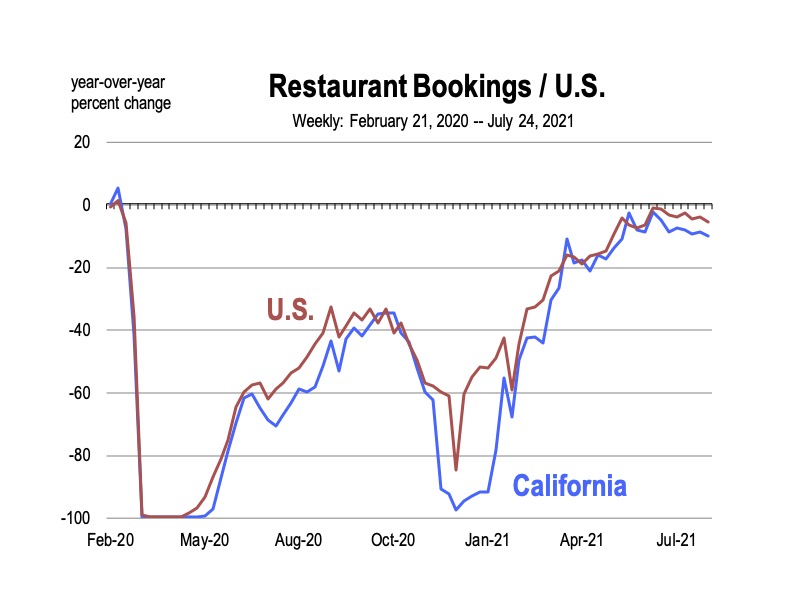

- Restaurant bookings have now moved lower

- Companies are suspending their return-to-office plans, and

- More schools are moving back to virtual instruction during the first weeks of January

Omicron will delay returning workers to the labor force and it could delay product deliveries and services. And to date, we have not seen any reason to believe that upcoming variants will elicit a different response by the media or public health officials, which in turn, panics consumers. Oh no, and now here comes the IHU variant . . . . 2

Therefore, the normal for 2022 could be a continuation of economic interruptions that hamper growth and keep it from reaching its maximum potential, given the capital and labor resources we would otherwise have available for productive utilization.

That said, we can expect variants to continue emerging, raise infection levels in the population, and then recede. We are in the fourth wave of the coronavirus. Omicron appears to be the most transmissible but the least serious. We can only hope that the seriousness of future variants continues to fade and the elusive herd immunity that we’ve been promised is forthcoming sometime this year. But for now, the variants are a daily topic of conversation that will continue to be indefinitely.

1 “Why Working from Home Will Stick,” by Jose Barrero, Bloom, Nicholas and Davis, Steven, Working Paper January 21, 2021. 50 percent of the U.S. workforce has the ability to work from home. The authors expects 40 percent of these workers to go hybrid and 10 percent to remain fully remote.

2 https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2022/01/05/new-covid-variant-b-1-640-2-ihu-identified-france-what-it/9101249002/

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.

These are the four biggest issues that we, as consumers and businesses are facing in 2021. Moreover, these issues will not be resolved by year’s end. An escalation of at least two of these issues is likely, given that we’ve seen very little resolution to date.

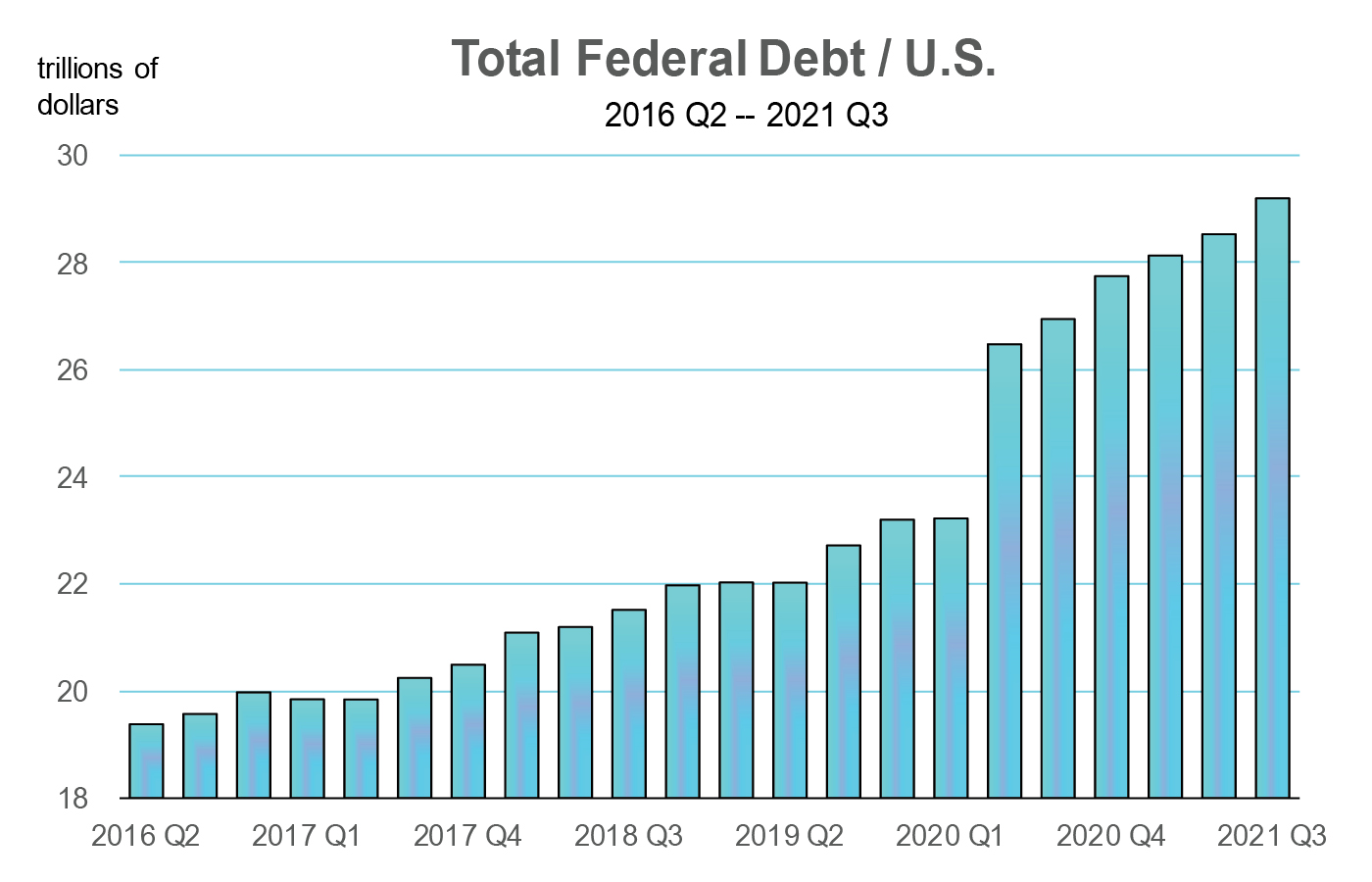

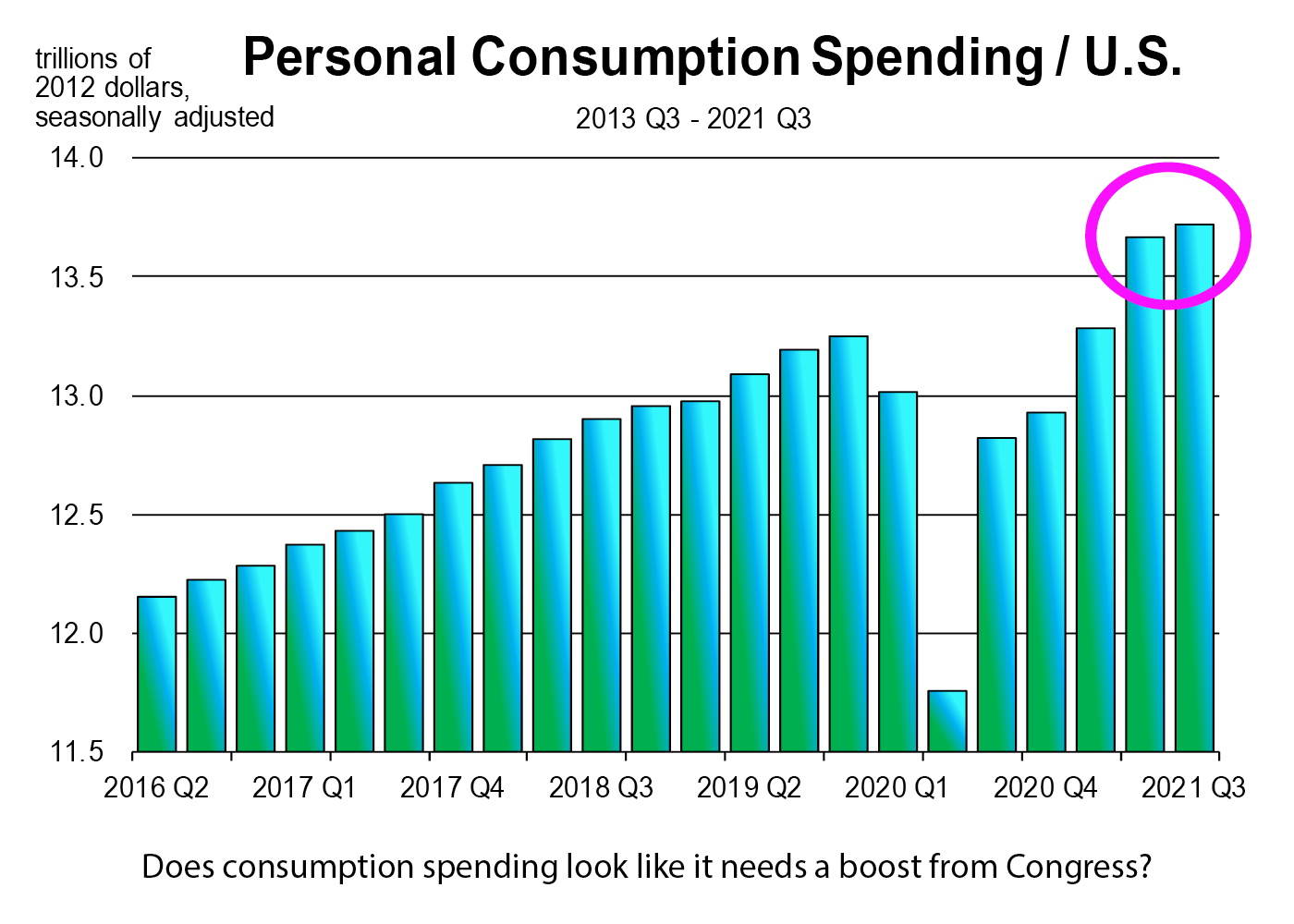

These are the four biggest issues that we, as consumers and businesses are facing in 2021. Moreover, these issues will not be resolved by year’s end. An escalation of at least two of these issues is likely, given that we’ve seen very little resolution to date. The current Congress has already passed $3.1 trillion in spending bills this year, creating not only a surge of federal debt, but a potential surge in government spending which is front loaded for 2022, 2023, and 2024.

