by Mark Schniepp

September 2017

The current environment for housing in California is being routinely referred to as a crisis. Many consider it a bubble and anticipate the possibility of another crash.

For California, the “housing crisis” is a direct consequence of the state’s economic boom. And 30 years of resistance to housing development has resulted in an onerous environment for the creation of new housing today. California has always been a desirable place to live and over the decades has gone through periodic spasms of high housing costs. However, a booming economy and the lack of construction of homes and apartments have conspired to produce the current housing crisis.

The Heart of the Problem

The economic recovery and expansion have not occurred without consequences.

The technology revolution, epicentered in California and in particular the Bay Area,

has resulted in the creation of thousands of higher paying jobs. The record levels of foreign and domestic visitors vacationing in California has also pushed job creation in the visitor serving industries to all time record levels. The aging of the baby boomers and the Affordable Care Act are responsible for pushing employment in healthcare jobs to all time record levels.

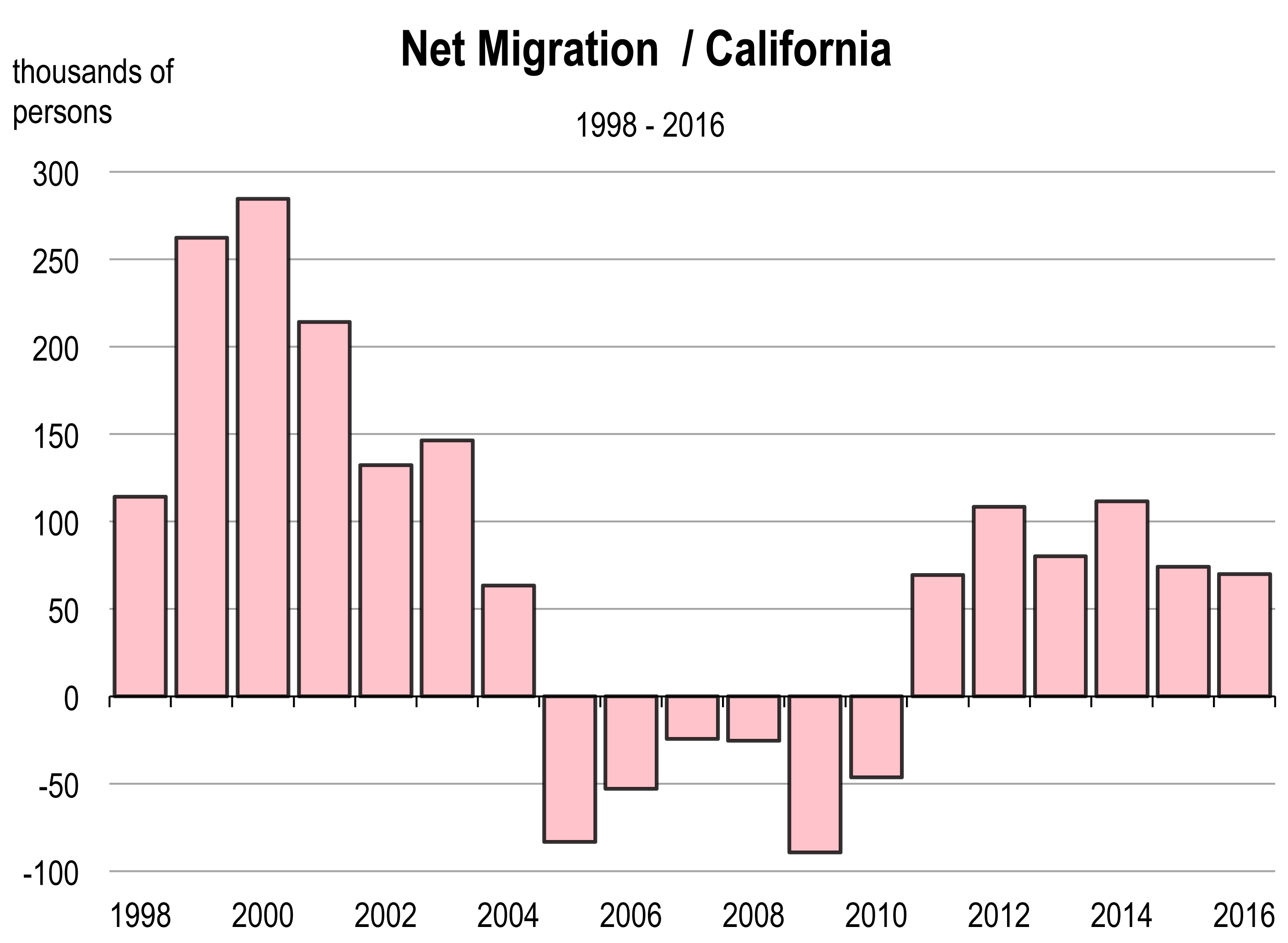

The tech boom, the visitor boom, the healthcare boom, and the professional services boom have employed every California resident that wants a job and encouraged an estimated 512,000 net migrants into the state from 2011 to 2016.

