by Mark Schniepp

November 5, 2021

The GDP outcome for the July to September period this year was very disappointing. And with year-to-date inflation running at 5.3 percent—the highest rate of inflation in 13 years—there are mounting concerns that the U.S. economy may be heading into a stagflationary period of the business cycle.

What is stagflation?

Stagflation is when there is both inflation and stagnant (or sluggish) growth of economic output. A period of stagflation has not occurred in the United States since the 1970s, so there is little precedent for predicting that such an outcome will belie the current economy.1

The supply chain issues (that I wrote about at length last month) and the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus in 2020 and 2021 have contributed to current consumer price inflation, which is more than twice the rate that we experienced over the 2012 to 2020 period.

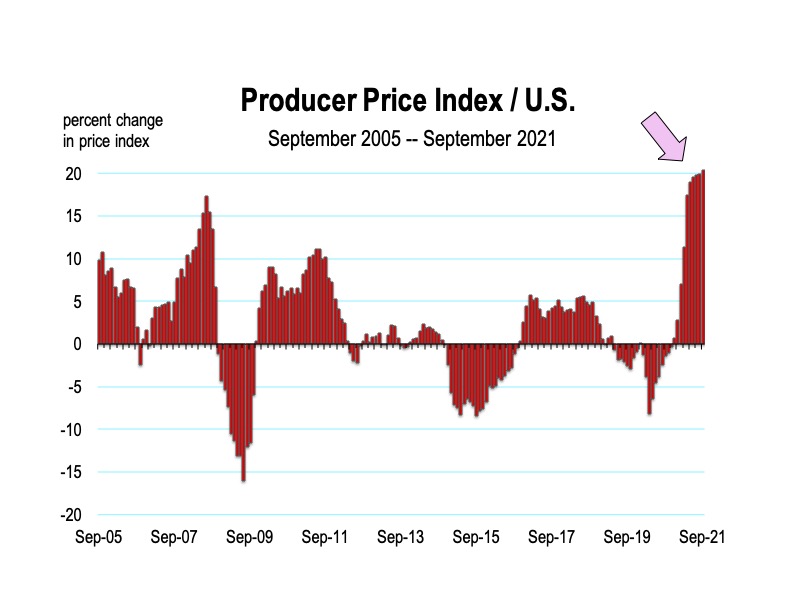

Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974.

Moreover, producer price inflation has now hit 20 percent year-over-year. This is the highest rate of inflation in producer (or wholesale) prices since 1974.

The economy appeared to be in horrific condition in the Spring of 2020, prompting the administration and Congress to pass a $3 trillion spending program to restore income to businesses, organizations, and workers lost from a shutdown economy. This was just the beginning of a massive fiscal policy response to the pandemic.

Opening up in May and June of 2020, the economy bounced back sharply. Conditions were not as dire as presumed and incomes remained surprisingly resilient, helped by the CARES Act. Consumers then went on a buying binge (which has yet to materially cool) and this is the fundamental impetus for the current supply chain debacle.

Then another $900 billion stimulus program was initiated in December 2020. This included more helicopter money and PPP loan funding to keep businesses viable. Then another $1.9 trillion of spending (including more helicopter money) was approved in March 2021. The U.S. response to the pandemic is an order of magnitude larger than the response to the 2008 global financial crisis.

