By Mark Schniepp

April 5, 2022

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright,

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light;

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout,

But there is no joy in Mudville . . . .

— Ernest Lawrence Thayer, 1888

And as you know, the poem ends with Casey striking out, sending the crowd home unhappy.

The title of this newsletter was the title of a book by Stanford Economics Professor Tibor Scitovsky back in the 1970s. The premise of the book was that economic abundance does not necessarily lead to happy consumers.

The 70s was a decade of meager economic growth, high inflation, and a crummy stock market. There was no recession between 1975 and 1980 but it was nevertheless a joyless period for the economy.

April 2022

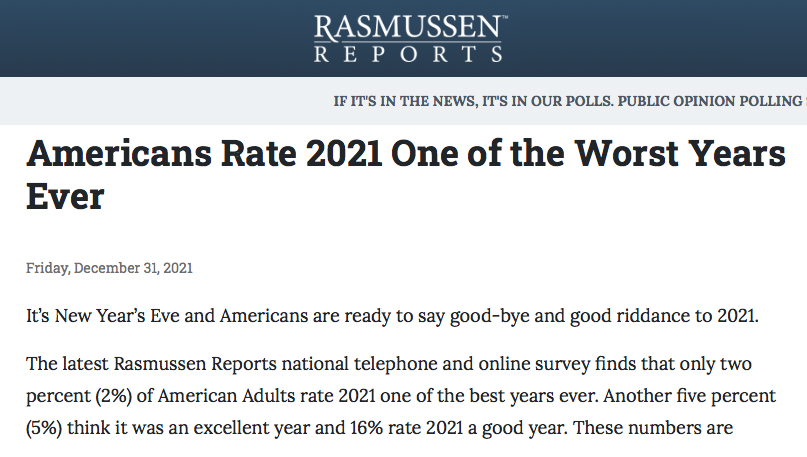

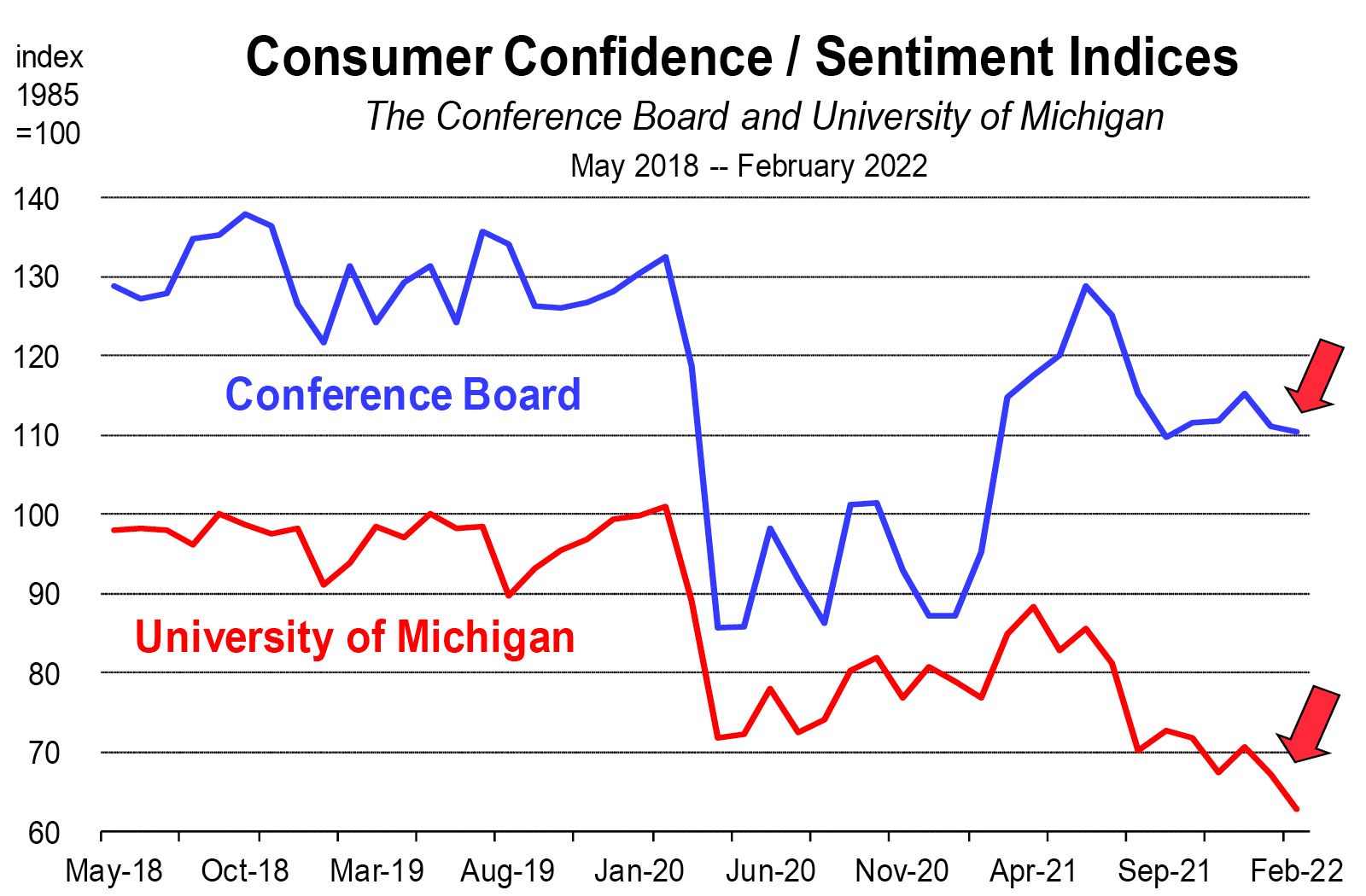

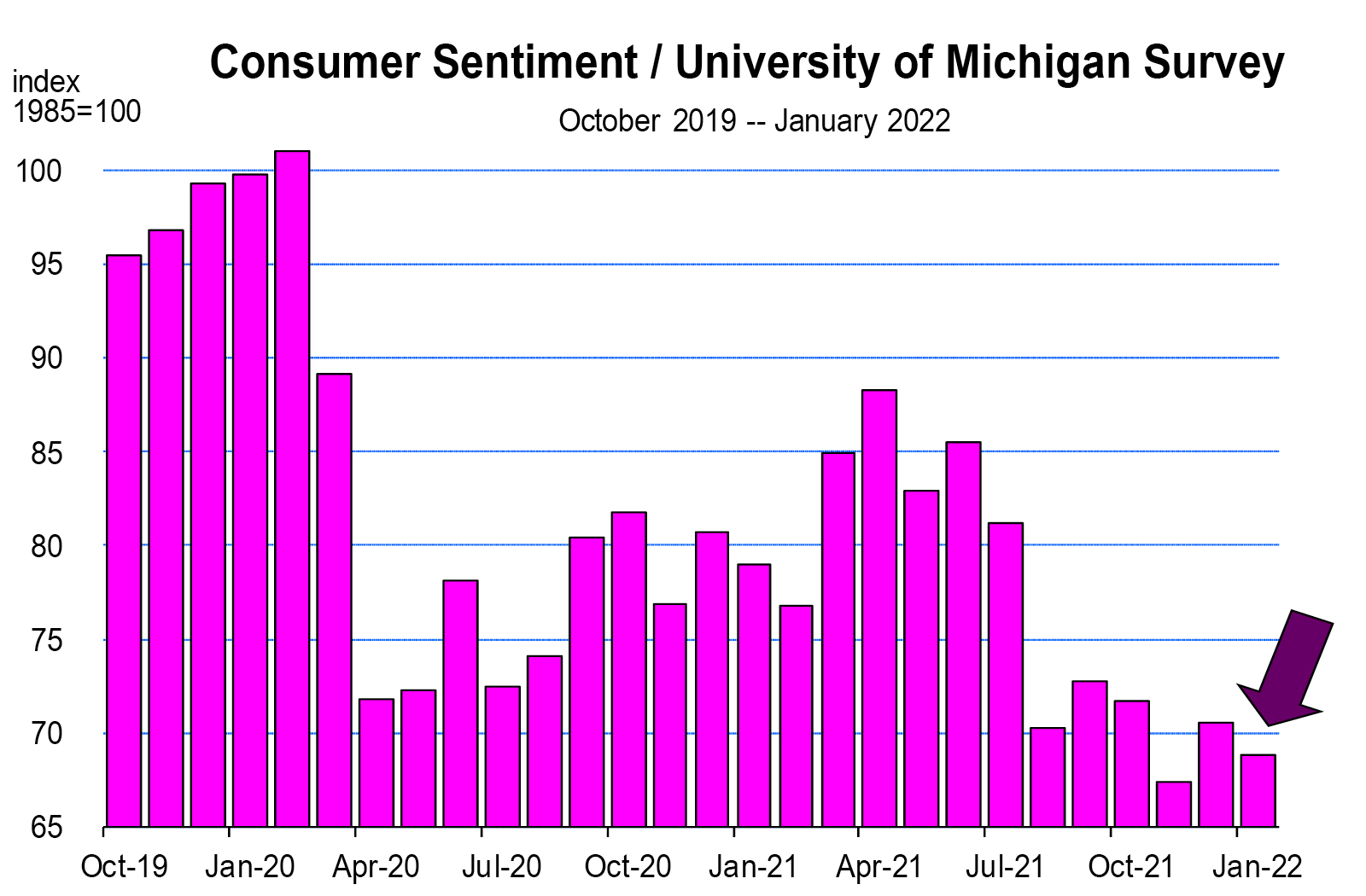

Today, a similar scenario has arguably emerged. Growth is stronger today than in the 70s, but there is a clear disconnect between economic growth and consumer sentiment—a relatively rare occurrence we have not experienced this century.