The current Congress has already passed $3.1 trillion in spending bills this year, creating not only a surge of federal debt, but a potential surge in government spending which is front loaded for 2022, 2023, and 2024.

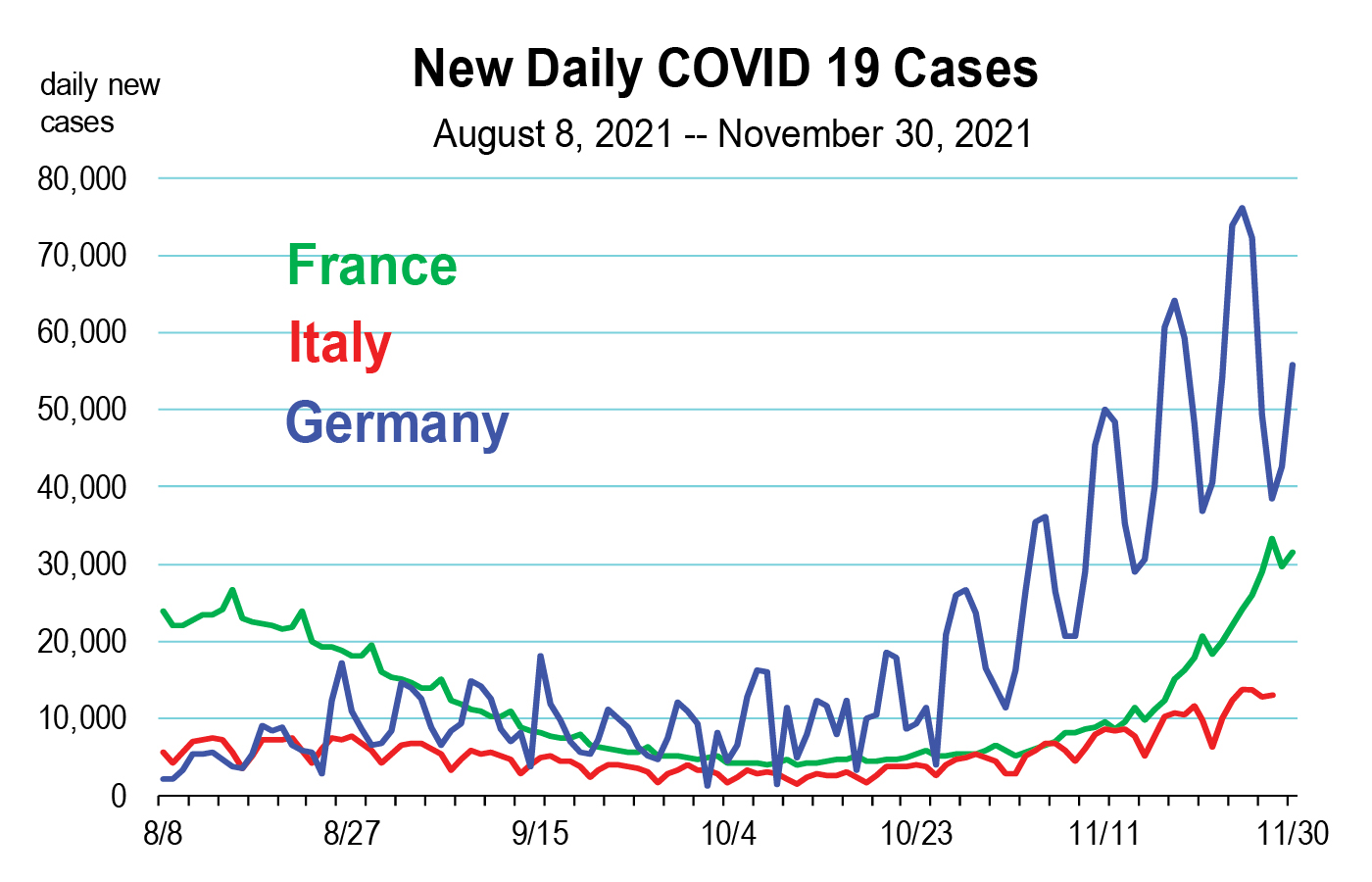

The global economic recovery remains tethered to the pandemic. And another wave is coming. We are seeing it in Europe, notably Germany and Austria. In Austria, a vaccine mandate and a national lockdown have now been imposed. In Germany, daily cases are now more than twice as high as they have ever been during the course of the entire pandemic.

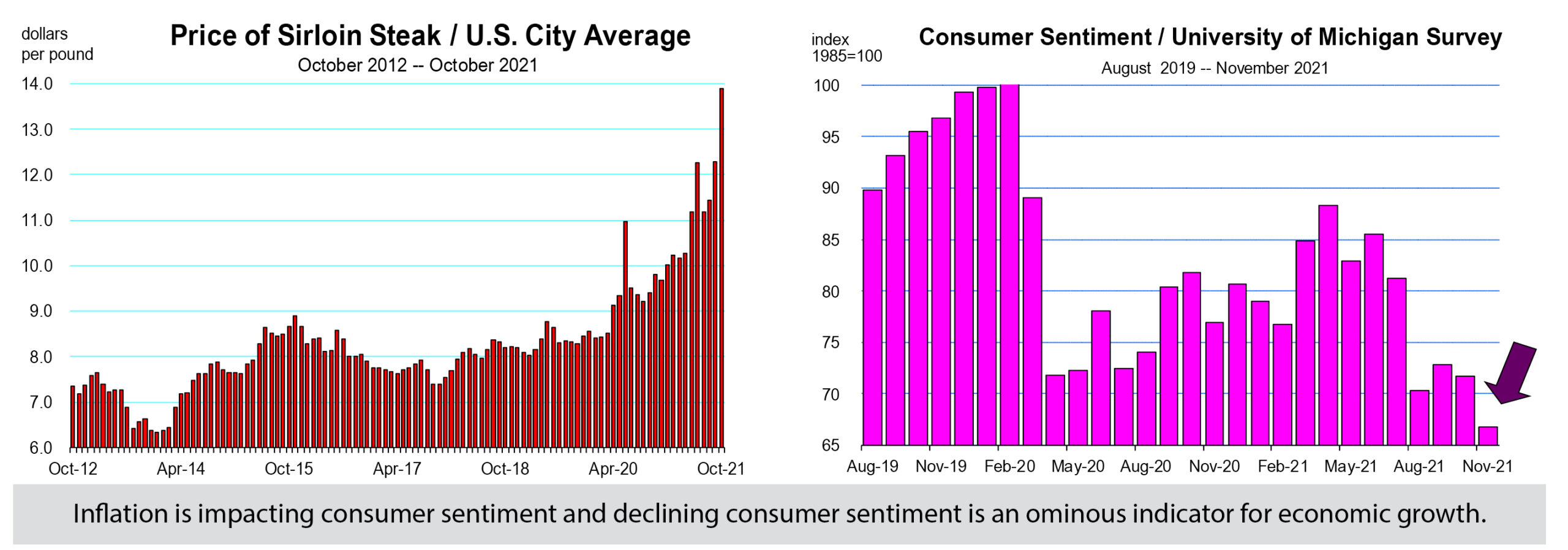

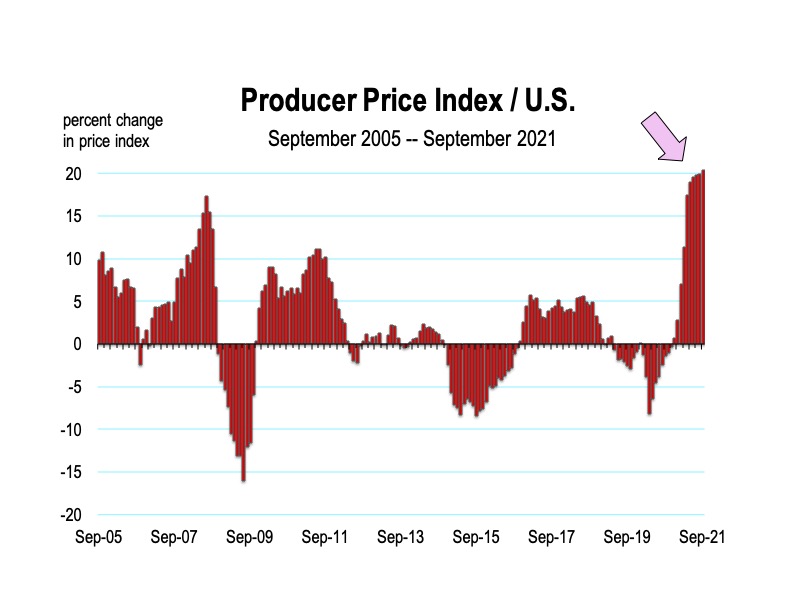

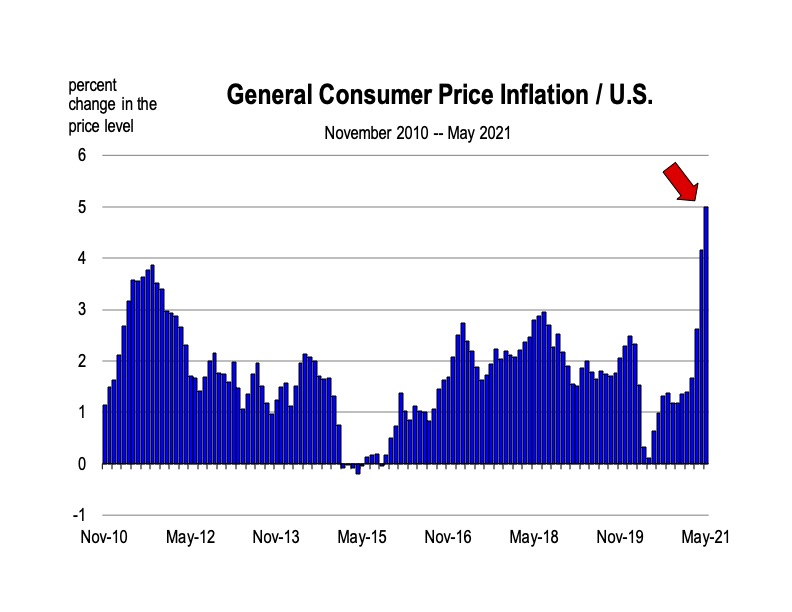

The global economic recovery remains tethered to the pandemic. And another wave is coming. We are seeing it in Europe, notably Germany and Austria. In Austria, a vaccine mandate and a national lockdown have now been imposed. In Germany, daily cases are now more than twice as high as they have ever been during the course of the entire pandemic. Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974.

Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974. The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

But what’s the chance?

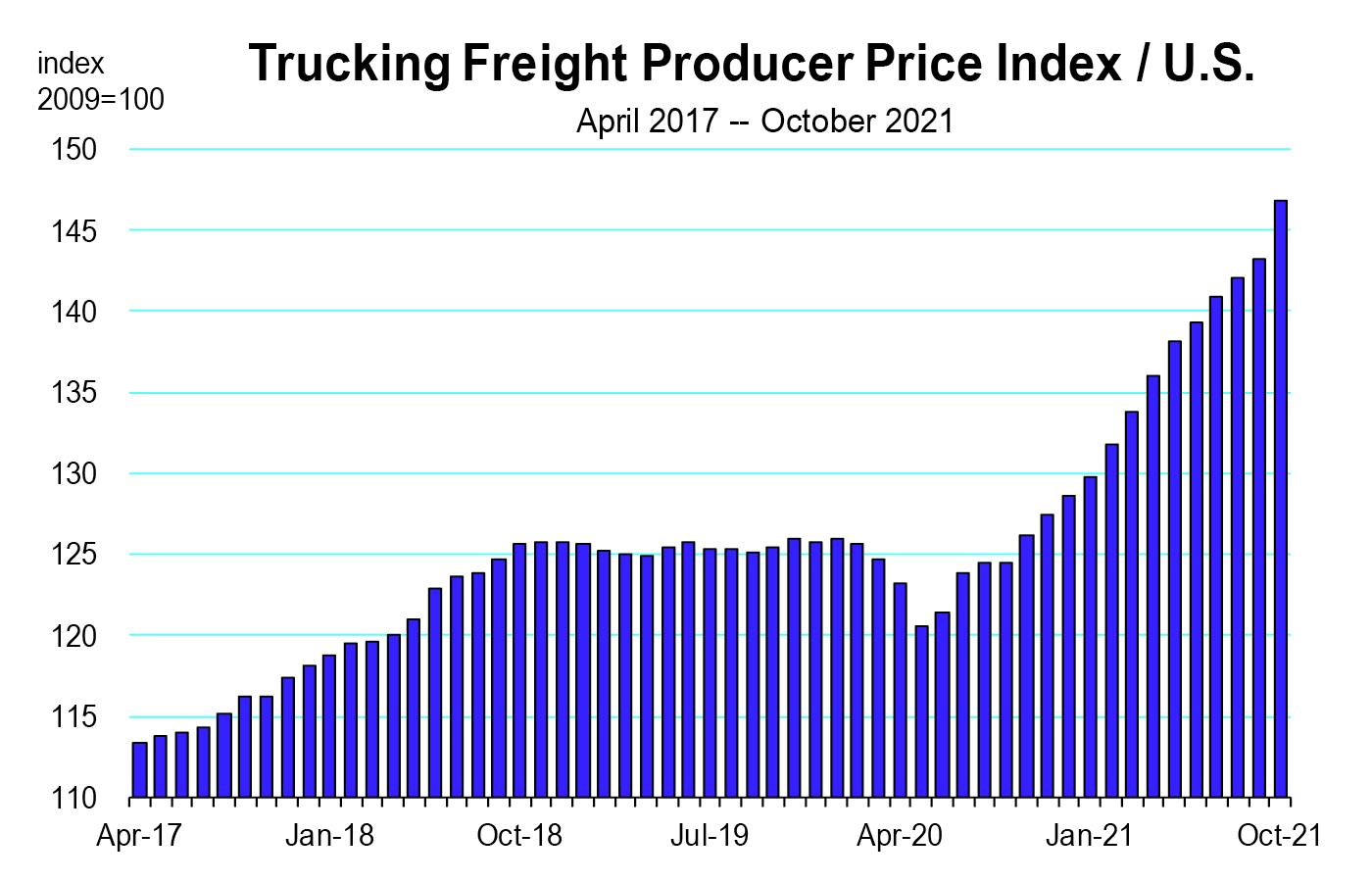

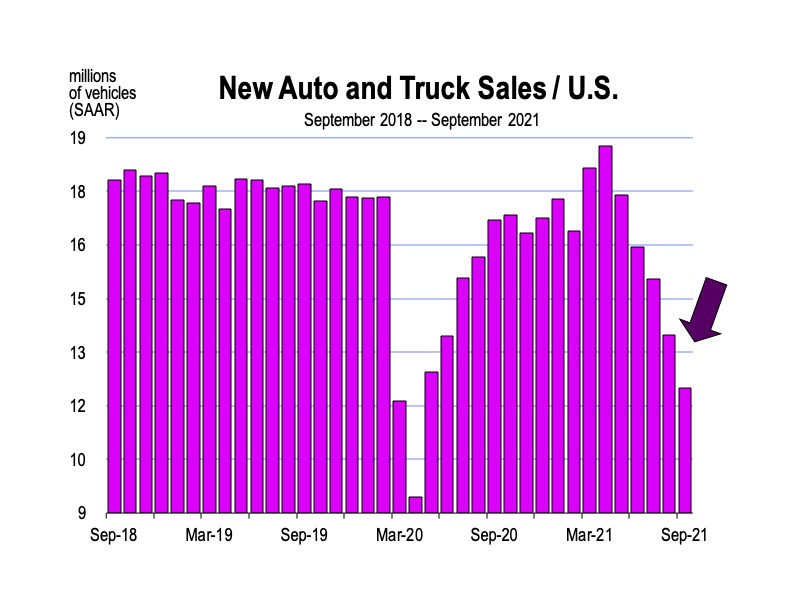

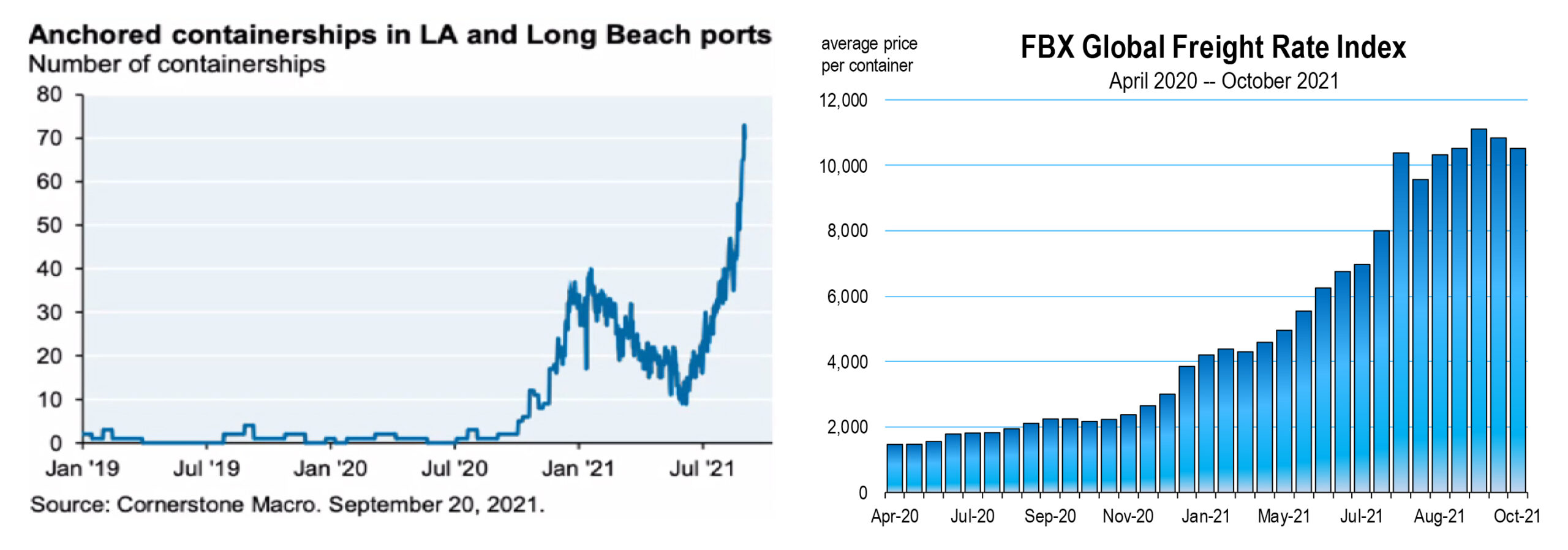

But what’s the chance? Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

by Mark Schniepp

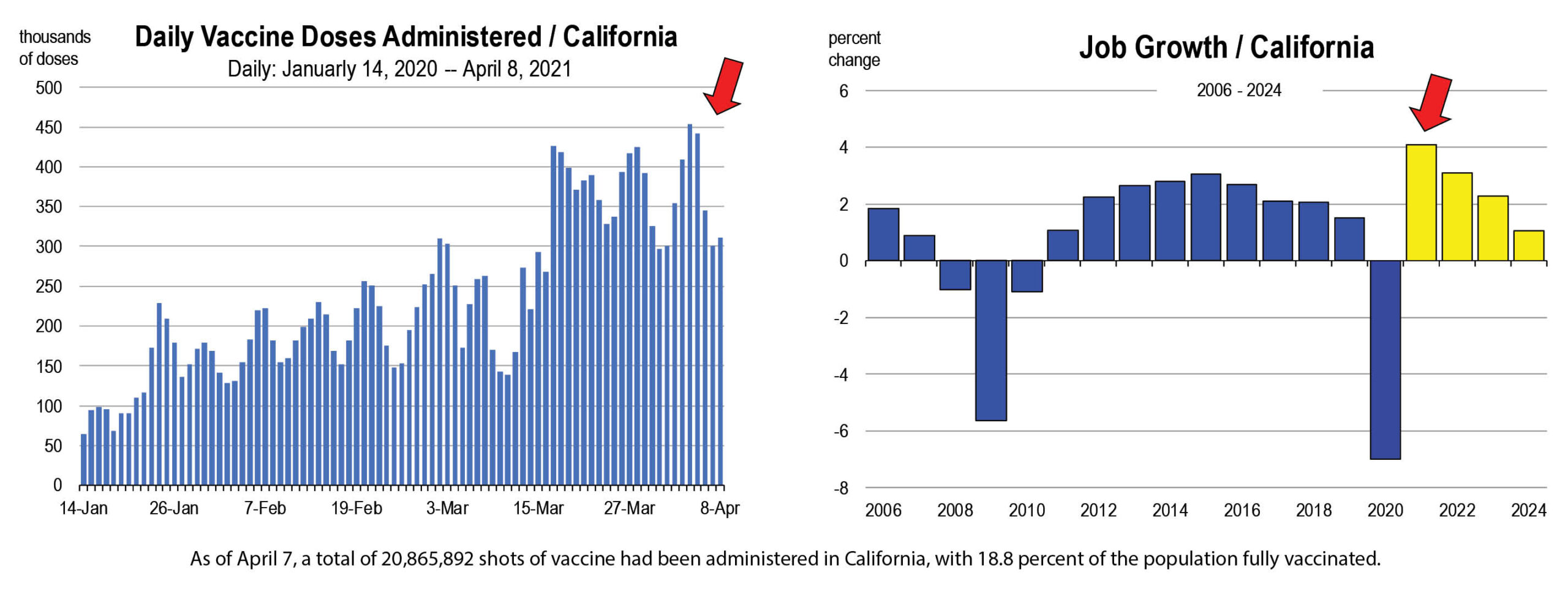

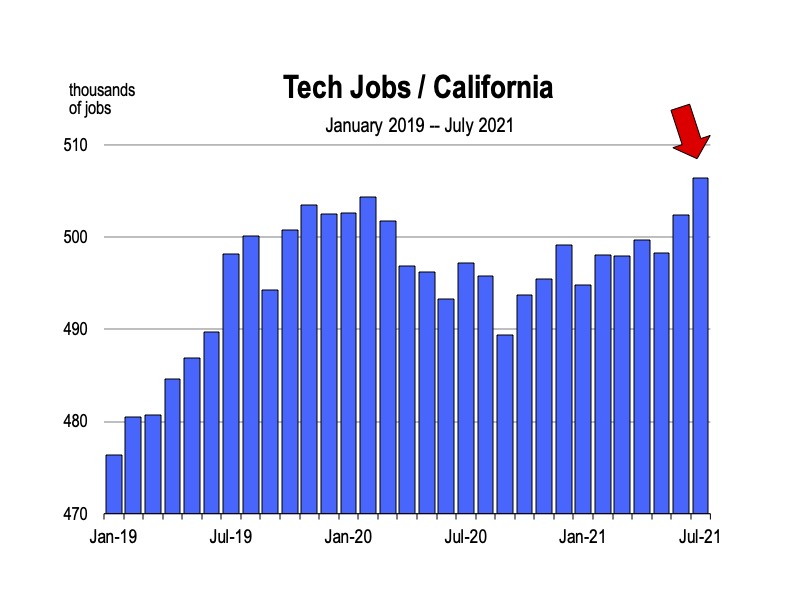