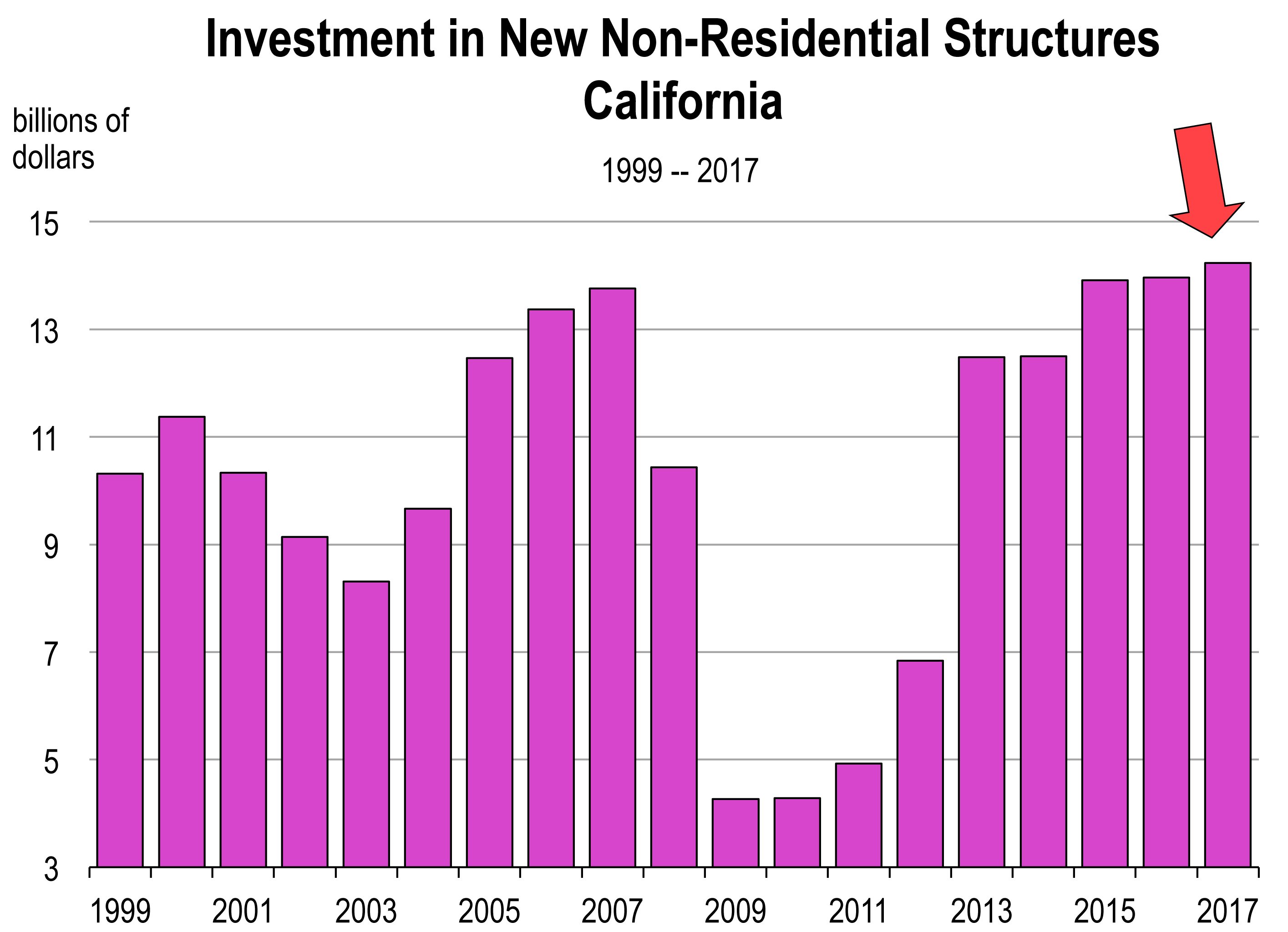

The strong demand for and consequent creation of millions of new jobs since 2010 has encouraged extensive office development in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Orange County, and Santa Clara Counties.