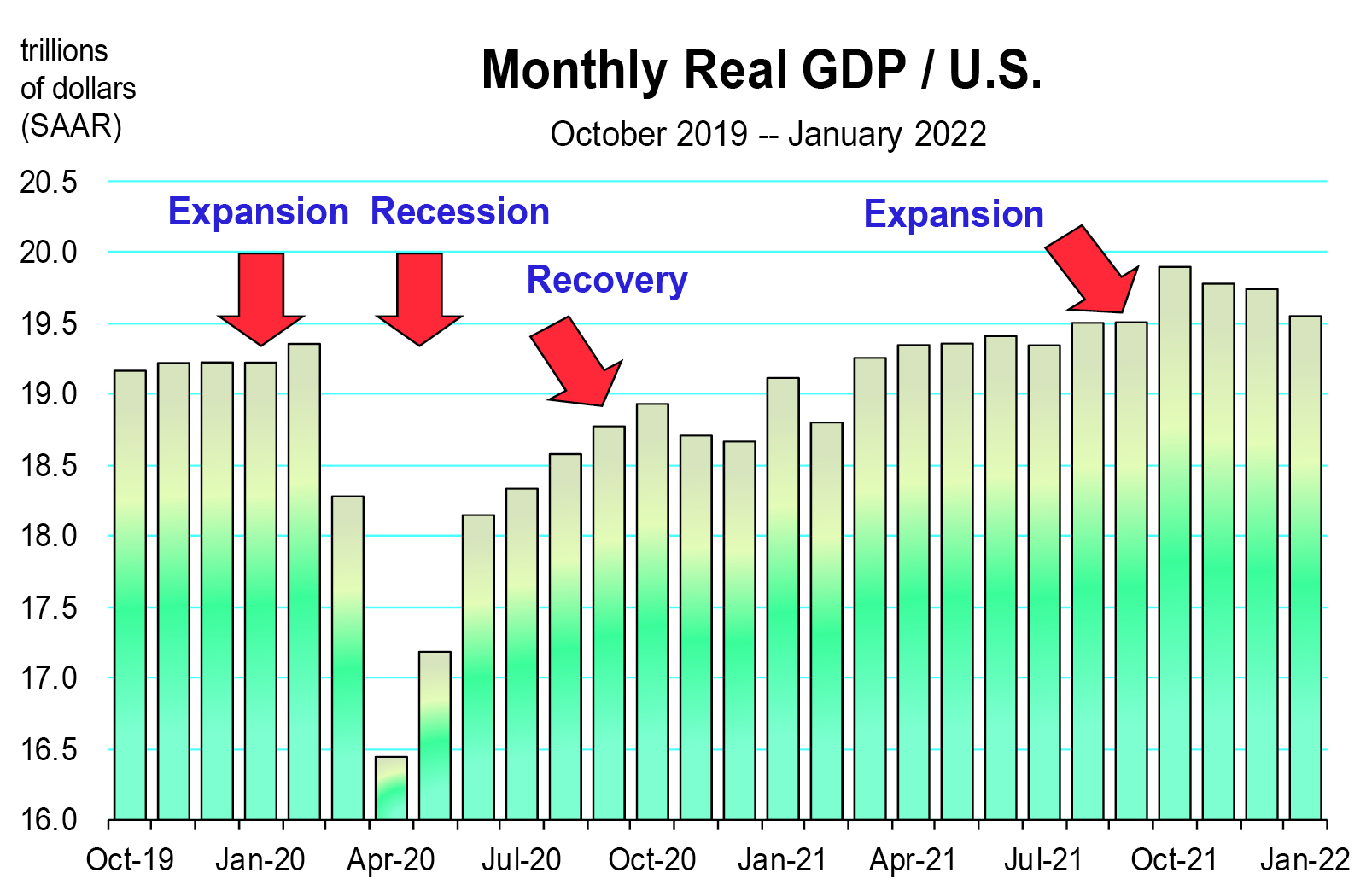

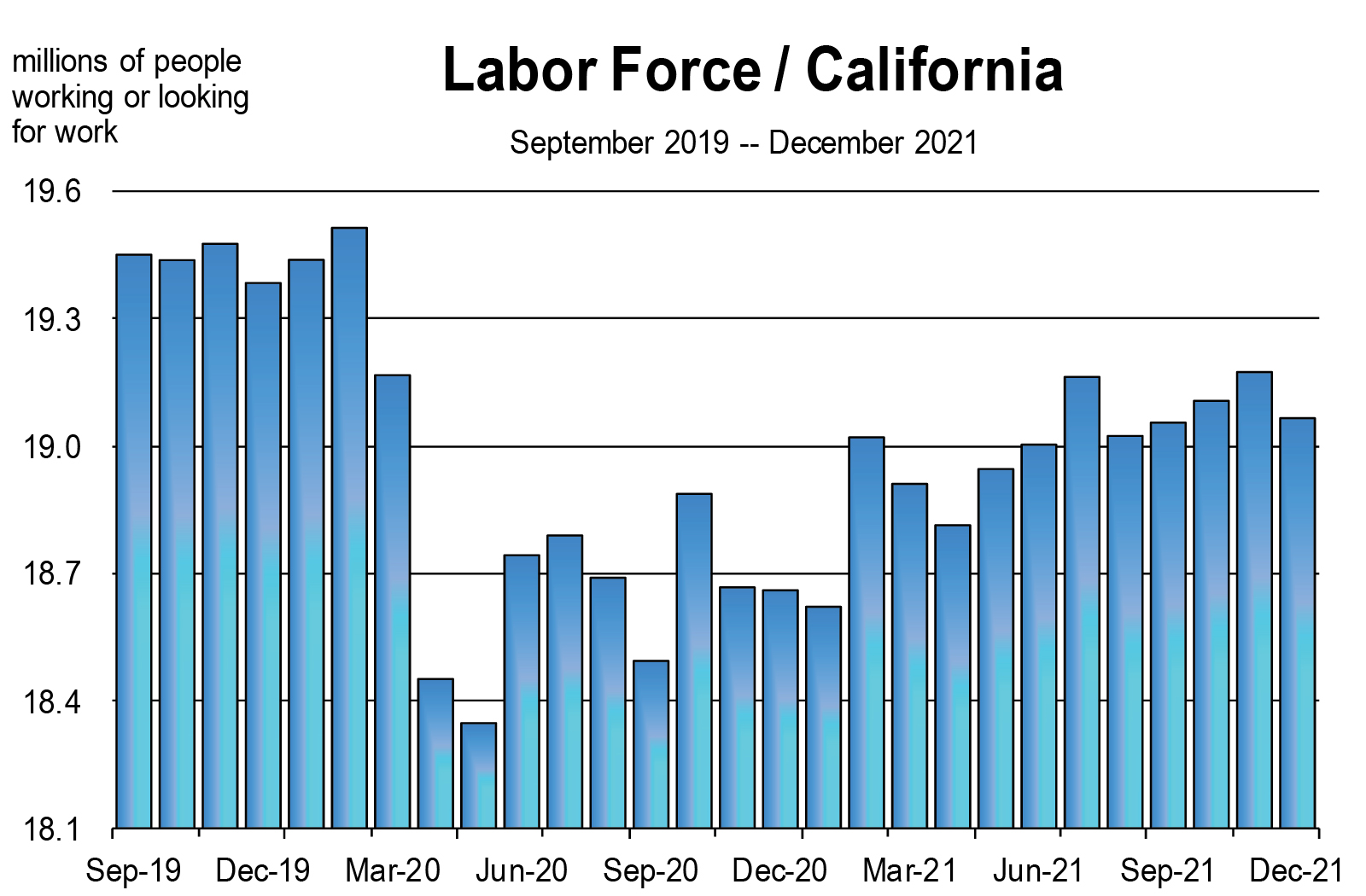

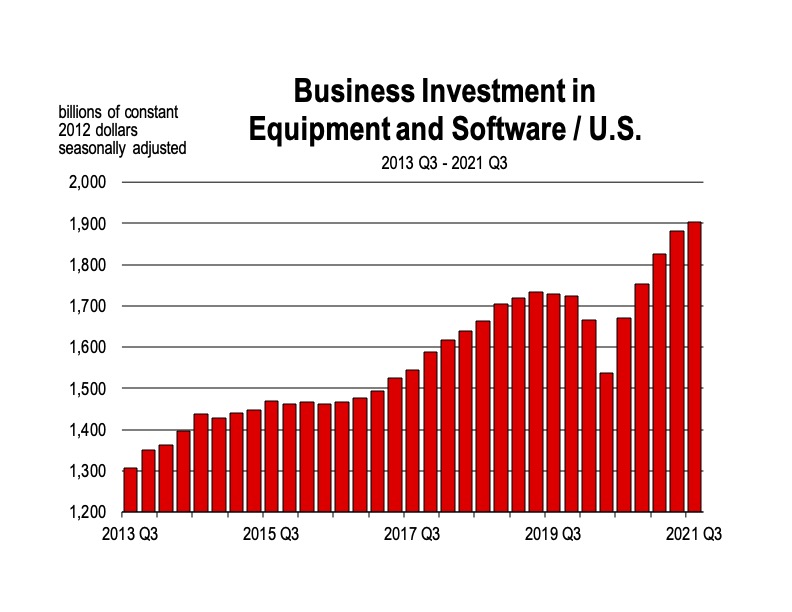

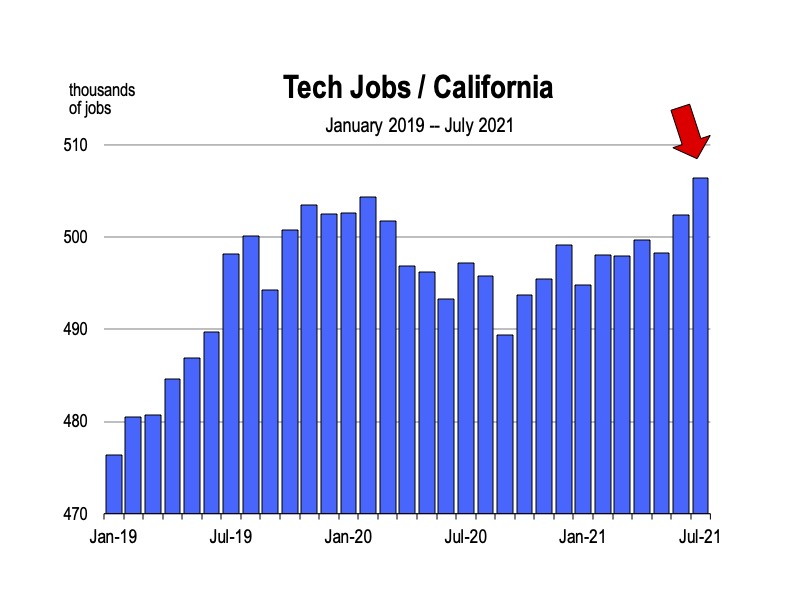

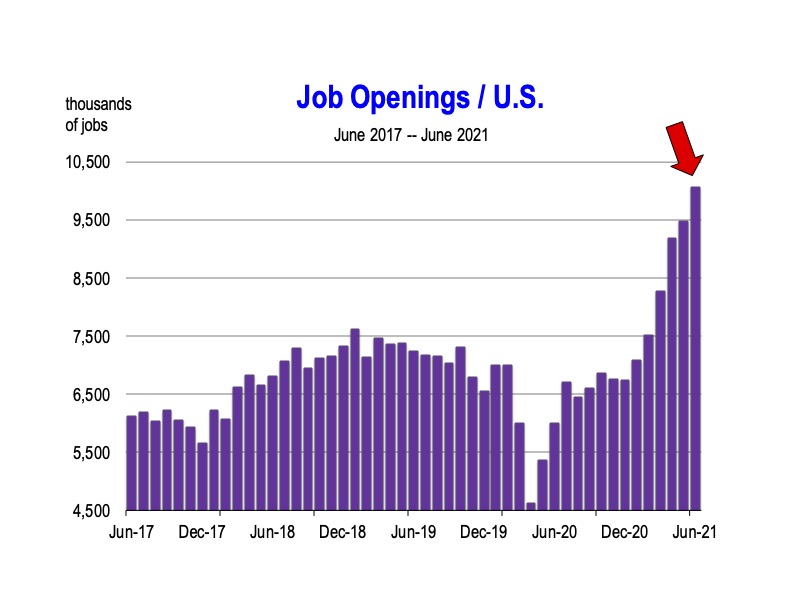

Economic growth was strong in 2021 and labor markets returned to their pre-pandemic status. If the economy is not at full employment, it is a heartbeat away from it. The labor market has tightened so much that job opportunities are not only abundant but go unfilled for many months.

The national economy has transitioned from recovery to expansion as we fly through the various phases of the business cycle.

