by Mark Schniepp

October 7, 2021

Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

Global supply disruptions continue to hamper the U.S. economy, contributing to the acceleration of inflation. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to notice the clear evidence that supply-chain issues are creating economic costs.

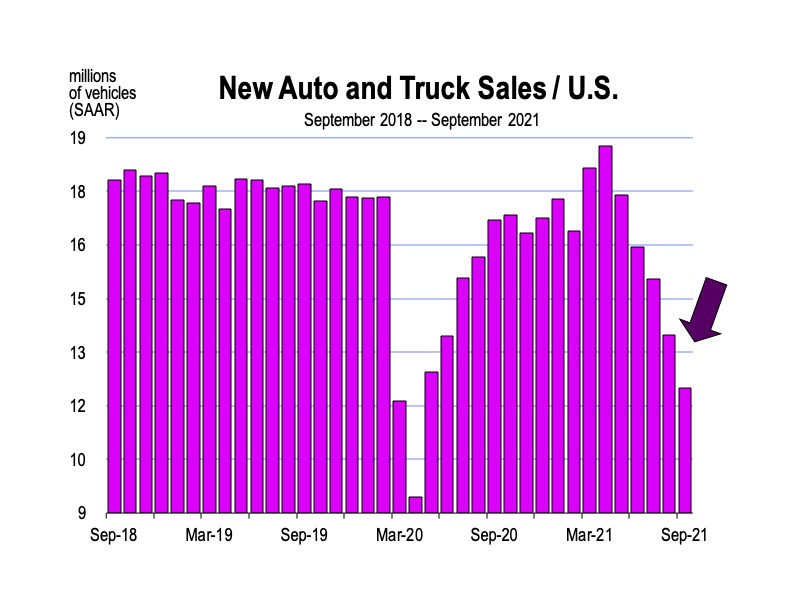

Looking at this chart of new U.S. vehicles sales each month through September, you’d think that consumer demand for autos was falling like a rock. Normally that’s what tends to drive the variation in this series. This time however, it’s a supply issue, indicative of many product supply constraints today.

Usually, cars are like Doritos—they can always make more—but cars utilize semi-conductors to run most of their internal and external systems. And now there is a semiconductor supply issue from Asian producers, due to intermittent factory shutdowns because of COVID-19, limiting production.

A spate of supply “shortages” emerged when ocean carrier sailings were cancelled, manufacturing capacity was cut, and workers everywhere were displaced. Circumstances where the growth of demand for a product is outpacing the growth of supply—and this includes the scenario where the normal volume of supply has been interrupted—manifest as shortages. The latter circumstance has pushed prices higher, adding to the surge in inflation this year.

Many products that we import—including coffee and Nike shoes—are further delayed into seaports because of problems with ships and containers. The world-wide pandemic-induced demand for PPE rerouted containers and ships about the globe, or shut down ships entirely during much of 2020. These particular outcomes have interrupted shipping schedules and the normal supply of shipping containers. Factory shutdowns or dockworker quarantines due to coronavirus outbreaks further exacerbated the supply issues.