But these counties have failed to build a commensurate amount of housing, for new workers and new in-migrating populations.

Cities have built high tech research parks and innovation campuses but have failed to build housing. Consequently, a major imbalance has resulted and this imbalance has manifested in sharply rising home prices and apartment rents since 2011.

The high cost of housing is principally a failure to build.

Proposition 13

And then there is Proposition 13 which caps property taxes, discouraging owners to sell their properties and face a major tax reset. And in recent years with property values escalating to all time record highs in the state, the disincentive to sell is too great so there is far less for-sale inventory of existing homes that would typically provide for a lot more inventory.

Furthermore, cities receive very little in property taxes from homes whose value has not reset in the last 10 or 20 years. Consequently, this fiscal disincentive which grows larger over time gives communities little reason to permit more housing, especially when the neighbors already oppose it for all the usual reasons.

Supply Limitations

Cities and Counties use zoning, environmental laws and procedural laws to oppose, discourage, and/or deny residential projects deemed too large or out of character.

There are also growth restrictions put in place by voter referendums that directly or indirectly limit housing development. Examples of these are density and height restrictions, or an actual limit on housing unit development.

Cities that deny housing are a principal and direct cause of the housing crisis.

The lack of housing supply, together with the demand for housing encouraged by a strong economy and record creation of jobs and income, has created a political environment where prospects for a state housing intervention appear more likely than ever.

Housing Elements

Since 1969, California has required that all local governments (cities and counties) adequately plan to meet the housing needs of everyone in the community. California’s local governments meet this requirement by adopting housing plans as part of their “general plan.” The law mandating that housing be included as an element of each jurisdiction’s general plan is known as “housing-element law.”

California’s housing-element law acknowledges that, in order for the private market to adequately address the housing needs and demand of Californians, local governments must adopt plans and regulatory systems that provide opportunities for (and do not unduly constrain), housing development. Consequently, housing policy in California rests largely on the effective implementation of local general plans and, in particular, local housing elements.

However, providing opportunities under the housing element law and actually approving and permitting housing units are not the same. Getting the homes built is largely ignored by most jurisdictions in California today. Why? Because there is no real penalty for denying housing, even if there is adequate zoning for it.

The myriad of association of government agencies in California help to develop a RHNA for each county and city to follow for their zoning of housing. RHNA stands for Regional Housing Needs Allocation.

RHNA is supposed to enable cities and counties to anticipate their growth so that their quality of life is enhanced. And this includes producing a fair share of regional housing to accommodate anticipated growth.

However, too frequently, cities and counties use their planning processes as complex and complicated systems that confuse and frustrate prospective developers who must navigated through a labyrinth of requirements. It is often a highly discretionary process that effectively obstructs housing and therefore anticipated growth.