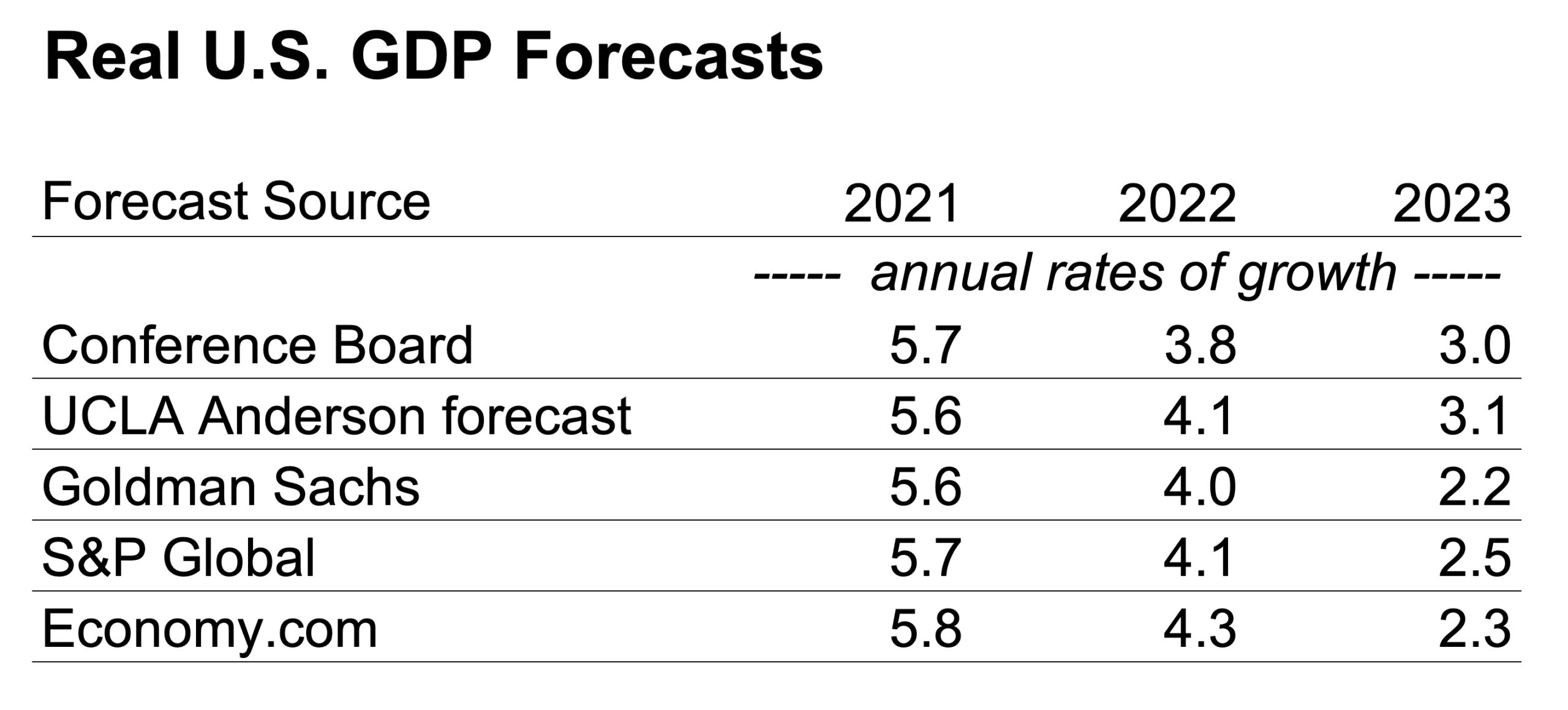

The markets for production and employment are healthy. The consensus forecast this year, notwithstanding the Russian-Ukraine war, is for a continuation of above long-term average growth, largely due to the final abatement of the pandemic, and the strength of consumer income including pent-up spending.

However, we are also in a period of economic turmoil. The inflation we are experiencing, coupled with the current geopolitical conflict, pose substantial downside risks to the economic outlook this year.

Surveys of business leaders regarding present business conditions and expectations of the economy’s performance through midyear are notably weak, with well over half of respondents feeling that present conditions are getting worse and will be worse later this year. The global economic recovery remains fragile.

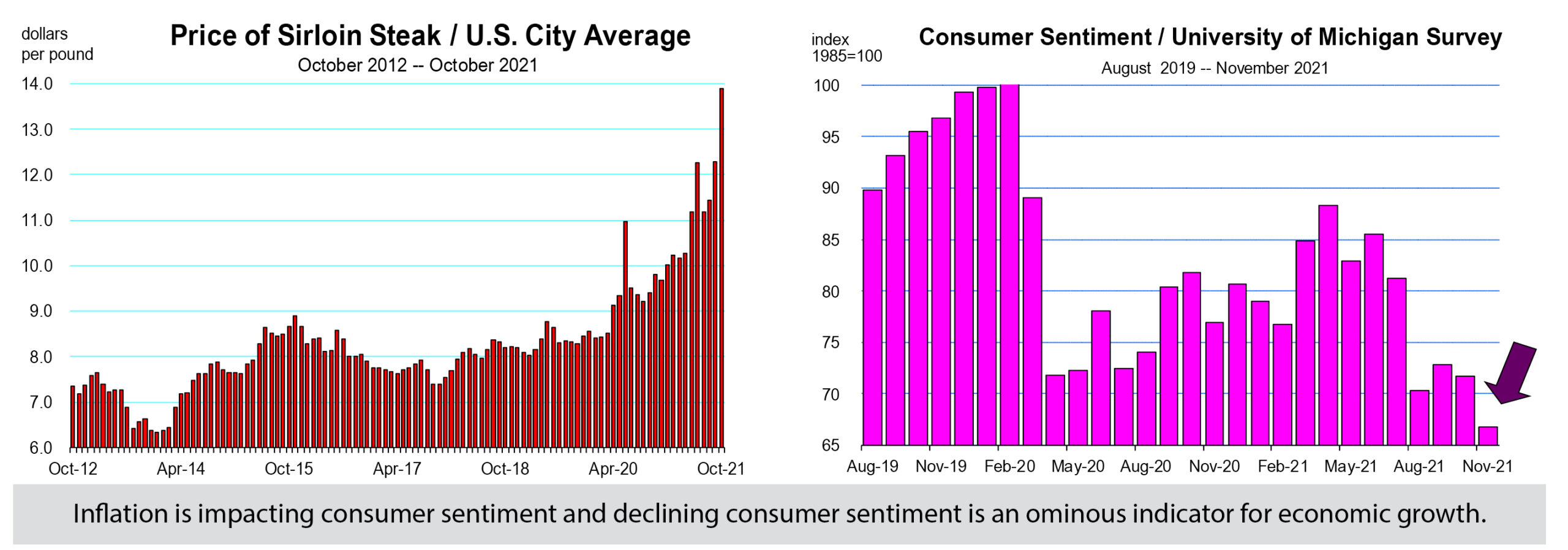

Consumers are decidedly more skeptical as measured by sentiment and confidence surveys conducted monthly.

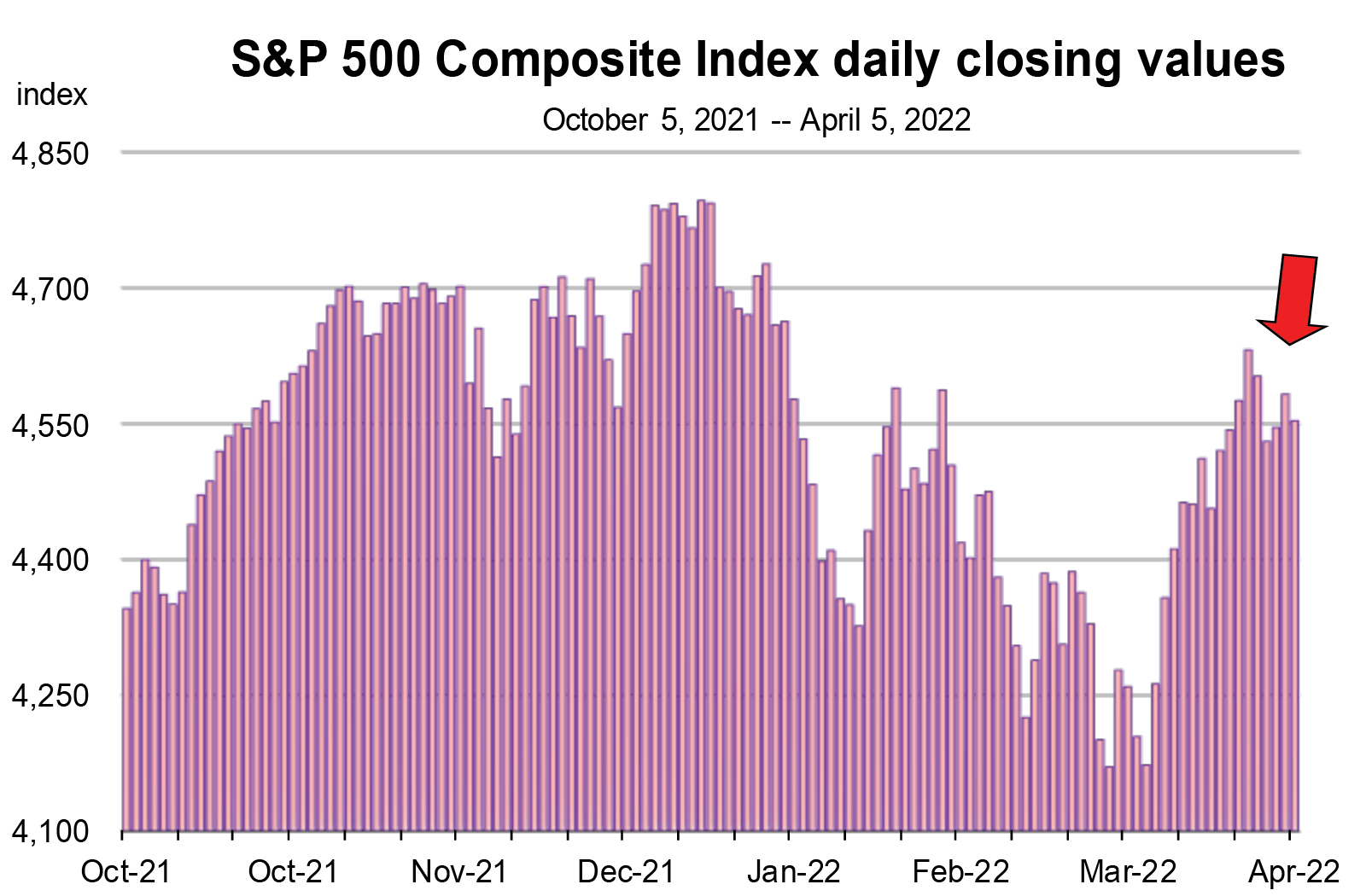

Certainly enough, economic growth has slowed way down in the first three months of the year to probably less than 1 percent. The Fed is on the verge of an aggressive monetary policy to interrupt inflation, planning a series of rate increases for the rest of the year and ending the asset purchase program. The stock market has been understandably in flux.