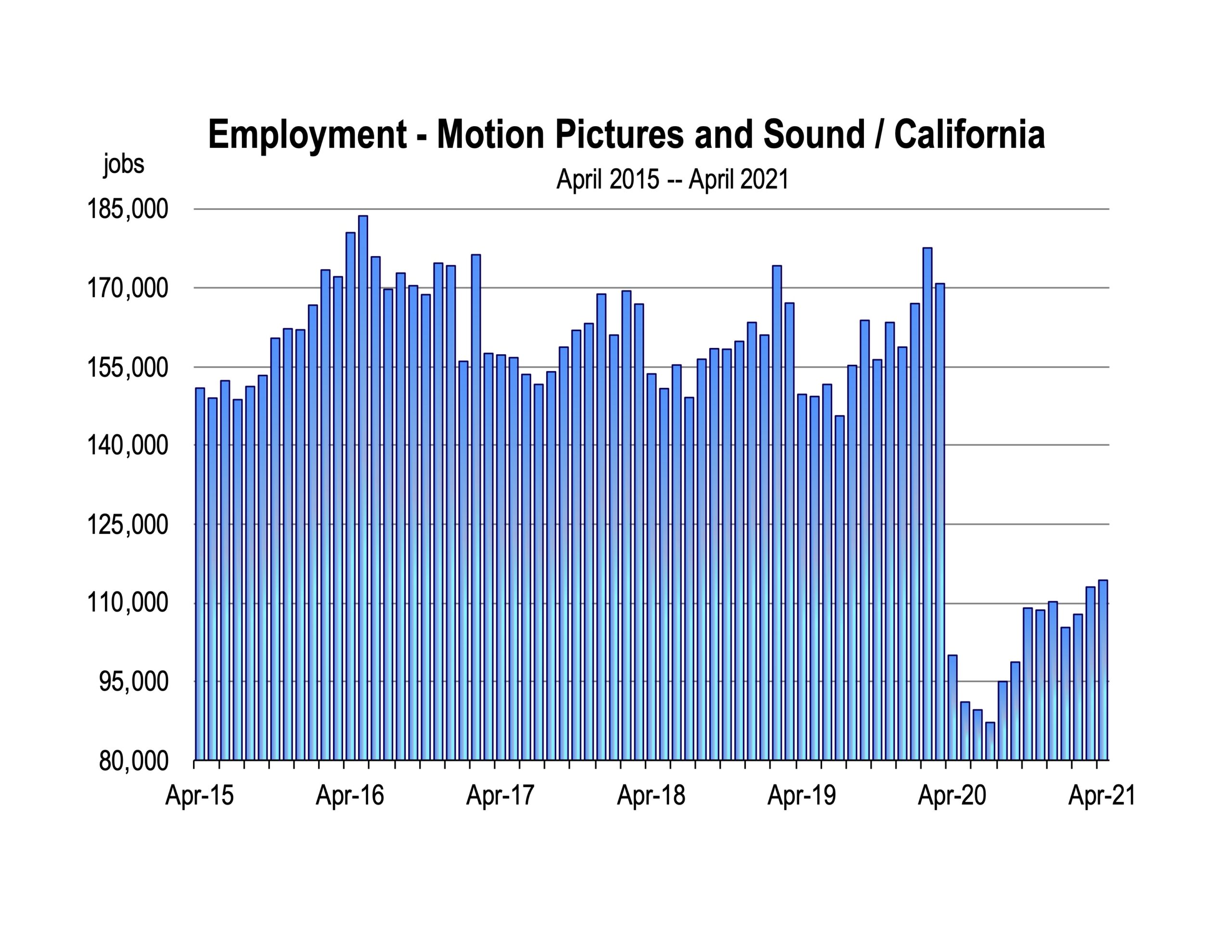

by Mark Schniepp The impact on the economy of California was more significant than the rest of the nation but the recovery will progress at a faster pace, catching up to the U.S. by 2023.

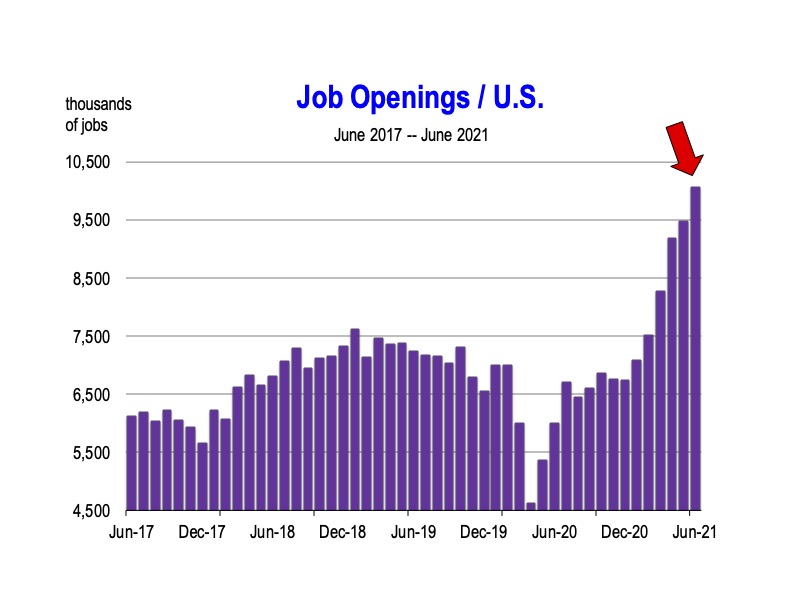

The impact on the economy of California was more significant than the rest of the nation but the recovery will progress at a faster pace, catching up to the U.S. by 2023. The Great Resignation