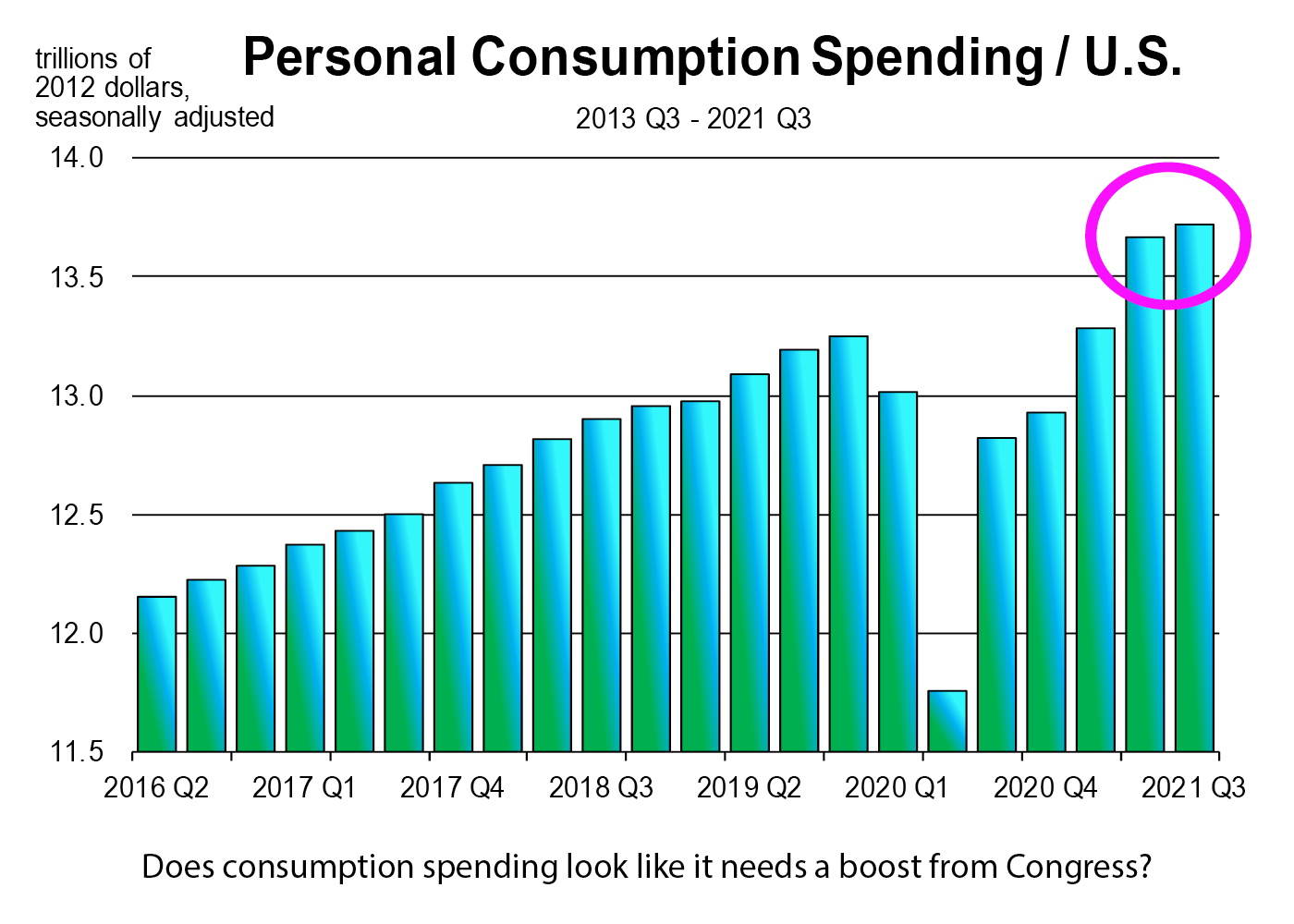

If the current $3 trillion in proposed spending by Congress is approved including the infrastructure bill and the Build Back Better bill, we will see much of this injected into the economy at a time in which the recovery would be better left alone. More massive government spending will likely exacerbate inflation by further stimulating already steady demand for goods and services.

Supply shocks precipitated the stagflation of the 1970s. Currently, the post-pandemic supply bottlenecks represent a current shock because it has largely been unanticipated. So-called “shortages” are occurring where we can’t sell enough automobiles, pet food, or beef to consumers who want this stuff, reducing some production and output value. Meanwhile, the demand for labor remains extraordinary, the unemployment rate continues to decline, and general consumer demand for products does not appear to be moderating. Remember, federal stimulus money throughout 2020 and into 2021 including enhanced unemployment payments along with work from home that kept office workers and teachers employed, maintained incomes throughout the pandemic.

The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

The persistence and/or increase in inflation would have meaningful economic and financial consequences. And I believe we are more apt to see a persistence of inflation than we are to see stagnant growth because the evidence for the latter is relatively absent today.