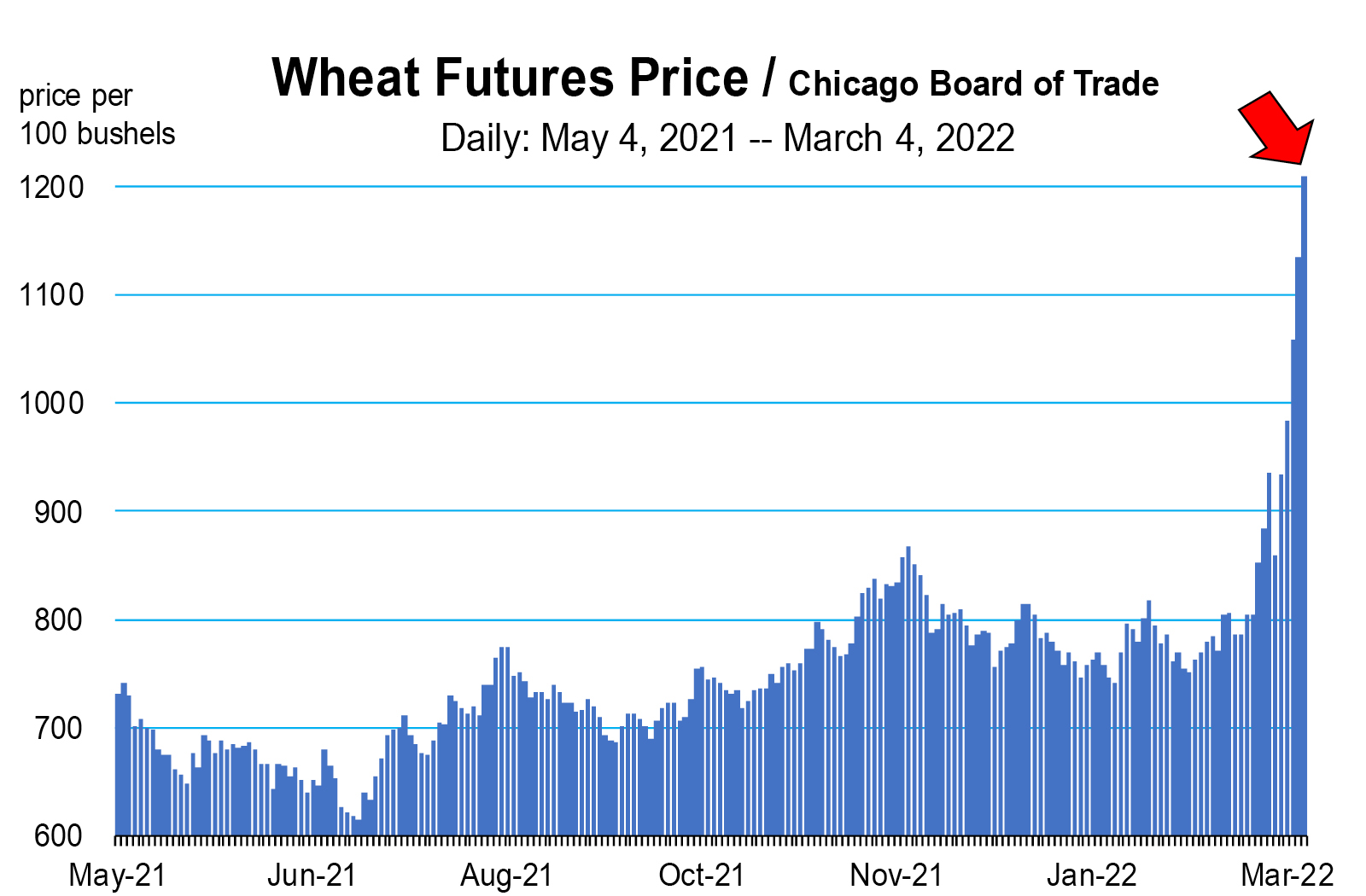

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global response create an escalating uncertainty that is not good for the world economy. Sudden higher oil, natural gas, agricultural and metal prices are conflating with already painfully high inflation caused by pandemic disruptions to supply chains and labor markets.

The U.S. economy should be largely insulated from the war unless a more aggressive policy direction is taken, or if Russia responds to U.S. imposed sanctions with cyberattacks on U.S. energy infrastructure.

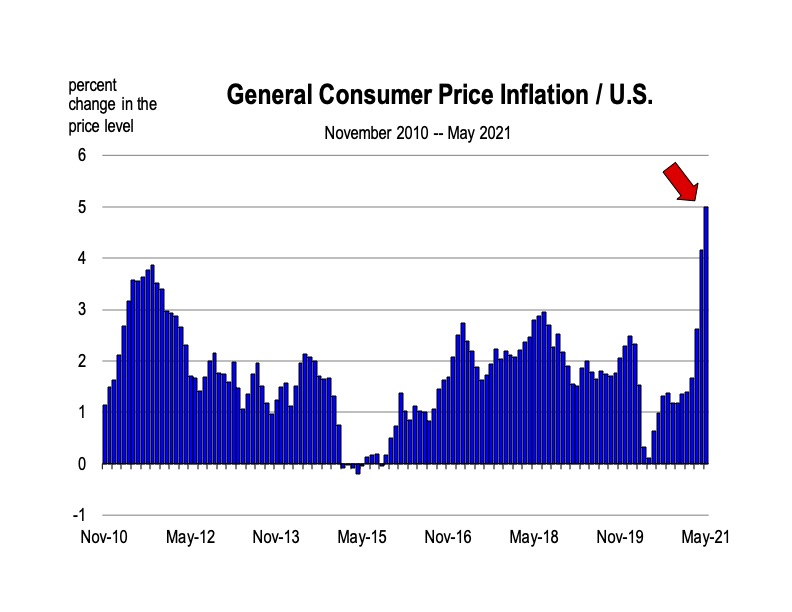

Accelerating Inflation is now the largest risk, and the current level of inflation (already at a 40 year high) predated the Russian-Ukraine war. This was the biggest concern of Americans in the March poll by Gallop.1 An end of the war will not cure inflation, nor is it likely to reverse the current stock market consolidation that is also of worry to consumers.