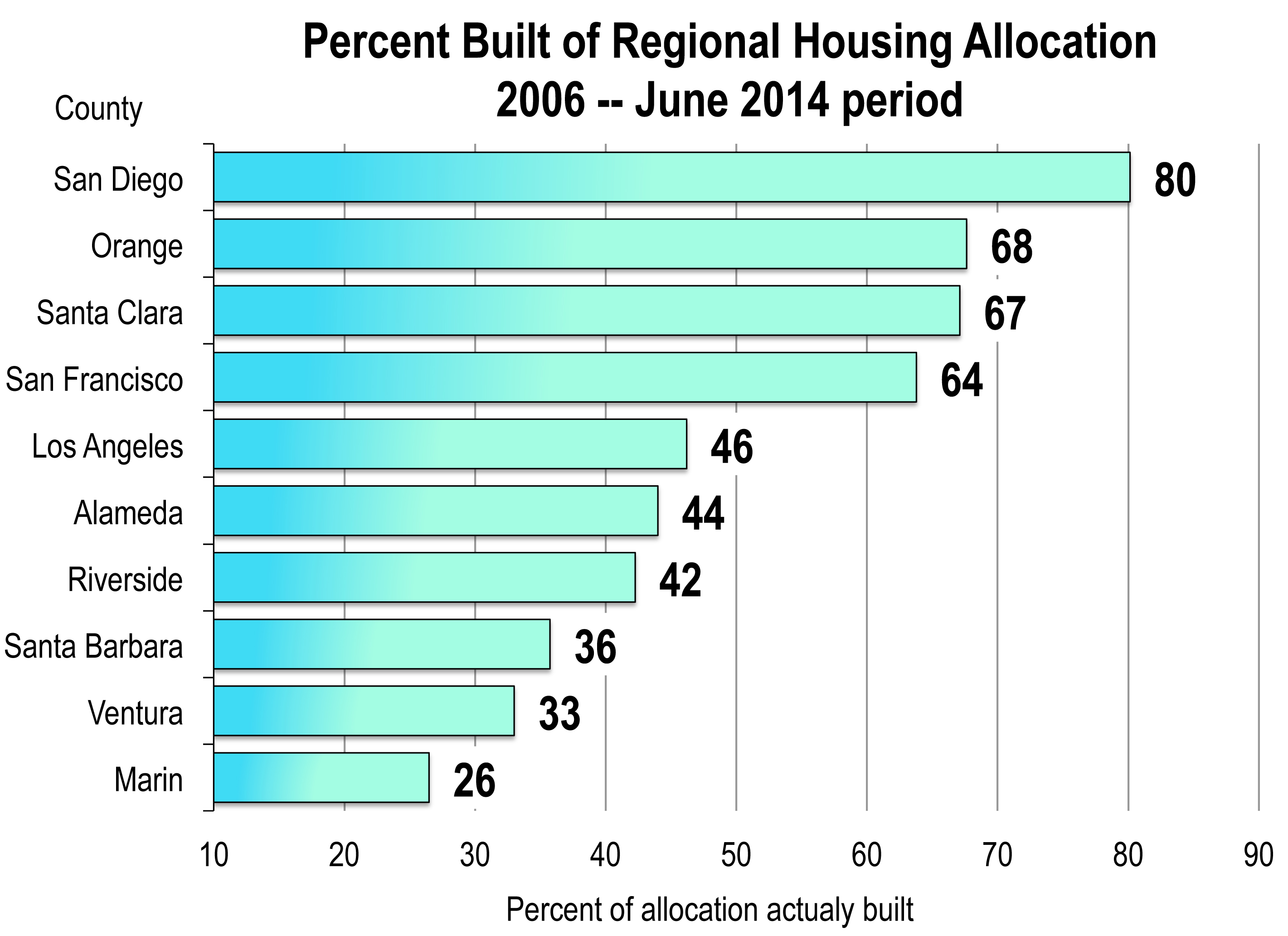

The most recently completed RHNA planning period is January 1, 2006 to June 30, 2014 for most Southern California counties. For this time period, housing estimates were developed based on population, employment and household growth projections. In Southern California, a total of 821,000 housing units were allocated. Only 404,500—less than half—were built. In the Bay Area, 215,000 housing units were planned for. Only 116,000 were built.