The Great Resignation Remote work and virtual meetings will continue

Remote work and virtual meetings will continue by Mark Schniepp

by Mark Schniepp

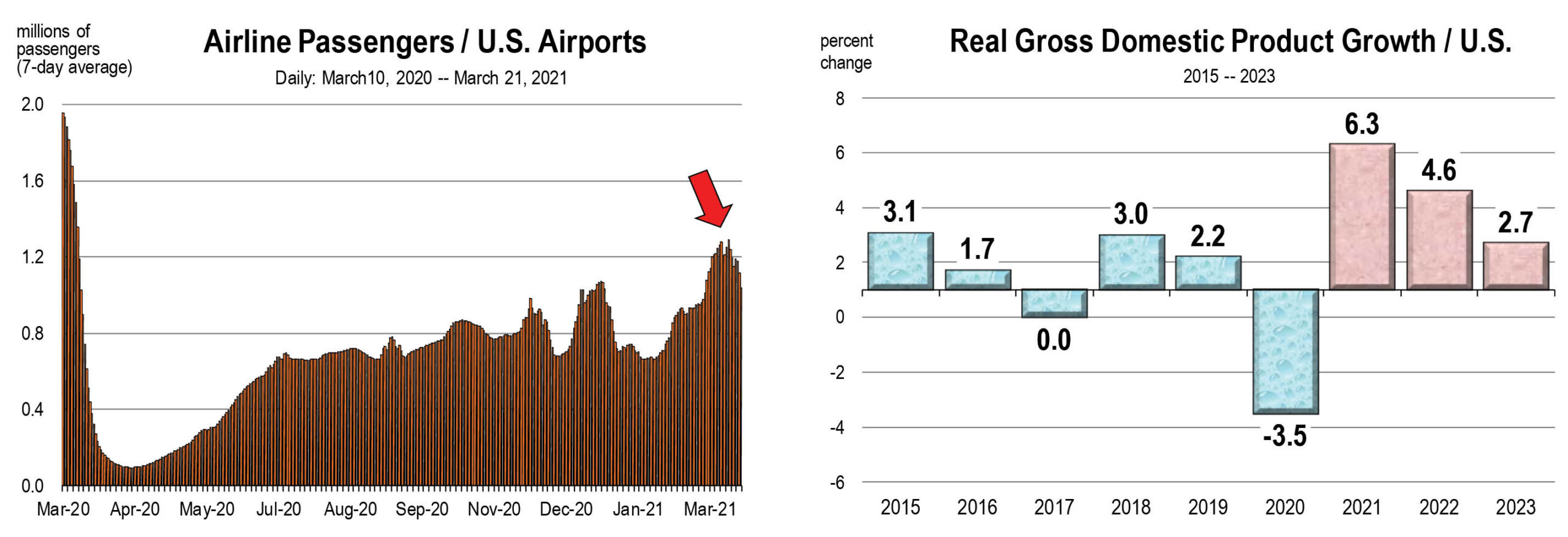

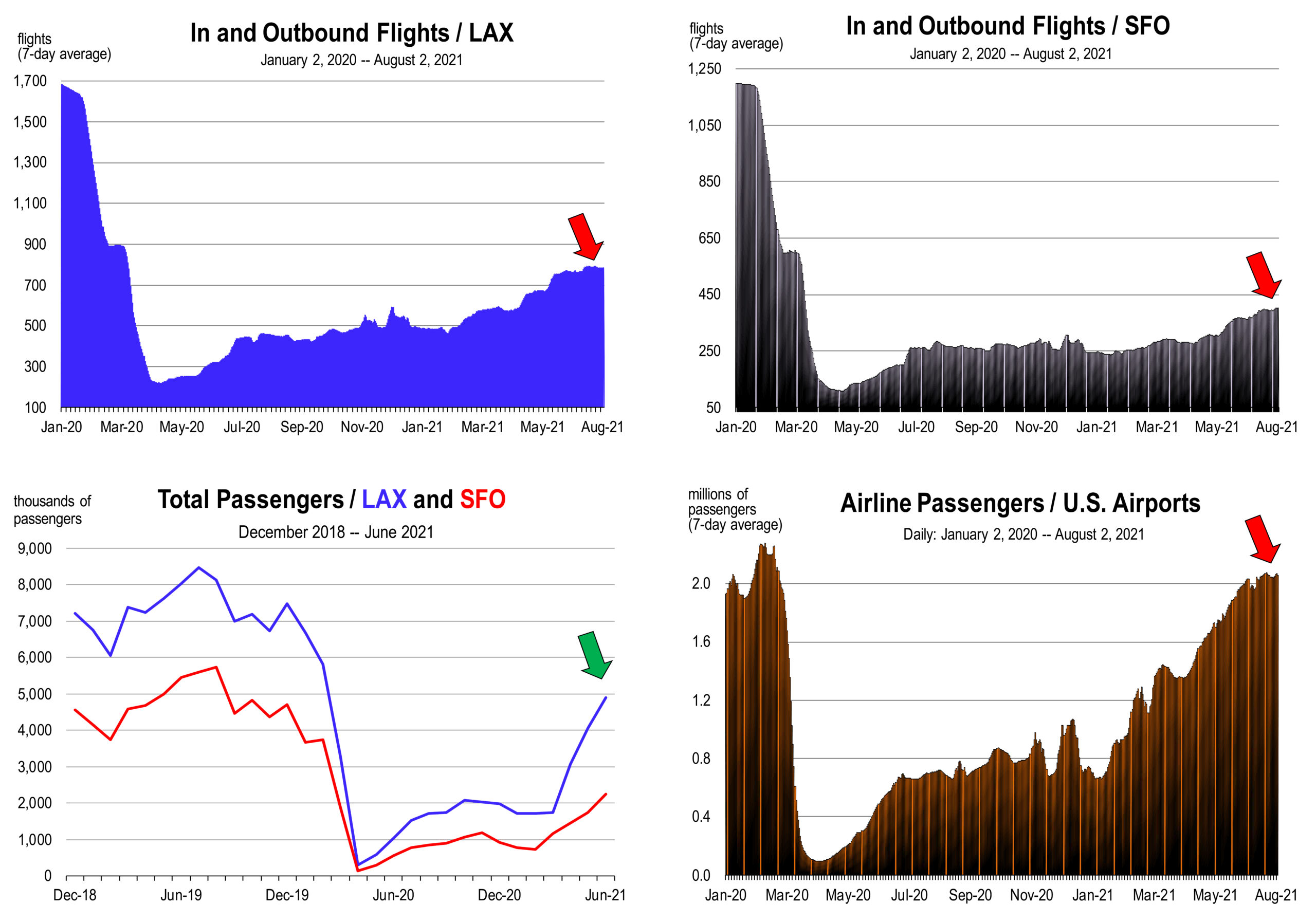

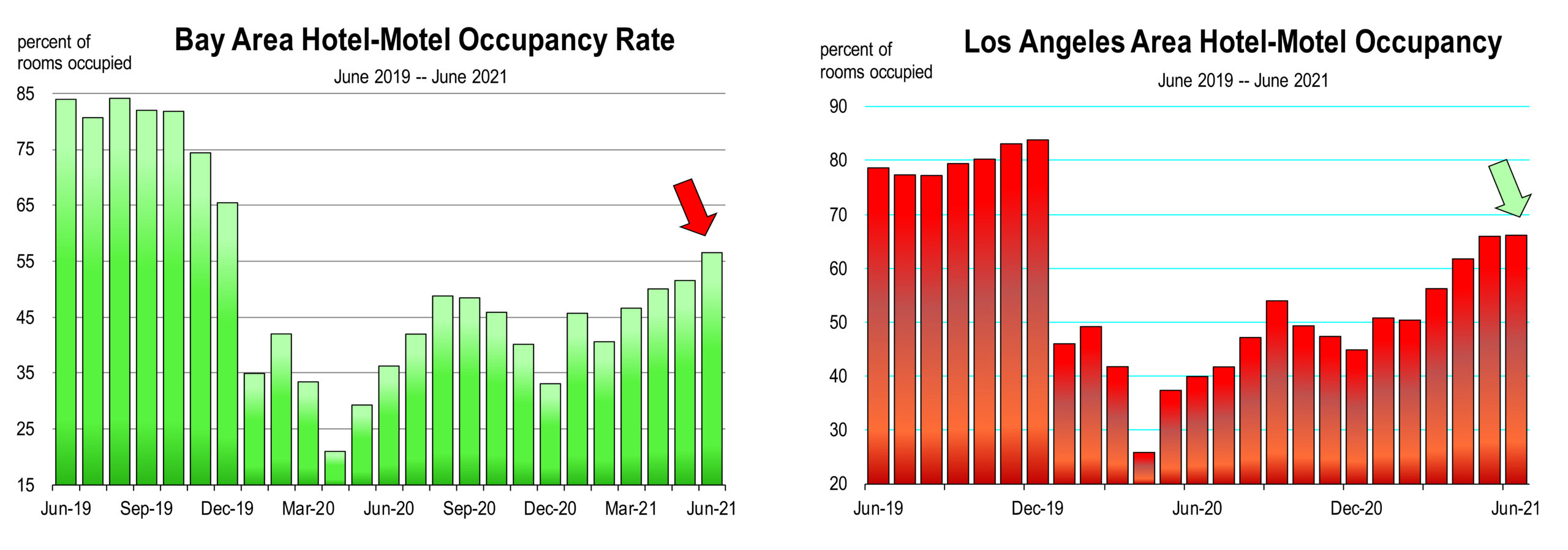

While air passenger travel in California has recovered 66 percent, passenger travel nationwide has recovered nearly 80 percent, and the clear increase in travel has produced higher hotel-motel occupancy rates.

While air passenger travel in California has recovered 66 percent, passenger travel nationwide has recovered nearly 80 percent, and the clear increase in travel has produced higher hotel-motel occupancy rates.

Travel related price increases are very likely catchup from the steeply discounted prices offered a year ago when no one was traveling anywhere.