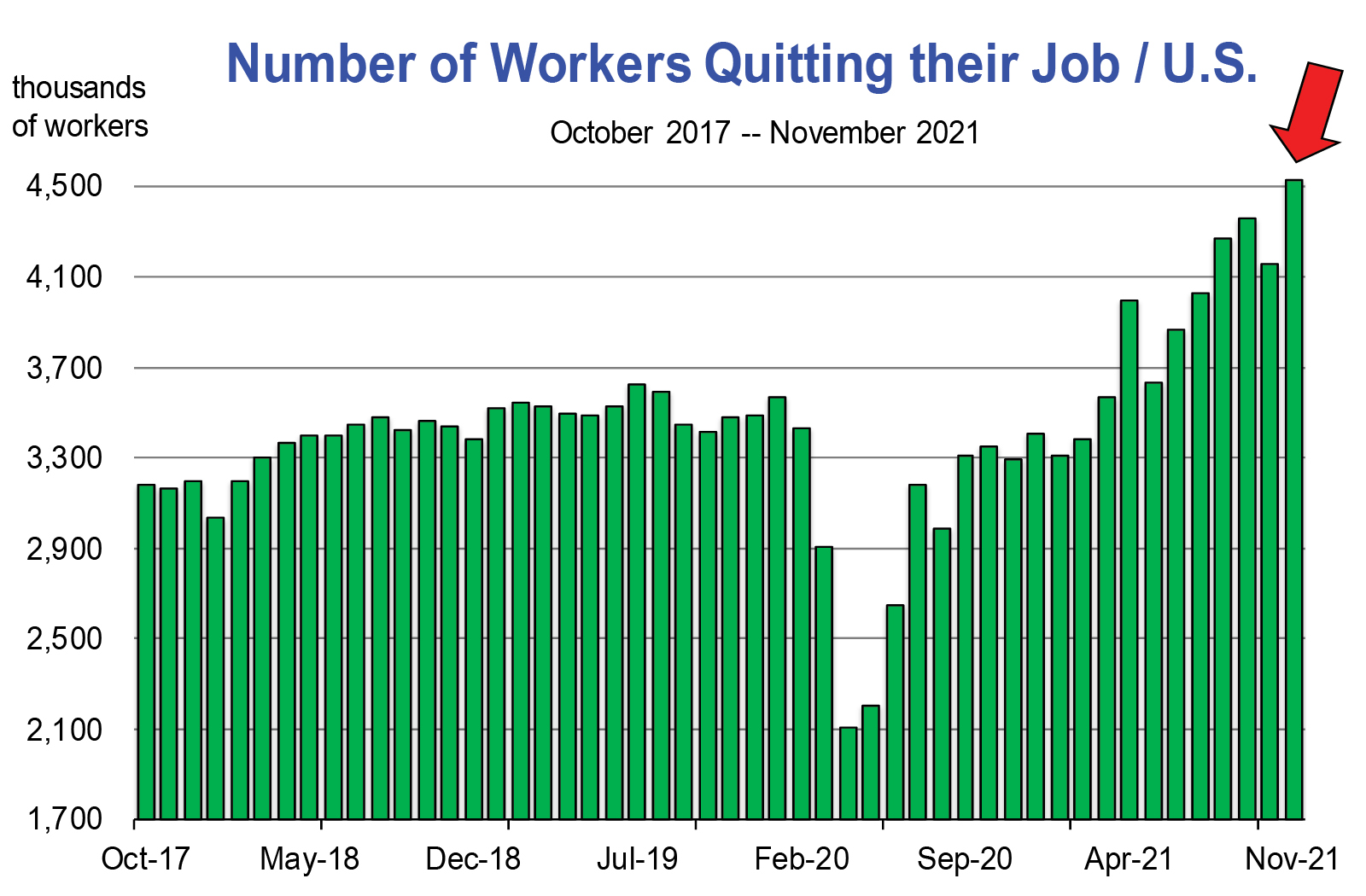

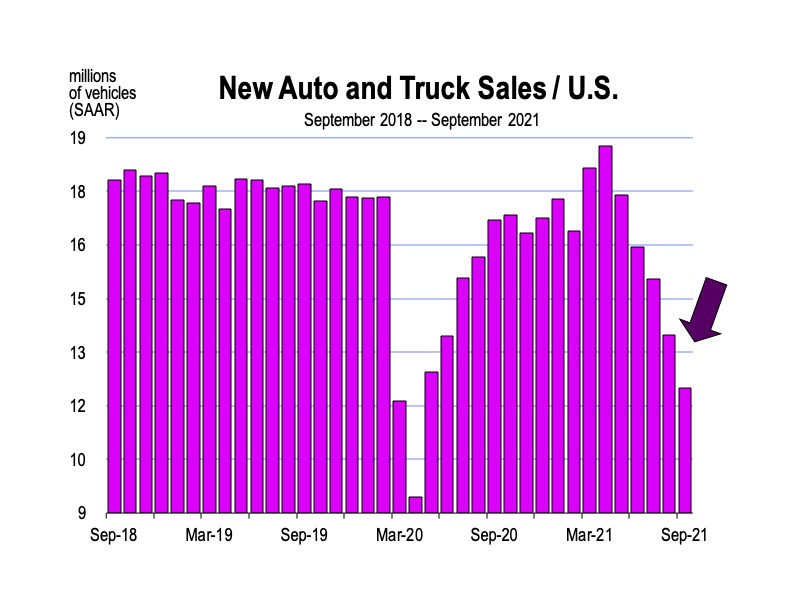

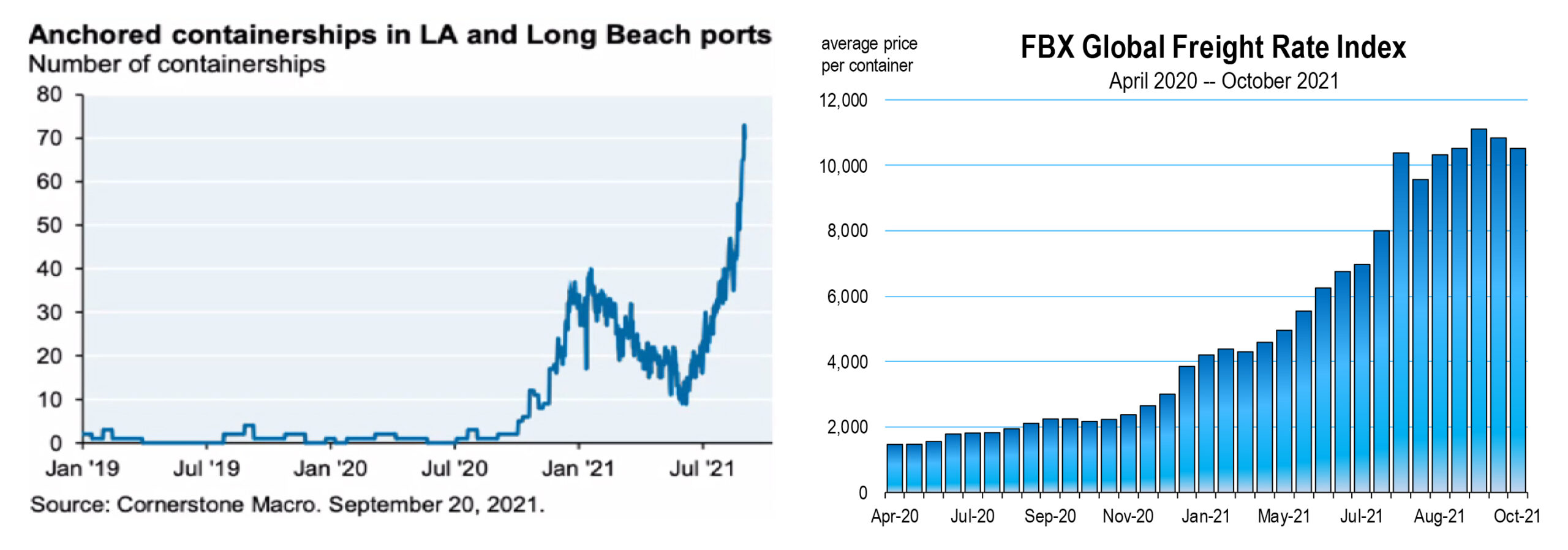

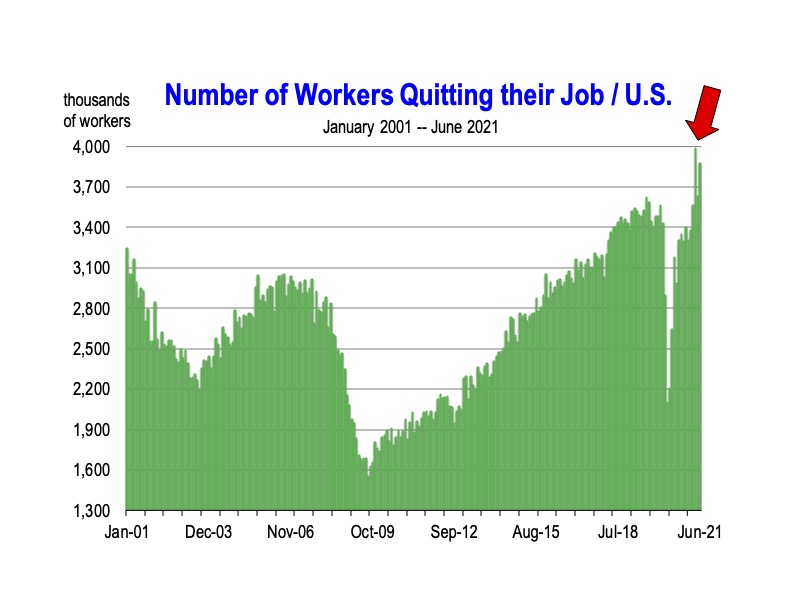

The supply chain problems have been severe. The rising job openings have been severe. The lack of products and workers has driven prices and wages sharply higher.

So right now, amidst all the problems which appear to be weighing heavy on our sentiment in grocery stores and at gas stations, and putting aside the 2 month pandemic recession, this is clearly not our happiest of moments.

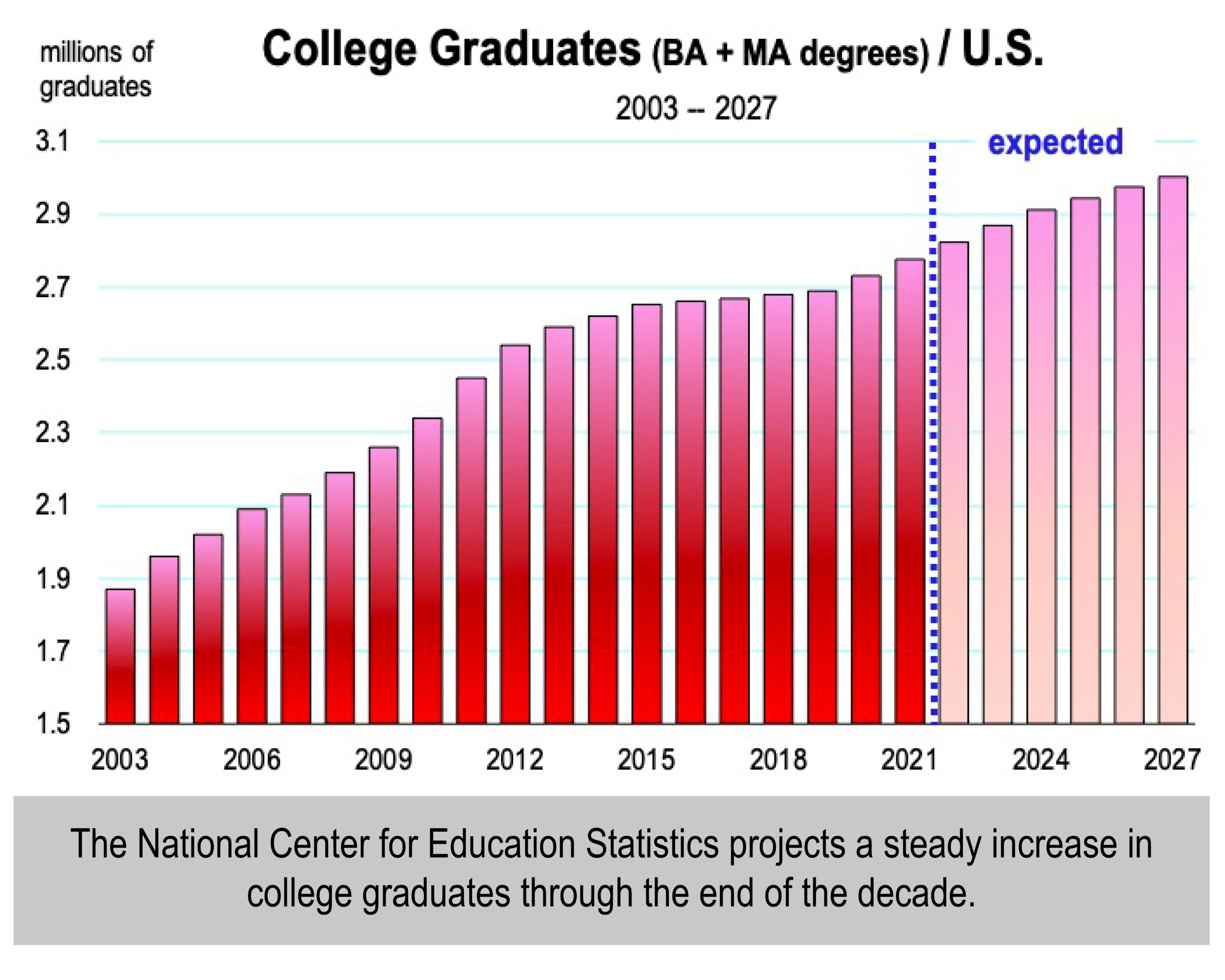

But other than crude oil, production of goods will come back. So think about all the production that will occur to replenish needed inventories that are in steady demand. And the labor force should also return with pandemic related reasons now dissipating. The unemployment rate could increase more than the Fed anticipates as strong nominal wage growth and fading effects of the pandemic pull more workers back into the labor force.

This is why the longer term outlook for extinguishing inflation is bullish.

I mentioned the risk of stagflation in the November 2021 newsletter. The likelihood of this scenario is not high, but it is rising.

Risks this quarter

Americans appear well aware of these risks which is the compounding issue underlying our joylessness:

(1) How the war unfolds in Europe, which is now a bigger issue than

(2) subsequent potential waves of coronavirus

(3) extended supply chain delays and disruptions which push

(4) inflation even higher,

(5) a stock market vulnerable to correction due to global weakness and/or escalating war

(6) higher interest rates and uncertainty for the housing market and investment

(7) no resolution for high oil prices and therefore gasoline prices anytime soon

An upside risk is that U.S. and global production could accelerate beyond expectations if war is resolved soon, and/or workers return to the labor force more rapidly to fill job openings, generate more income, increase spending, and therefore overall economic growth.

Stay tuned for updates . . . . .

1 Most Important Problem, Gallup Poll, March 2022. Inflation (together with oil prices) and the economy in general were by far, the principal concerns of Americans. See: https://news.gallup.com/poll/391220/inflation-dominates-americans-economic-concerns-march.aspx

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.

In response to the title of this newsletter: no; we are not back to normal. And I really don’t need to spell this out. Moody’s Analytics partnered with CNN to create the Back-to-Normal Index which uses 44 indicators to ascertain whether state economies have returned to pre-pandemic levels. The Back-to-Normal Index for California as of January 26 is 87 percent. Only Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Massachusetts and Vermont are lower among all 50 states. Many state economies have slipped recently, including California which has the highest unemployment rate in the nation.

In response to the title of this newsletter: no; we are not back to normal. And I really don’t need to spell this out. Moody’s Analytics partnered with CNN to create the Back-to-Normal Index which uses 44 indicators to ascertain whether state economies have returned to pre-pandemic levels. The Back-to-Normal Index for California as of January 26 is 87 percent. Only Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Massachusetts and Vermont are lower among all 50 states. Many state economies have slipped recently, including California which has the highest unemployment rate in the nation. Logistic Issues Persist

Logistic Issues Persist Into January 2022 we go and the pandemic continues; its future progression (or how long governments will continue to maintain a state of emergency in the name of public health) is uncertain. We generally believe the pandemic will be brought under control and that the disruptions and frictions it has caused in the labor market and to the supply chain will be resolved over time.

Into January 2022 we go and the pandemic continues; its future progression (or how long governments will continue to maintain a state of emergency in the name of public health) is uncertain. We generally believe the pandemic will be brought under control and that the disruptions and frictions it has caused in the labor market and to the supply chain will be resolved over time. Accepting substitutes for products we can’t get

Accepting substitutes for products we can’t get

These are the four biggest issues that we, as consumers and businesses are facing in 2021. Moreover, these issues will not be resolved by year’s end. An escalation of at least two of these issues is likely, given that we’ve seen very little resolution to date.