Growth Prospects Going Forward

The Delta variant and FDA approval of the Pfizer vaccine are encouraging more people to get vaccinated, bringing the country closer to herd immunity with 58% of Americans fully vaccinated as of November 3. Moreover, the U.S. economy has felt less impact with each wave of the virus and has generally been able to withstand the damage.

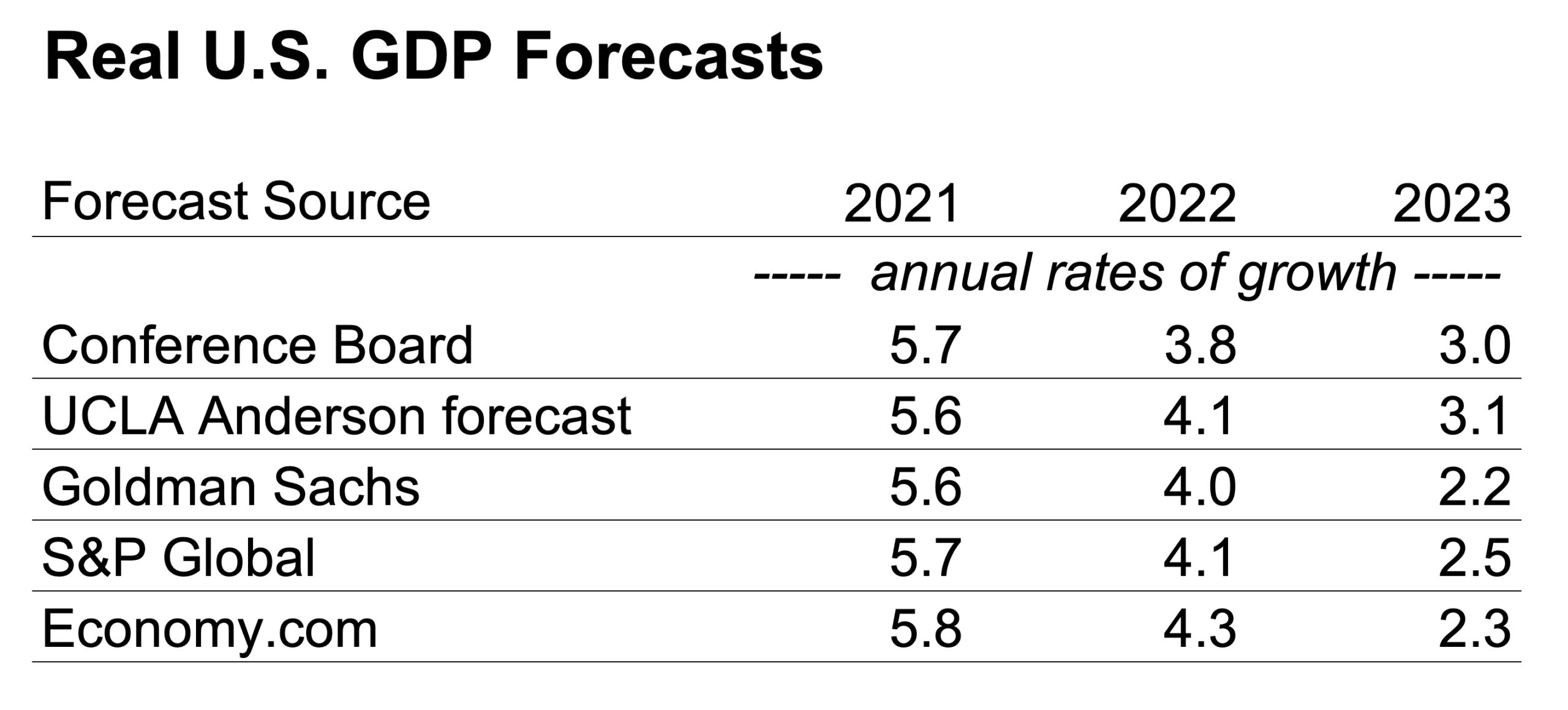

For context, the U.S. economy grew 6.7 percent in the second quarter this year, and then 2.0 percent in the third quarter. The near-term health of the U.S. economy remains strong and current GDP forecasts (as of October 2021) range from a low of 4.3 percent to a high of 6.3 percent.