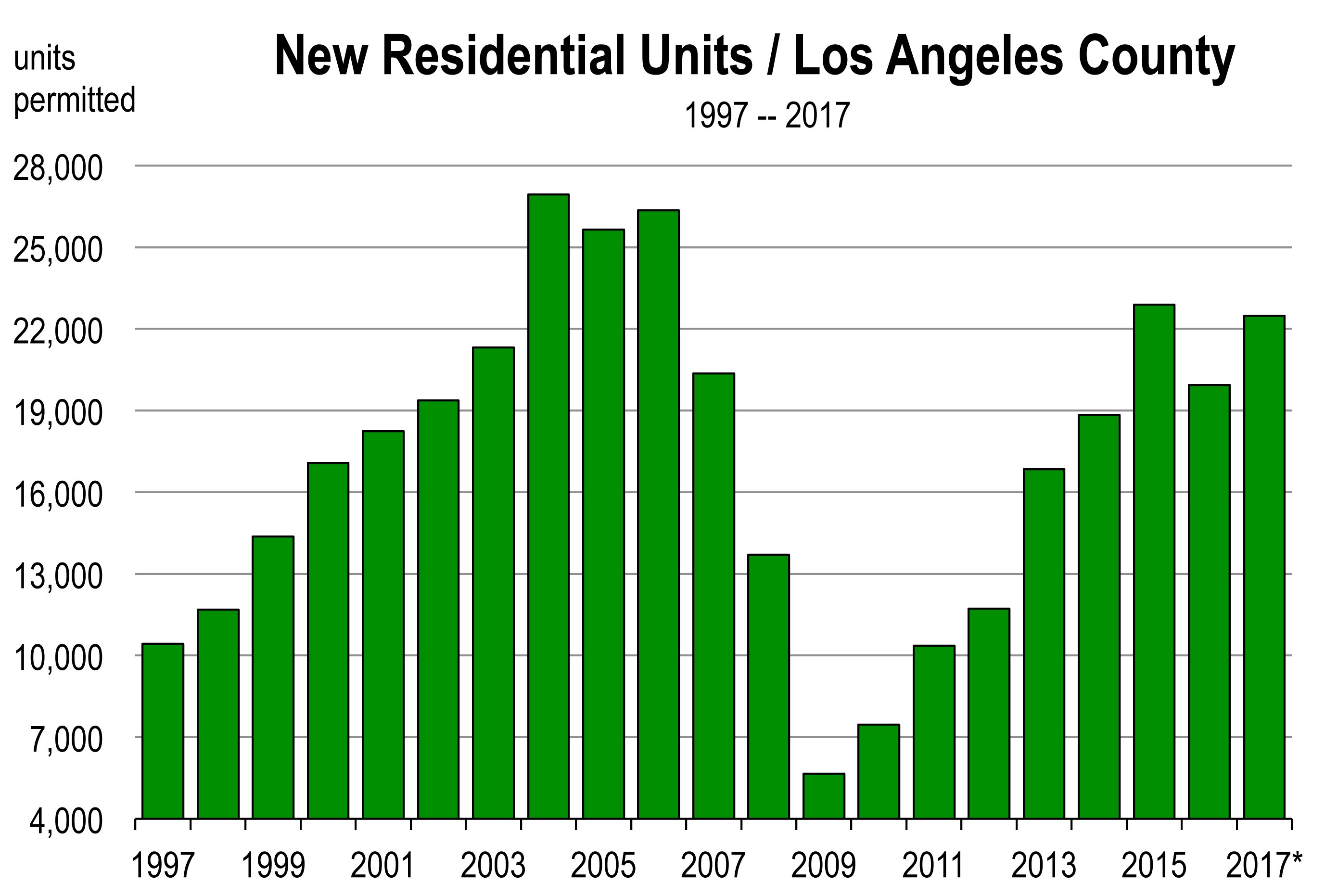

For the 2014 to 2021 planning period, the RHNA allocation for Southern California is 412,000 housing units, of which 180,000 are in Los Angeles County and 19,000 are in Ventura County. Permitted housing in L.A. County is currently on a pace that could meet the RHNA allocation. However, Ventura County is way behind.

For the 2014 to 2021 planning period, the RHNA allocation for Southern California is 412,000 housing units, of which 180,000 are in Los Angeles County and 19,000 are in Ventura County. Permitted housing in L.A. County is currently on a pace that could meet the RHNA allocation. However, Ventura County is way behind.

Bills in Sacramento to Help Resolve the Housing Crisis

The general notion prevailing today is that the state needs to do more to penalize cities and counties that are blocking development before agreeing to spend more dollars subsidizing projects.

There is currently one law on the books from 1982, the Housing accountability act, which requires cities to approve housing projects if they meet 3 fundamental criteria. Cities often interpret the criteria with discretion, and projects are downsized or denied. Predictably, there has been a spate of lawsuits over the years between developers and cities arguing whether the criteria have been met.

There are now three more bills in Sacramento looking to move forward this Fall:

SB35 Affordable Housing: streamlining the approval process

This bill essentially forces housing recalcitrant cities to eliminate impediments to new housing development and accept a streamlined entitlement process from HCD for approving new housing developments.

HCD is the California Department of Housing and Community Development that promotes policies and programs to expand affordable housing.

SB 3 The Affordable Housing Bond Act of 2018

This effort would place a $3 billion bond for low-income apartment housing on the November 2018 ballot.

AB 1505 Inclusionary Housing

This potential law would require that any new development of rental housing include a certain percentage of affordable rental units.

Rent Control Initiatives by Tenant Coalitions

Momentum is now building again for the implementation of rent control to cap rental rates on housing in California. Currently about 15 cities have some form of rent control, including San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles.

A bill has also been submitted in the California Assembly to repeal a 1995 state law—the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act—that limits the scope of local rent control laws. AB 1506 seeks to eliminate rent control exemptions for duplexes, condos, and single family homes to enable rents to be capped on newer housing stock built after 1995.

And in the November 2016 election, rent and eviction control ordinances passed in Richmond and Mountain View.

Rent control was strengthened in Berkeley, Oakland, and East Palo Alto.

Voters passed Measure U1 in Berkeley, which increases the business license tax on landlords with five or more residential units. The tax increased from 1.1 percent to 2.9 percent of gross receipts. The tax may not be passed onto tenants.

In East Palo Alto, this same business license tax is 1.5 percent of the gross receipts of landlords.

Rent control was defeated in Burlingame and San Mateo and Alameda. But a rent review and stabilization ordinance was passed by voters in Alameda.

The Santa Barbara City council considered it in March 2017 but rejected pursuing it as a policy and will consider issues associated with rental mediations and inspections.

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.