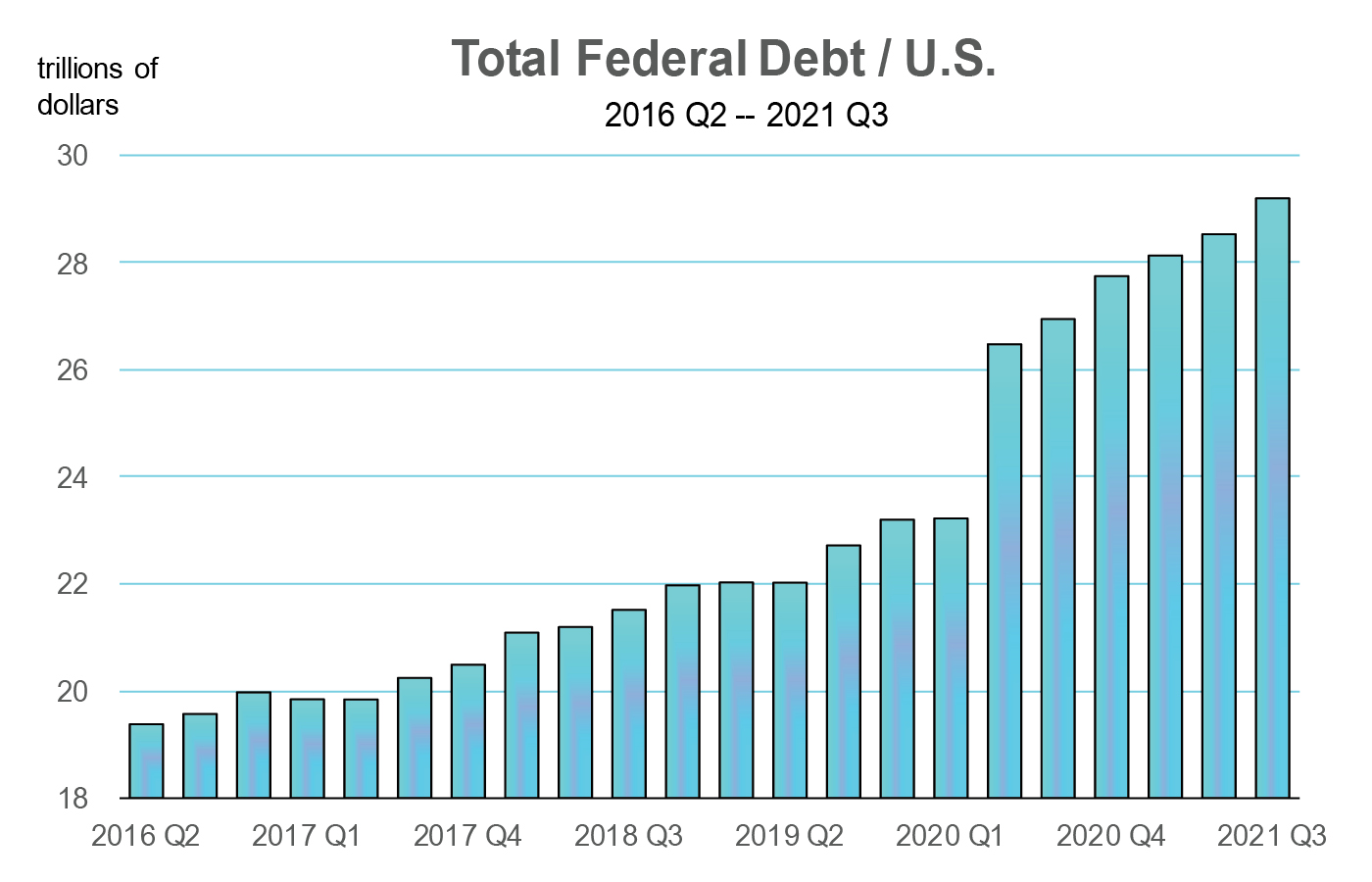

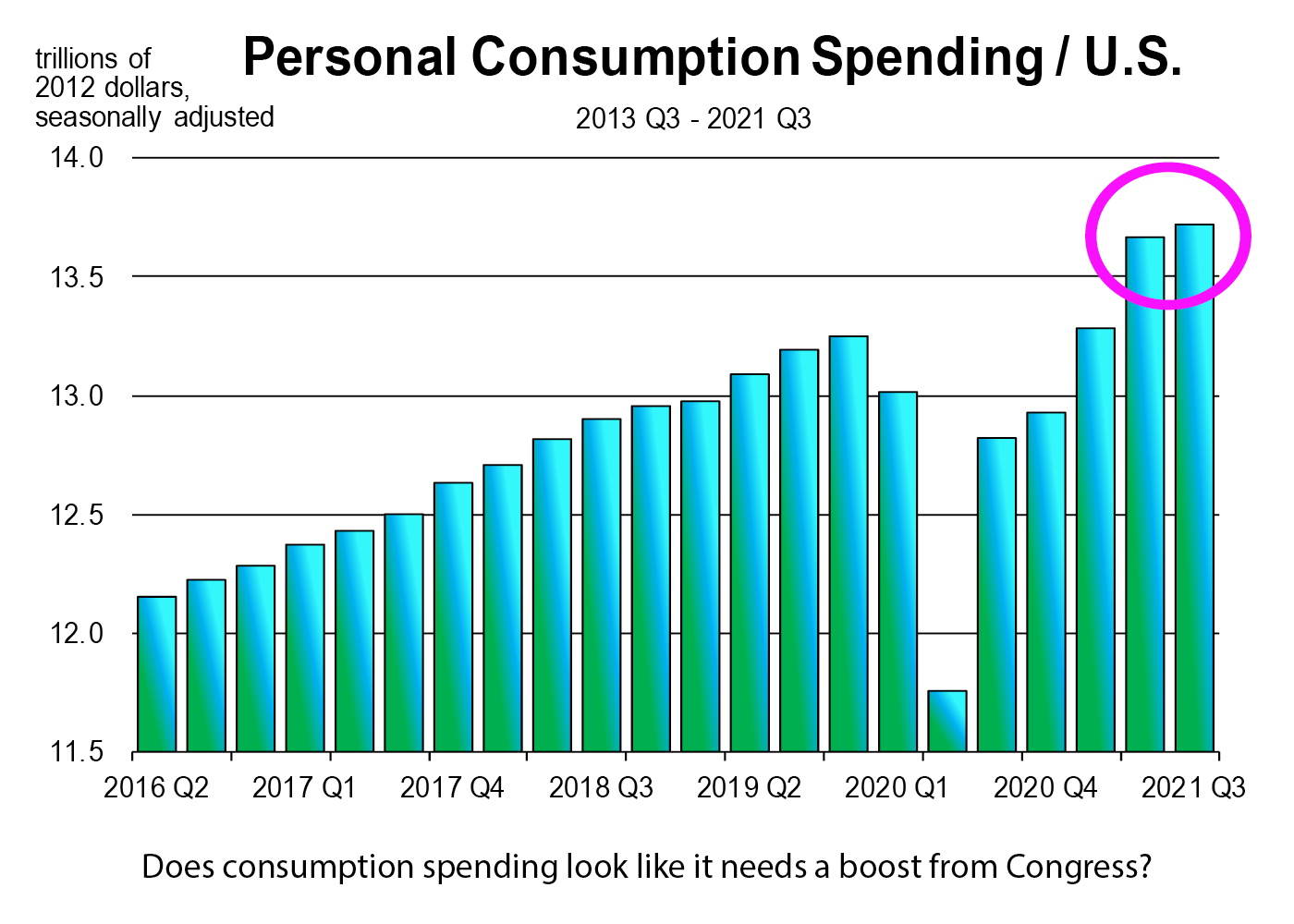

These are the four biggest issues that we, as consumers and businesses are facing in 2021. Moreover, these issues will not be resolved by year’s end. An escalation of at least two of these issues is likely, given that we’ve seen very little resolution to date. The current Congress has already passed $3.1 trillion in spending bills this year, creating not only a surge of federal debt, but a potential surge in government spending which is front loaded for 2022, 2023, and 2024.

The current Congress has already passed $3.1 trillion in spending bills this year, creating not only a surge of federal debt, but a potential surge in government spending which is front loaded for 2022, 2023, and 2024.