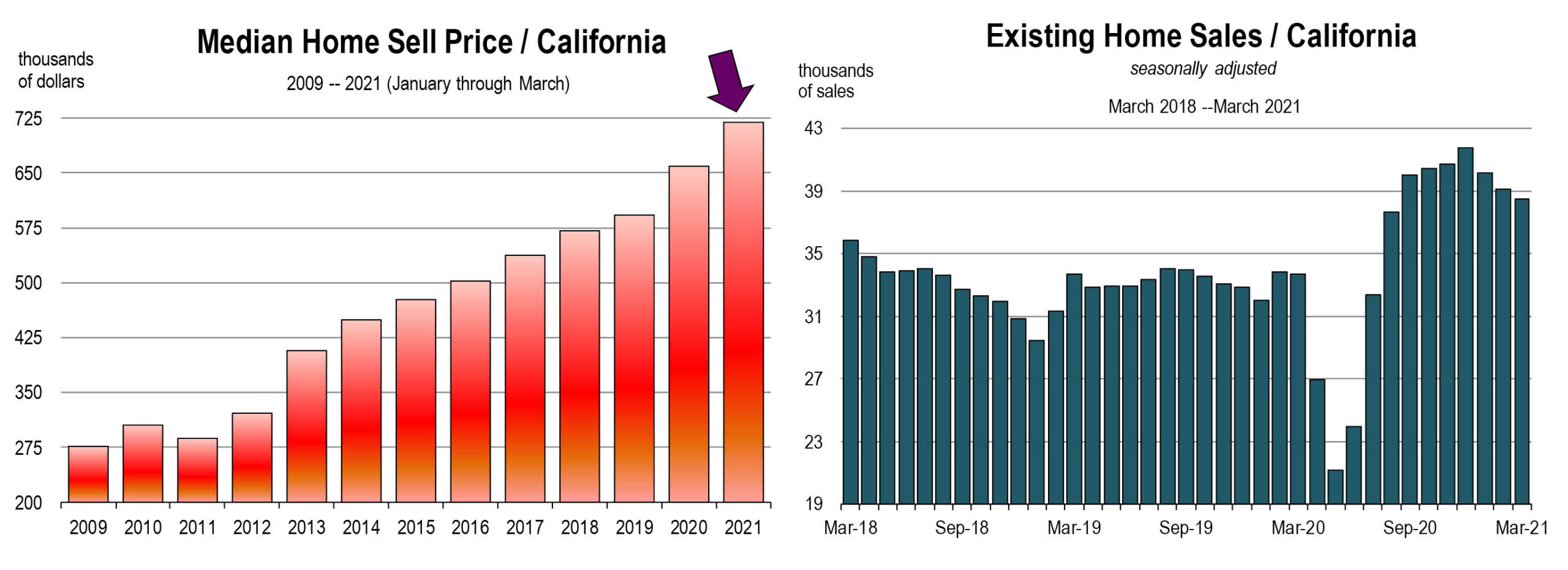

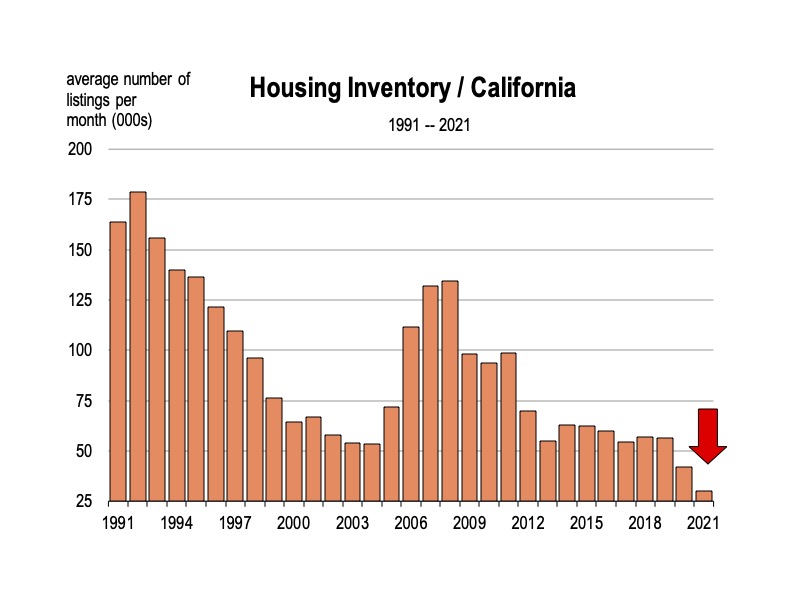

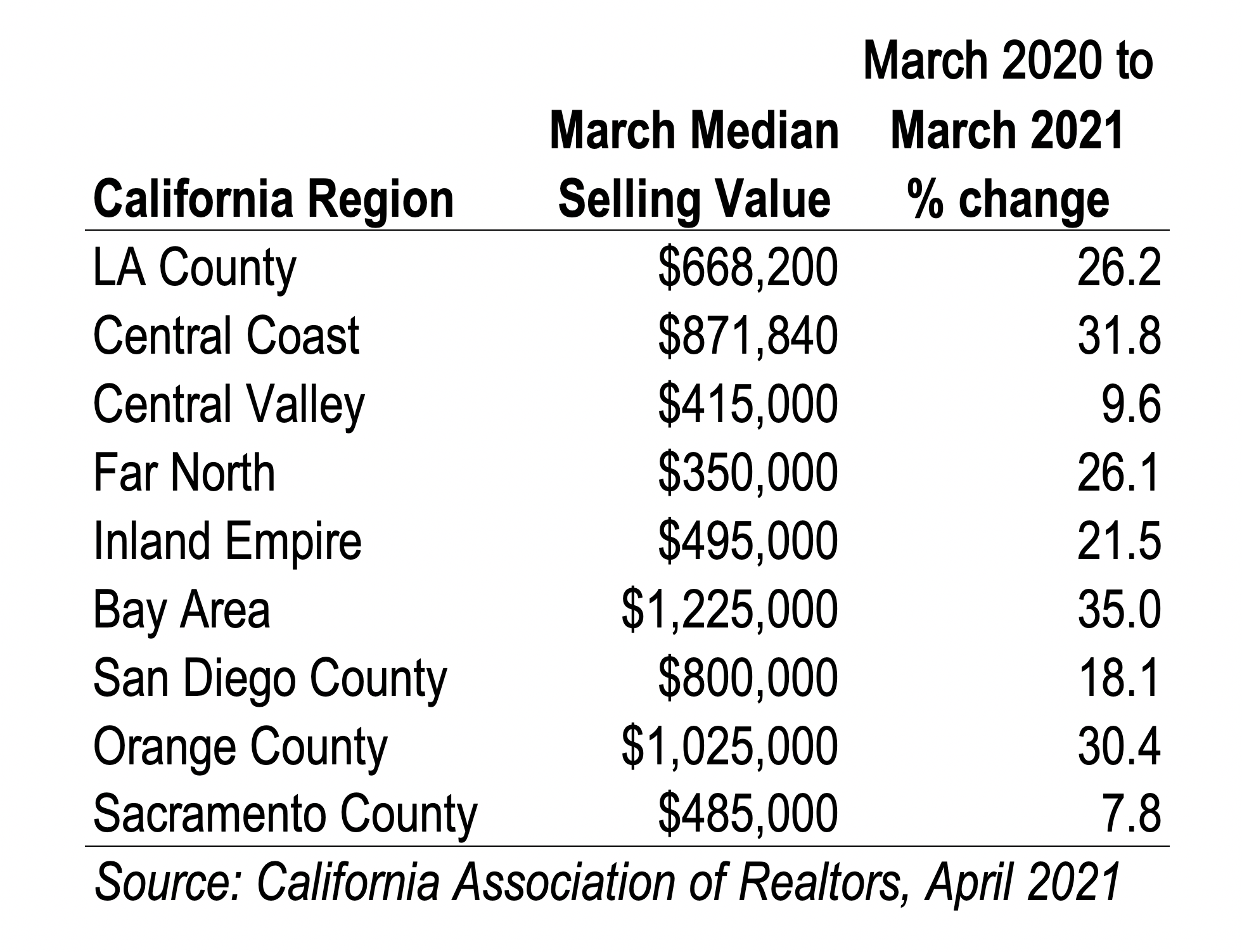

Travel related price increases are very likely catchup from the steeply discounted prices offered a year ago when no one was traveling anywhere. Only 1.16 million homes were on the market in April, a 20 percent drop from a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors. In California, over the last 6 months, inventory levels have declined to their lowest on record.

Only 1.16 million homes were on the market in April, a 20 percent drop from a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors. In California, over the last 6 months, inventory levels have declined to their lowest on record. What will be different?

What will be different? As the labor force rebounds, so will jobs in food services, hospitality and entertainment. As international travel resumes, larger gains are expected.

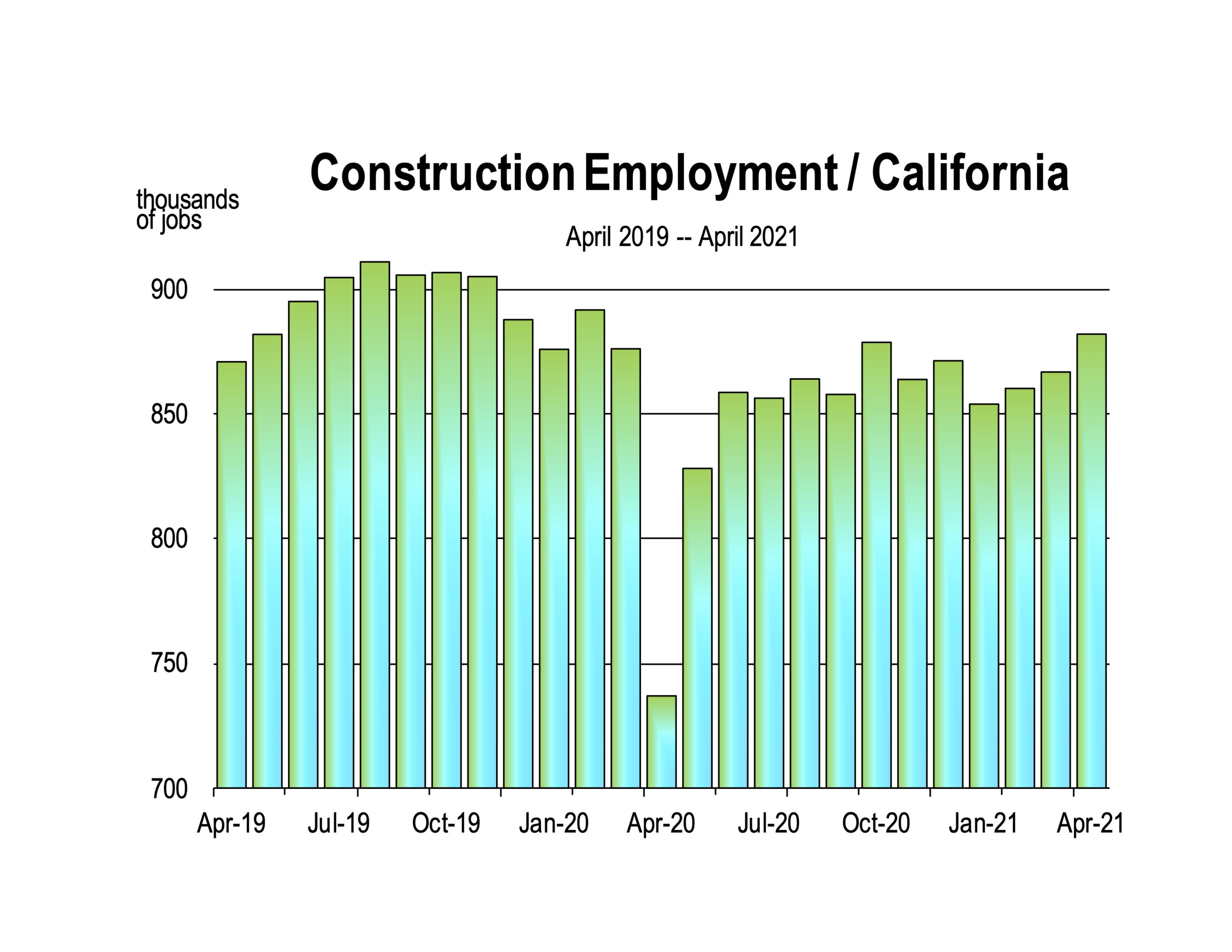

As the labor force rebounds, so will jobs in food services, hospitality and entertainment. As international travel resumes, larger gains are expected. New construction is underway all over Los Angeles, including LAX. The high-speed rail project continued through the pandemic and employs more workers now than at any other time. Large multi-family building projects have resumed in San Francisco and Sacramento. In downtown Los Angeles, they never stopped.