Furthermore, the International Monetary Fund projects 5.9 percent growth for the global economy in 2021 and 4.9 percent in 2022. These rates of growth are hardly stagnant if they are realized.

Risks and Scenarios for Stagnant Growth

How does the economy fall into stagnation? Any combination of these scenarios would negatively impact growth. The disruption to the global supply chain along with new variants are perhaps the most probable in terms of potential threats to the economy in 2022.

Consider any of the following:

- The current vaccines are not effective against new variants and a new wave of cases precipitates renewed interventions, such as social distancing, school closures, and the cancelation of large events again. Stricter interventions are probably not likely.

- People cut back on services they perceive as “risky” amid new virus outbreaks.

- Financially stretched businesses fail with no new rounds of fiscal rescue.

- Current supply constraints escalate, limiting production and growth. Supply shortages also limit consumption spending.

- Overloaded supply chains drive up operating costs and prices leading to higher rates of inflation.

- Higher rates of inflation, and the exhaustion of stimulus money received by households and their savings also reduces consumption.

- The Fed raises rates sooner than expected and more than expected, causing demand for interest sensitive goods to decline. Economic growth slows below potential in 2022 and 2023.

But what’s the chance?

But what’s the chance?

I put the chance of these downside risks at less than 50 percent, but higher than 10 percent. Growth this quarter and going into 2022 should remain high because households want to spend their bloated savings from the past year. They are also demanding more entertainment and are dying to travel having foregone both since March of 2020.

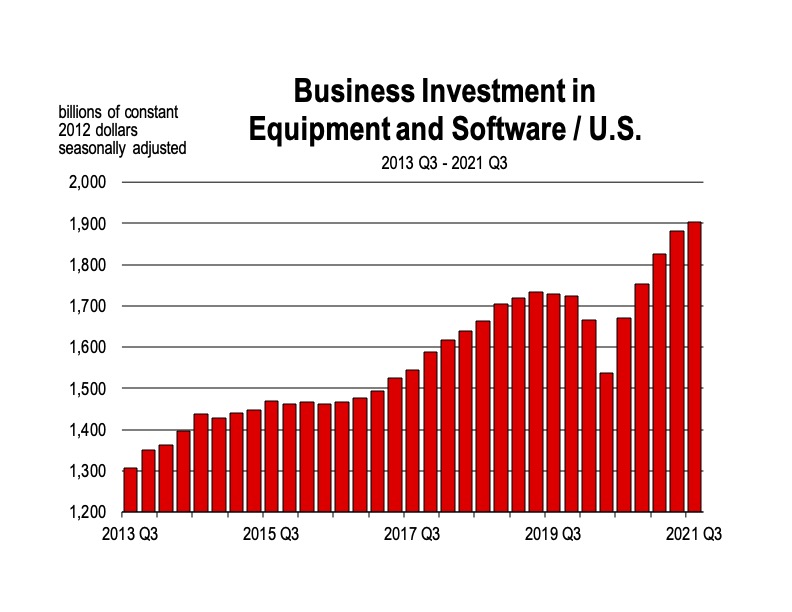

Business investment also continues to increase, especially in IT equipment and software. And housing demand precipitates much higher residential investment in 2022 and 2023. We don’t need Congress to pass any more spending bills for economic growth to remain solid over the next year or two.

I don’t think there will be the “stag” in stagflation, but I’m less certain about the transitory nature of the “flation” part. Inflation could accelerate and hang around into 2023. That means the damage of higher prices is being baked into the cake we plan to consume over the next two years.

1 The stagflation of the 1970s came after the crude oil supply shocks following the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Inflation soared to 11 percent in 1974 and 13.5 percent in 1980. Meanwhile GDP growth averaged 2.5 percent per year from 1974 to 1980 and was negative in three of those years. The unemployment rate over this period averaged 7.0 percent. The S&P 500 Index declined from 579 in January 1974 to 386 in December 1979.

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.