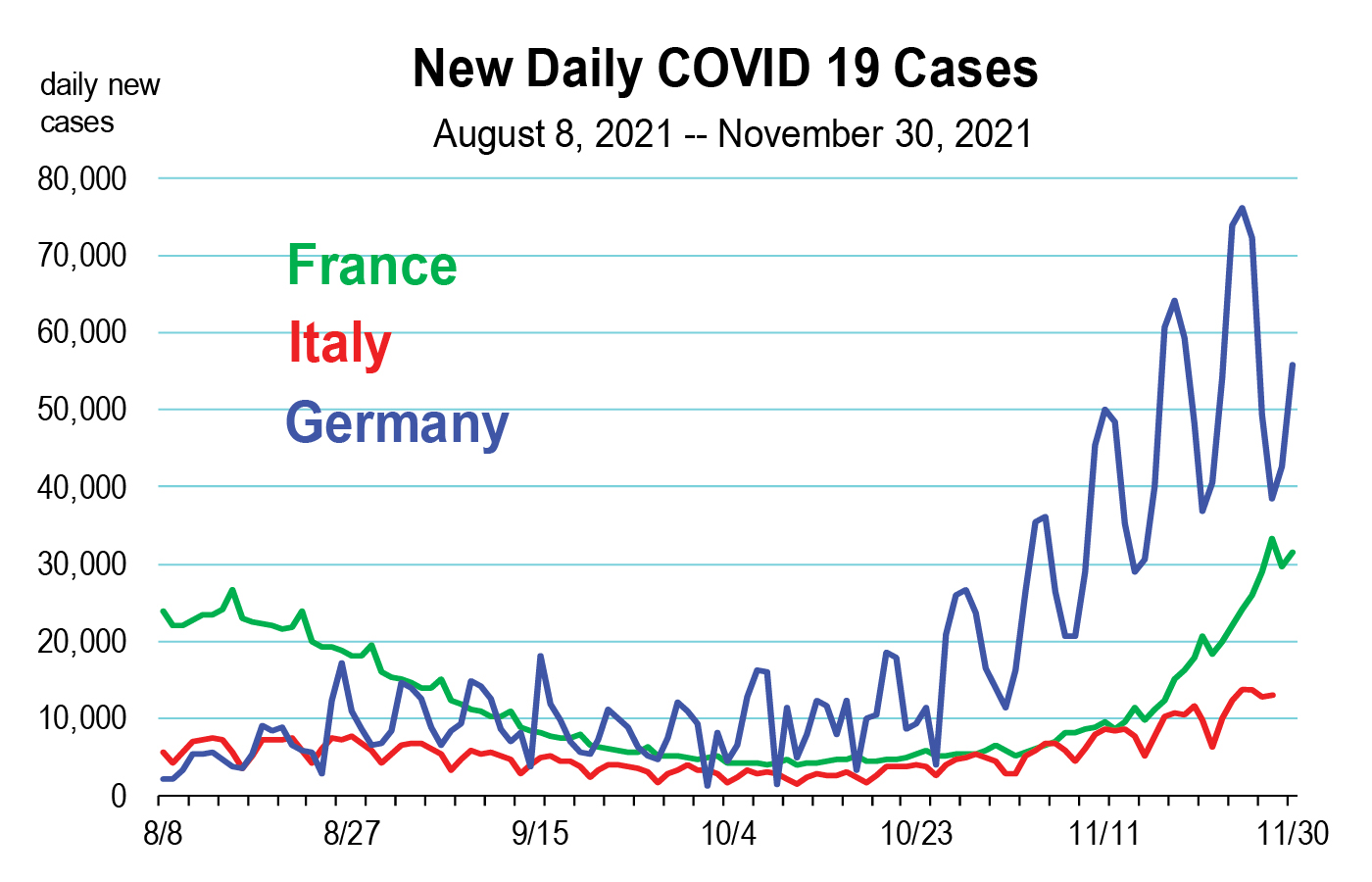

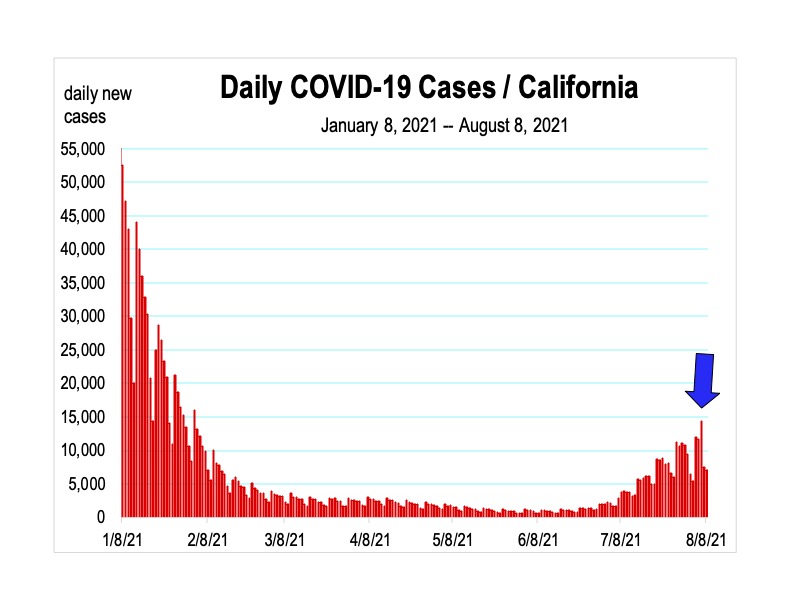

The global economic recovery remains tethered to the pandemic. And another wave is coming. We are seeing it in Europe, notably Germany and Austria. In Austria, a vaccine mandate and a national lockdown have now been imposed. In Germany, daily cases are now more than twice as high as they have ever been during the course of the entire pandemic.

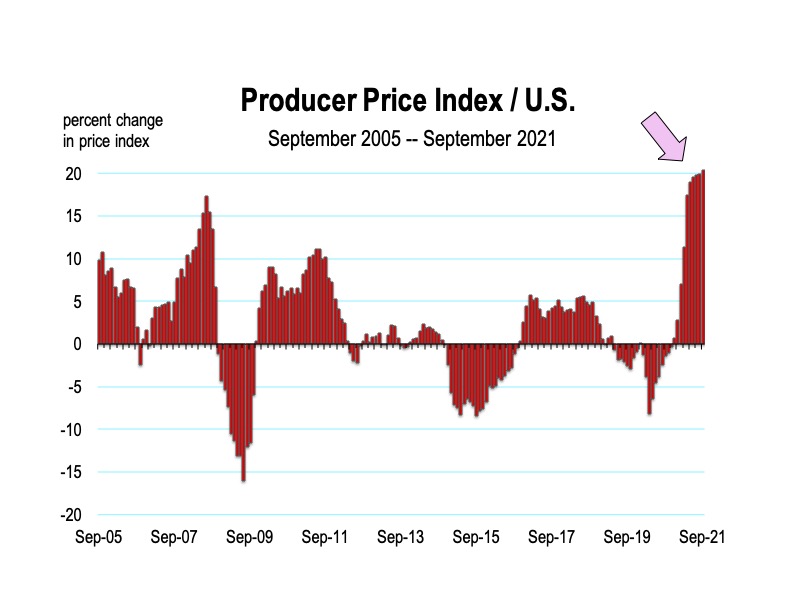

The global economic recovery remains tethered to the pandemic. And another wave is coming. We are seeing it in Europe, notably Germany and Austria. In Austria, a vaccine mandate and a national lockdown have now been imposed. In Germany, daily cases are now more than twice as high as they have ever been during the course of the entire pandemic. Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974.

Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974. The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

But what’s the chance?

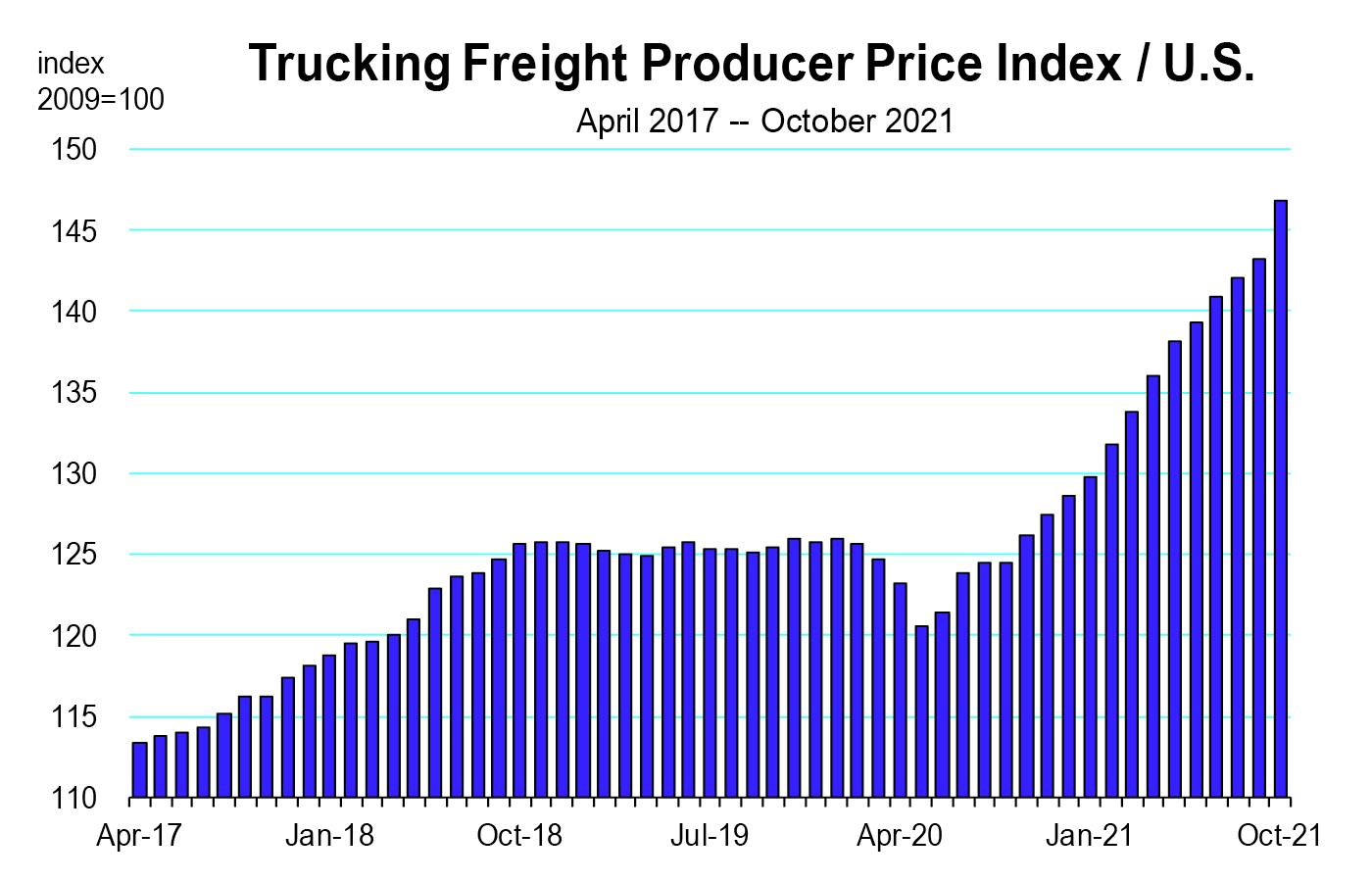

But what’s the chance? Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

by Mark Schniepp

by Mark Schniepp The impact on the economy of California was more significant than the rest of the nation but the recovery will progress at a faster pace, catching up to the U.S. by 2023.

The impact on the economy of California was more significant than the rest of the nation but the recovery will progress at a faster pace, catching up to the U.S. by 2023. The Great Resignation