New construction is underway all over Los Angeles, including LAX. The high-speed rail project continued through the pandemic and employs more workers now than at any other time. Large multi-family building projects have resumed in San Francisco and Sacramento. In downtown Los Angeles, they never stopped. A return to normal

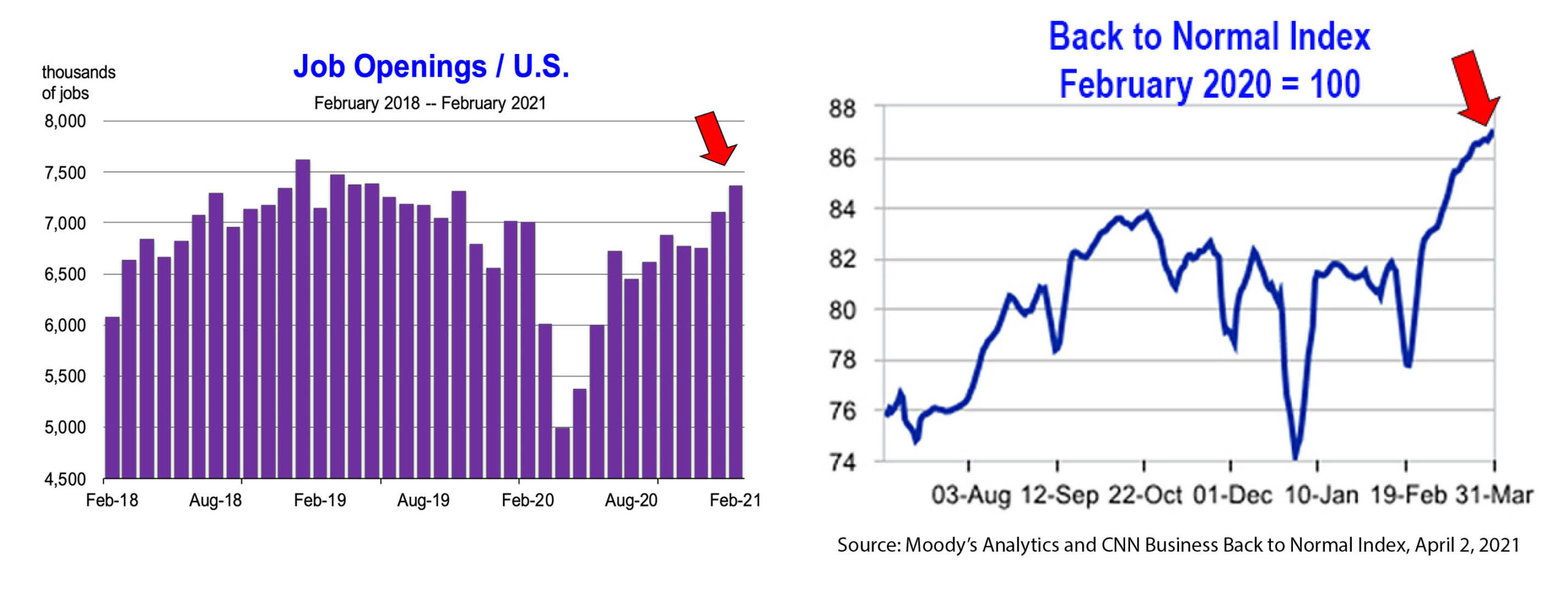

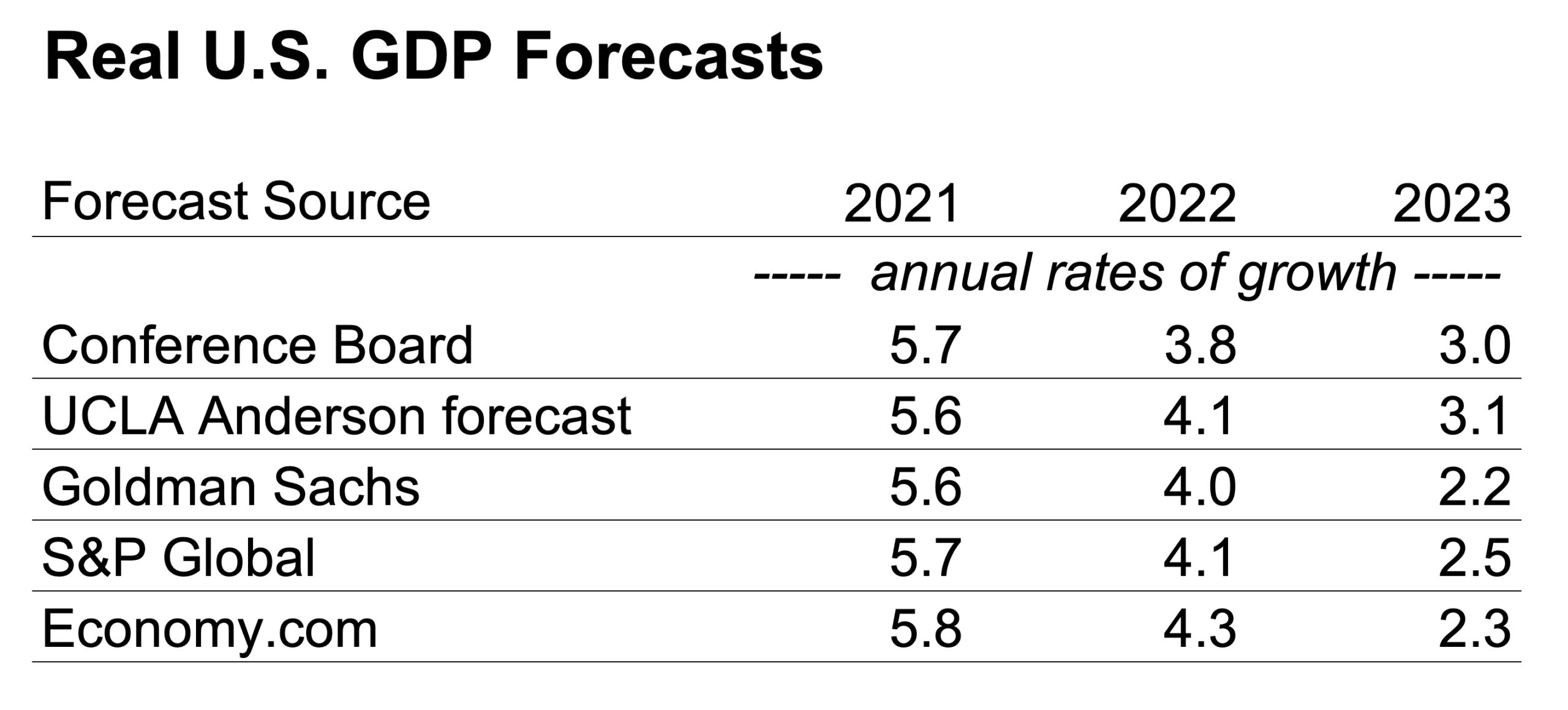

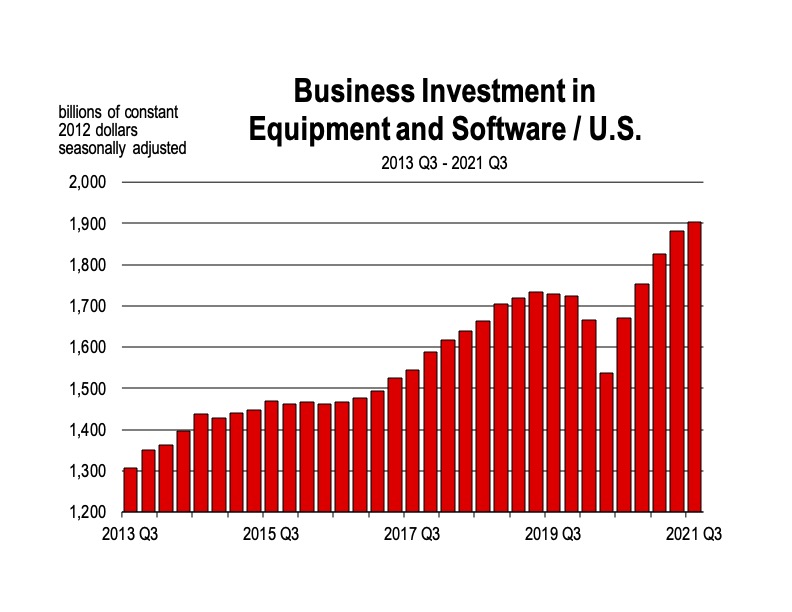

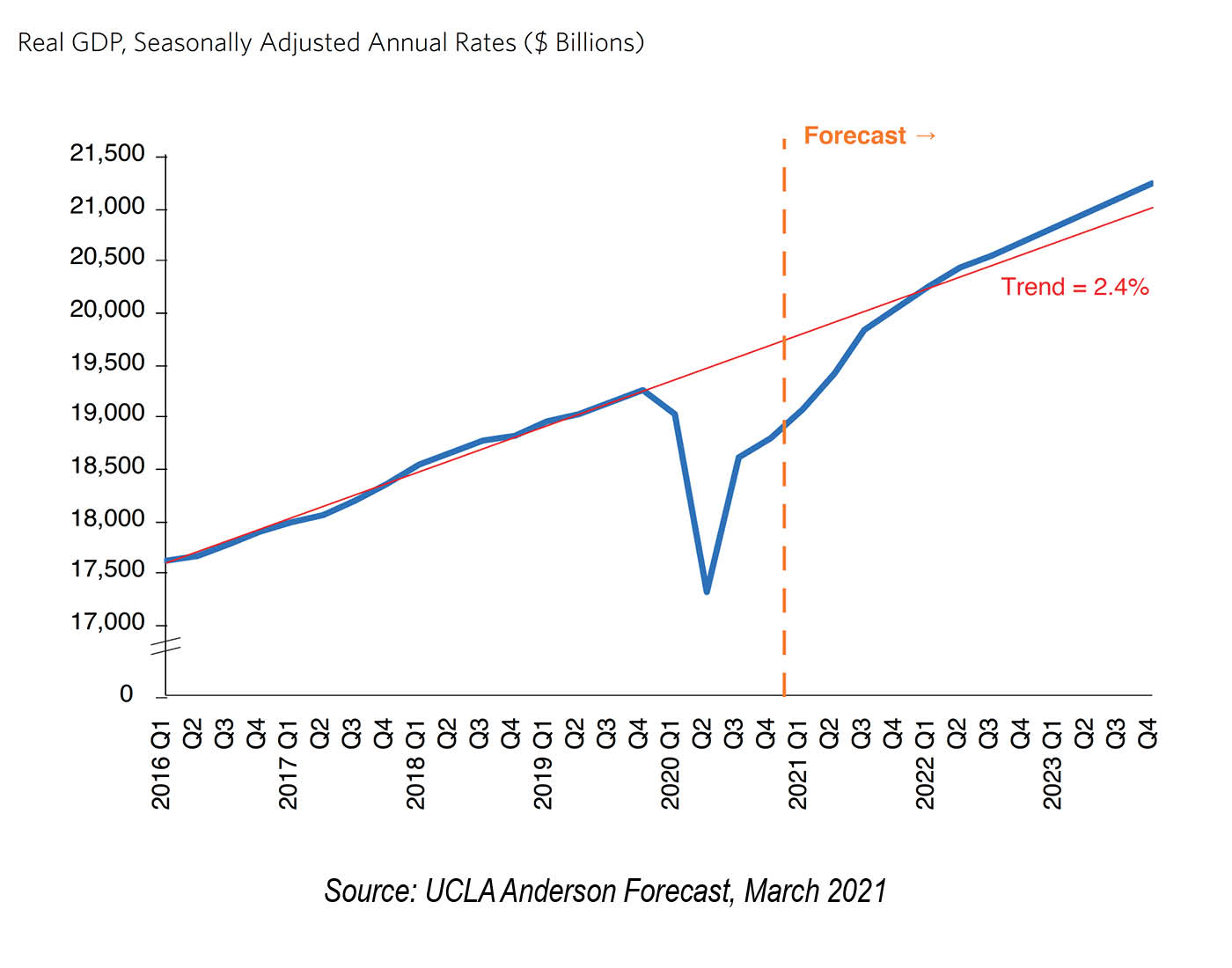

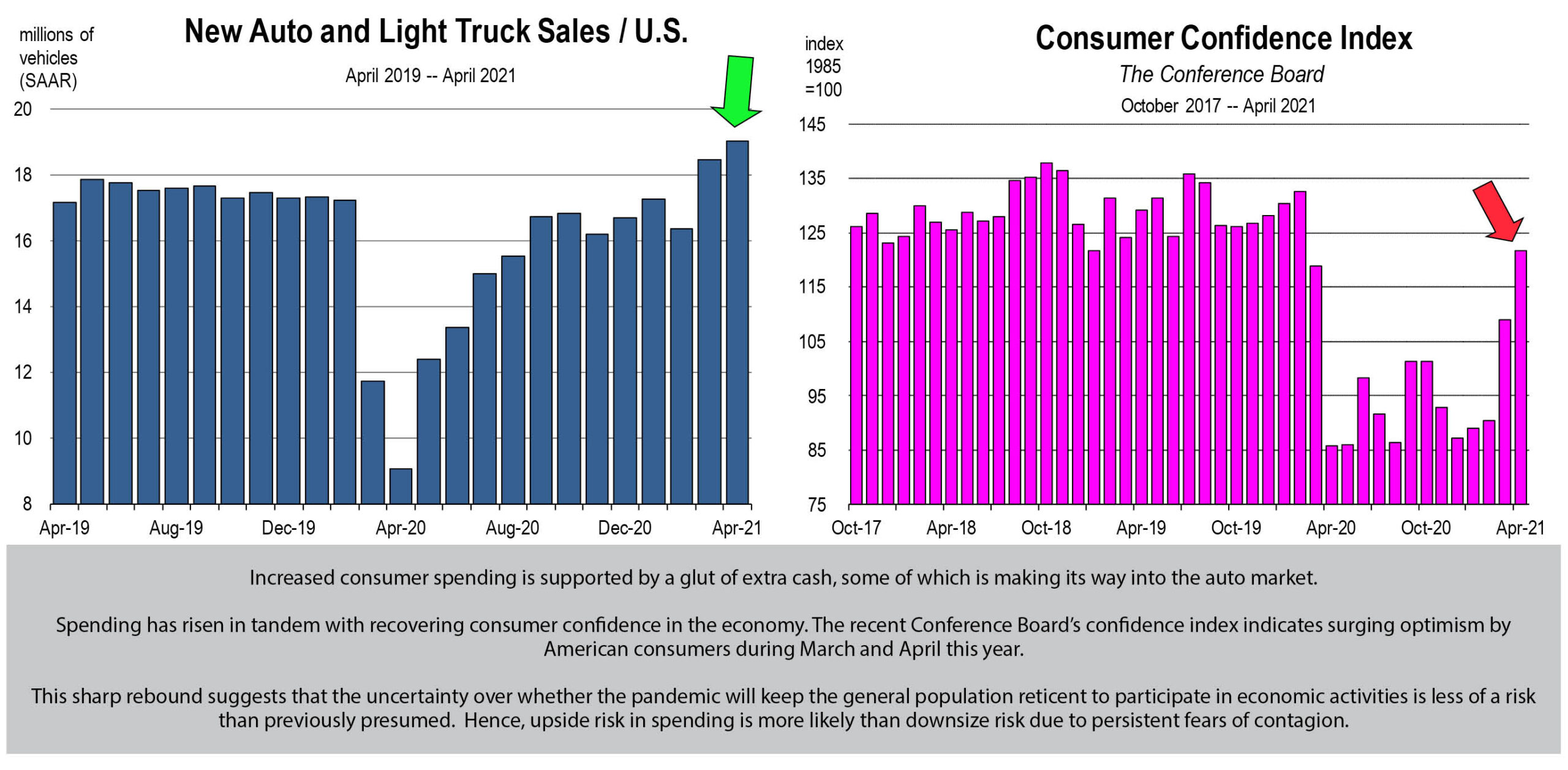

A return to normal Early spring and it’s all good news at this point. Though the improvement in the U.S. economy this year was expected, the actual levels of growth are better than anticipated.