The Great Shipping Debacle

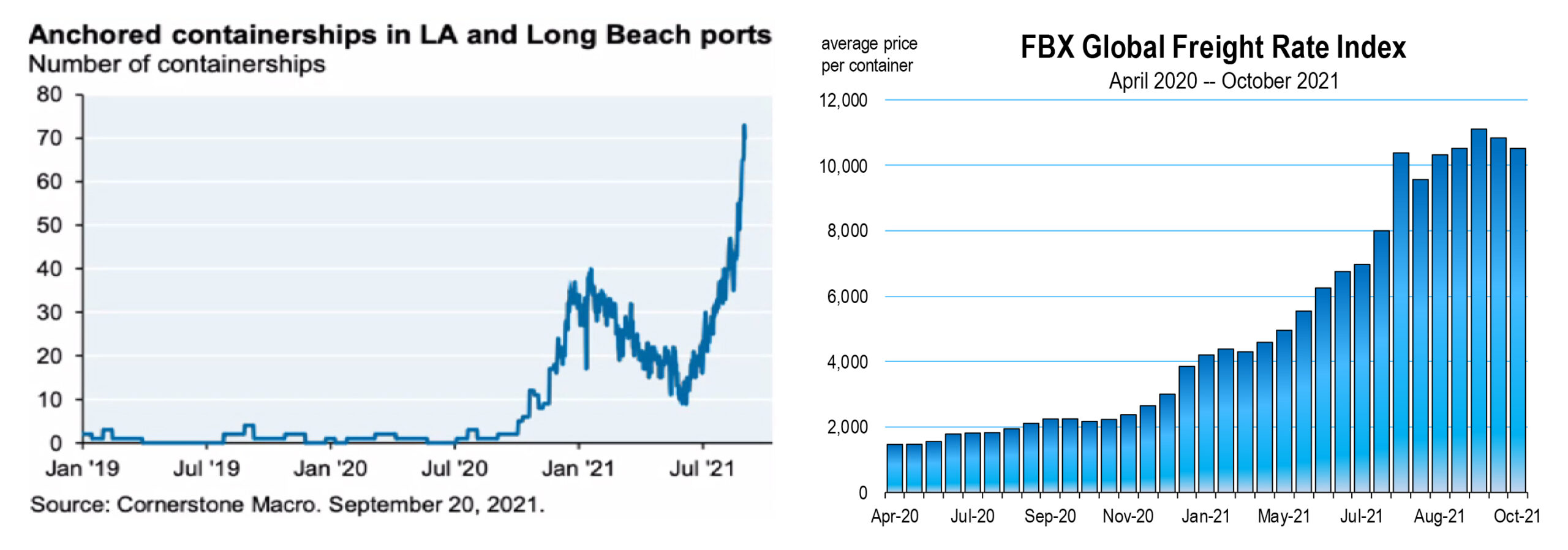

Dozens of mega-container ships are waiting off the coast of Los Angeles to dock at the Ports of LA and Long Beach. The route into San Pedro Bay accounts for about one-third of all US imports, and the backlog is causing ships to wait weeks to dock and unload. The mega-ships take much longer to unload, and they carry millions of dollars worth of furniture, auto parts, clothes, electronics, and plastics. Backlogs in most of these goods are seriously piling up.

As of late September, more than 70 container ships are anchored in the San Pedro Bay, a record number. The lack of having all of the goods unloaded at the Ports and transported to markets results in (1) shortages of products, and (2) rising prices for these goods to alleviate the shortages.

Thousands of containers are still stuck in unfamiliar routes or are stuck on ships waiting to unload. Fewer containers are in normal circulation which is causing the existing container supply to rise steeply in price as companies compete for them.1

Container prices have quadrupled or quintupled in one year. Rising container prices increase the cost of shipping, which increases the end-product costs to consumers. Container prices will ultimately normalize but it will take time.

The largest question bankers, economists, and company CEOs can’t answer with certainty is this: Are the shortages and delays merely temporary mishaps accompanying the resumption of business, or something more insidious that could last well into next year?

Consumers who continued to consume through the pandemic exhausted inventories of goods that the idled factories and delayed ships were unable to replenish. This rate of consumption continues today. We originally assumed that factories would catch up and ships would work through the backlog in a few months.

Not so. Coronavirus-related closures of key ports in Asia, the intermittent factory shutdowns, and the delayed unloading of waiting container ships has extended the catch-up period.

Now with Christmas approaching, consumer demand for goods will accelerate, creating further competition for limited supplies carried by the crippled supply chain, which will further add pressure on prices. This is demand-pull inflation. And it is likely to persist at least into next year.

Trucking

The primary source of container transport when the cargo is unloaded is trucking. A “shortage” of drivers translates into container volume that does not get moved to its destination on time. The driver workforce has been reduced by safety concerns, care giving priorities at home, expanded unemployment benefits, and other job openings offering a better lifestyle.

Wages are rising sharply, but the process to lure (and/or train) enough workers back into the industry will be lengthy. The truck driver shortage may be the most acute of bottlenecks in the supply chain, and it does not bode well for a rapid resolution of the overall disruption.

Delta

The bite of the Delta variant on the economy is easing. New infections and hospitalizations have dropped as the worst of the current coronavirus wave is clearly receding.

But it’s likely that Delta extends the supply-chain issues, particularly for semiconductors. Though there are a significant number of shortages now, domestic production for a number of them are improving, and this should ease some price pressures soon. The Delta variant still creates some upside risk to inflation. If the highly transmissible strain prompts fewer workers to return to the labor force, it may require businesses to further bid up wages and pass on the extra labor cost to consumers. This is cost push inflation, which is difficult to address with either fiscal or monetary policy.

Consequently, we need infections to abate, the economy to remain open, and the labor force to expand to avert the vagaries of cost push inflation, which is the more pernicious form of inflation, and can lead to stagflation.

GDP estimates for the third quarter have been scaled downward, but not sharply. The annualized rates are now between 3.3 and 3.9 percent, and rising to 4.3 percent in the fourth quarter, the period we are currently in now.

1 When the Suez Canal was blocked in March by the Ever Grand, it stranded thousands of containers and caused backlogs and delays in shipping schedules that lasted months. Vessels had to wait for the canal to open or take a much longer route around Africa. The shutdown of a key port in southern China in May and June left approximately 350,000 containers idle.

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.