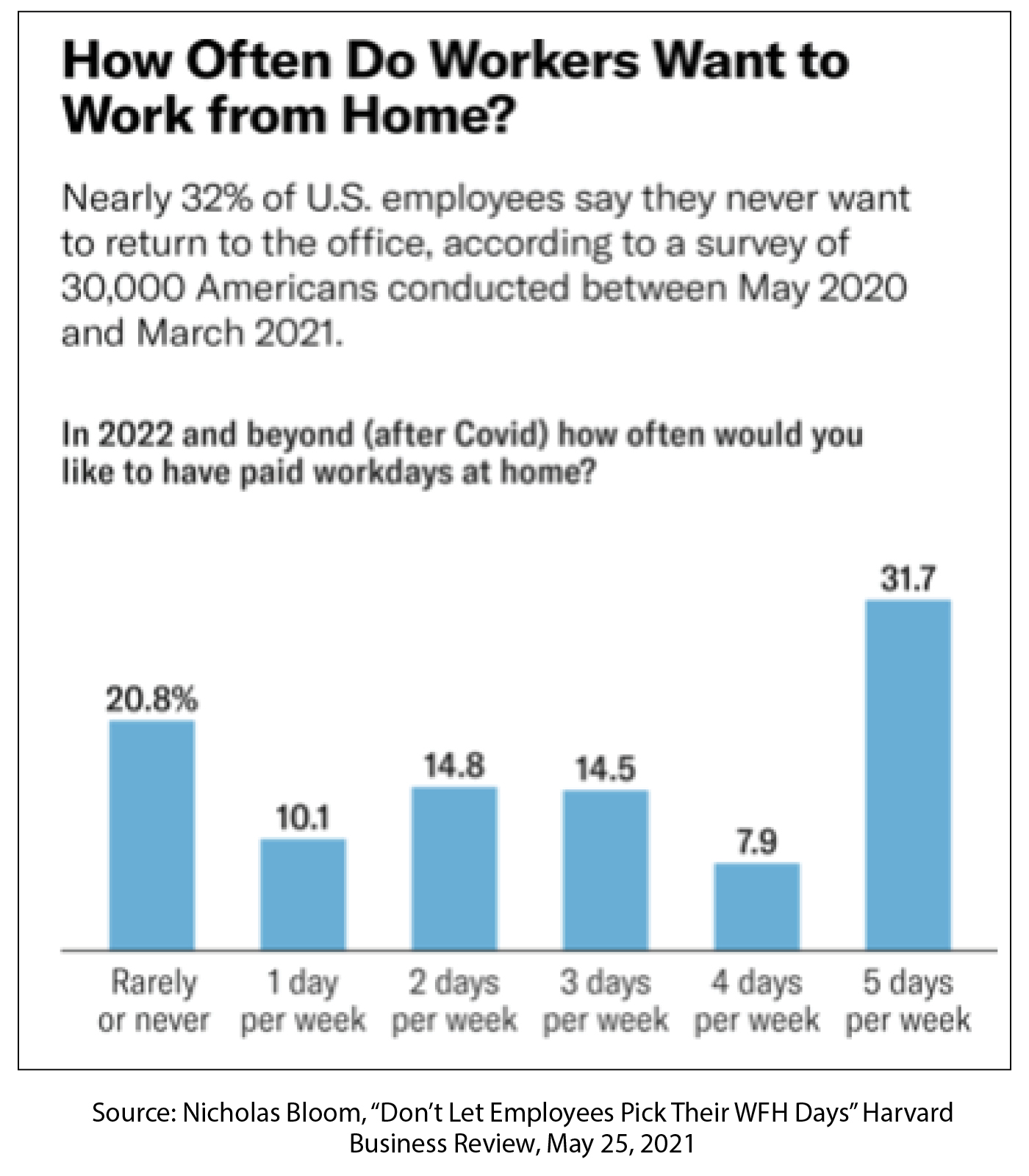

The Great Resignation Remote work and virtual meetings will continue

Remote work and virtual meetings will continue by Mark Schniepp

by Mark Schniepp

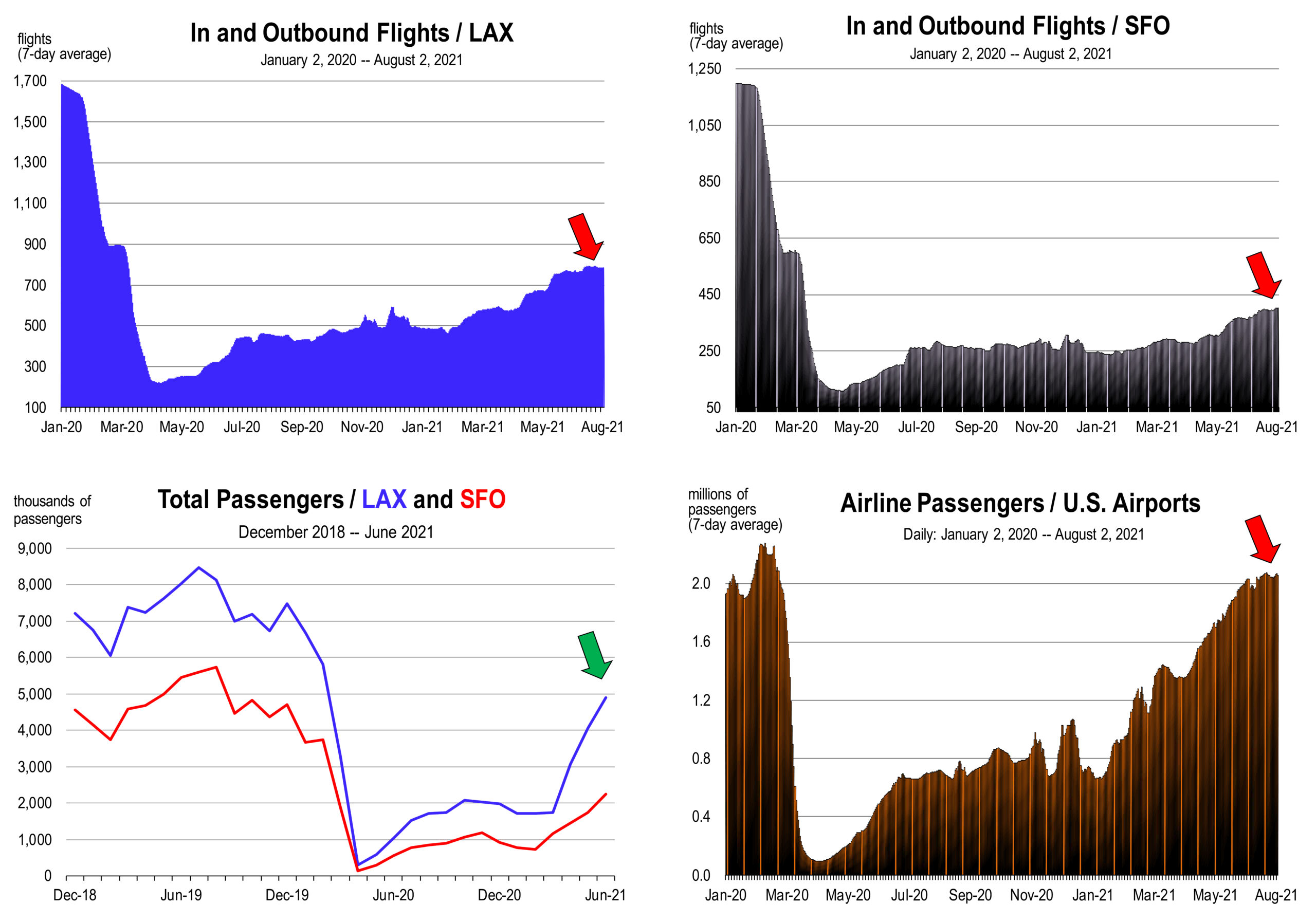

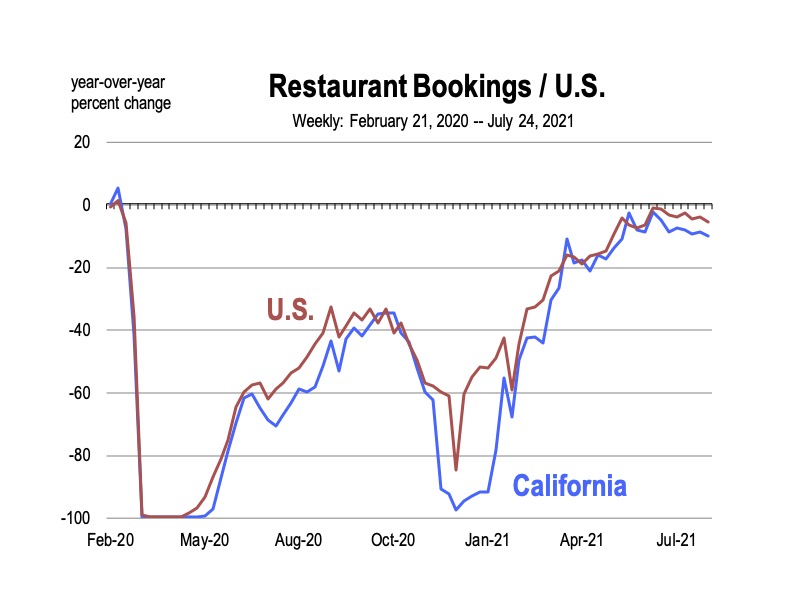

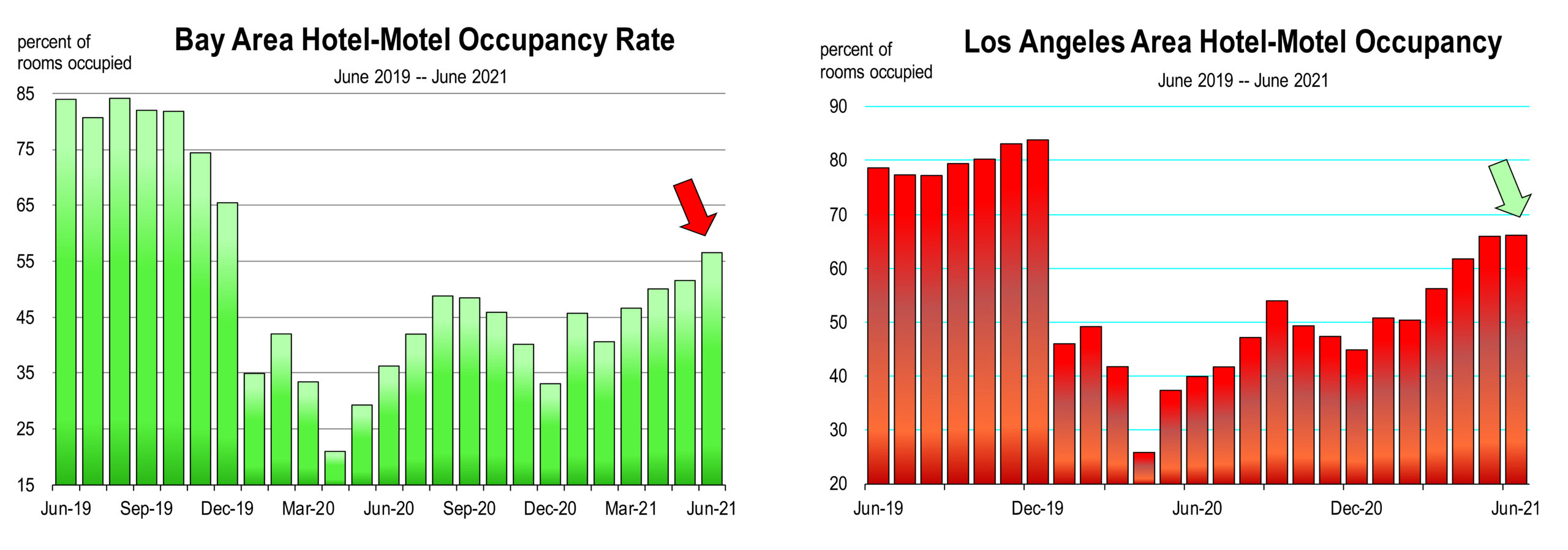

While air passenger travel in California has recovered 66 percent, passenger travel nationwide has recovered nearly 80 percent, and the clear increase in travel has produced higher hotel-motel occupancy rates.

While air passenger travel in California has recovered 66 percent, passenger travel nationwide has recovered nearly 80 percent, and the clear increase in travel has produced higher hotel-motel occupancy rates.

Travel related price increases are very likely catchup from the steeply discounted prices offered a year ago when no one was traveling anywhere.

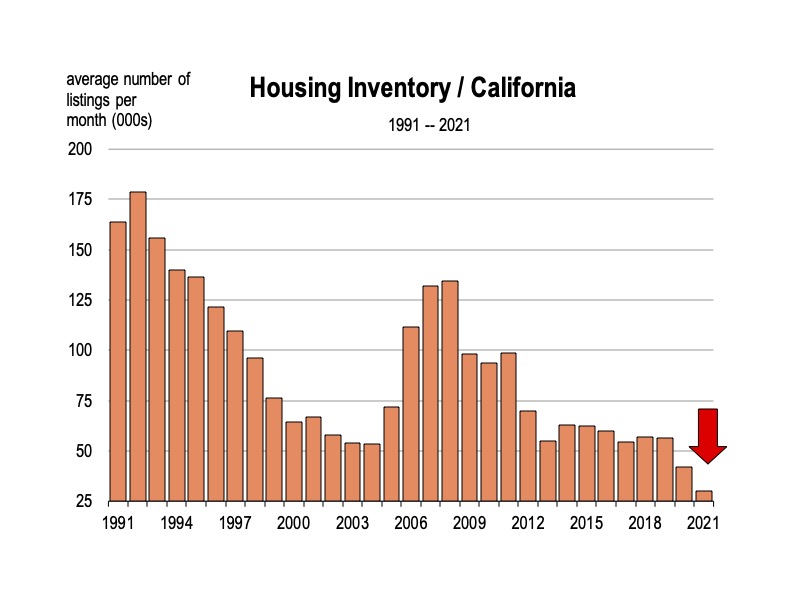

Travel related price increases are very likely catchup from the steeply discounted prices offered a year ago when no one was traveling anywhere. Only 1.16 million homes were on the market in April, a 20 percent drop from a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors. In California, over the last 6 months, inventory levels have declined to their lowest on record.

Only 1.16 million homes were on the market in April, a 20 percent drop from a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors. In California, over the last 6 months, inventory levels have declined to their lowest on record.