Early spring and it’s all good news at this point. Though the improvement in the U.S. economy this year was expected, the actual levels of growth are better than anticipated.

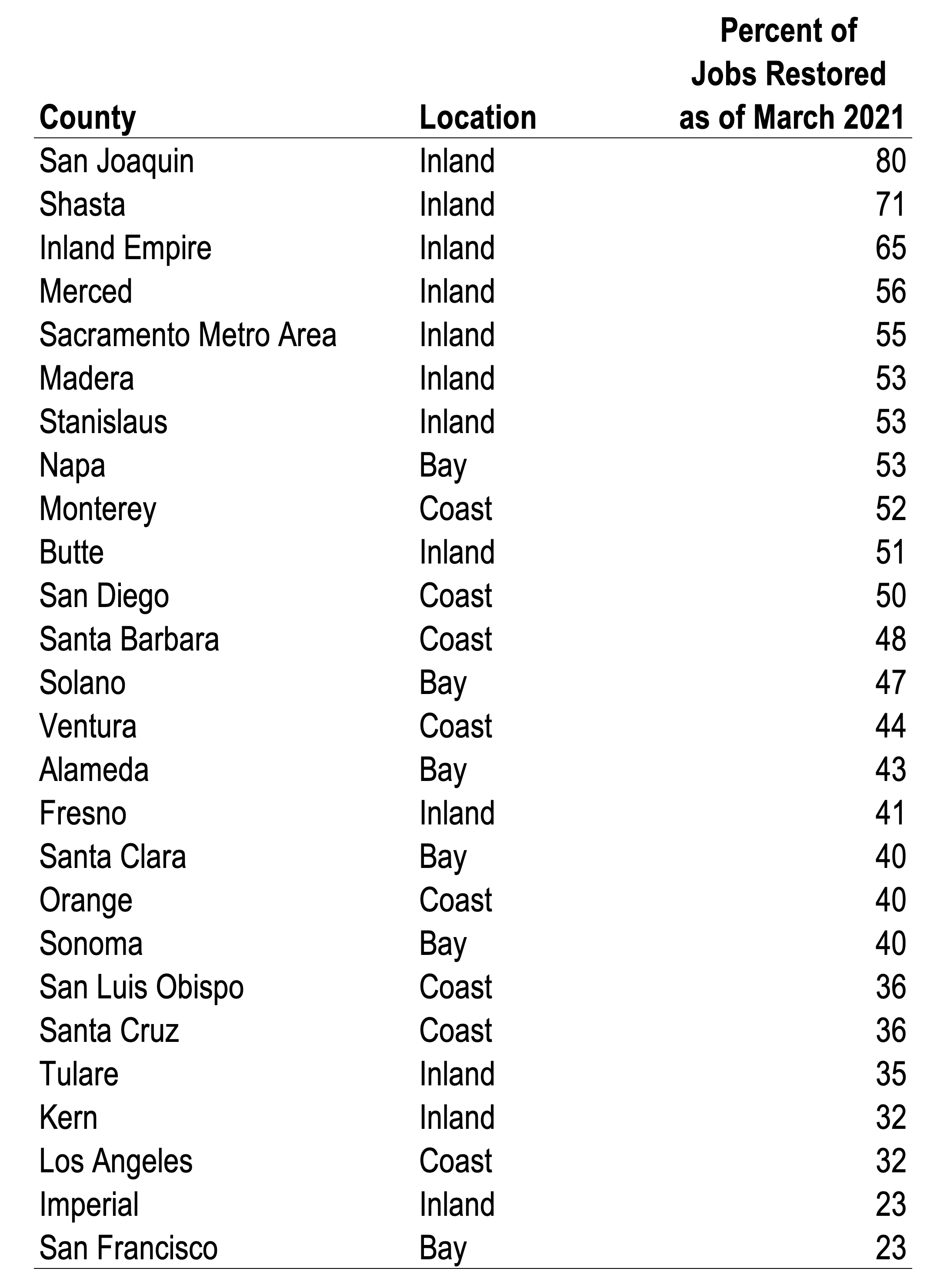

Through April 2021, the recovery is geographically uneven across the state, with inland counties reinstating their workforces faster than coastal counties or the Bay Area.

Through April 2021, the recovery is geographically uneven across the state, with inland counties reinstating their workforces faster than coastal counties or the Bay Area. We look forward to June

We look forward to June