Manfred Keil and Mark Schniepp

May 2025

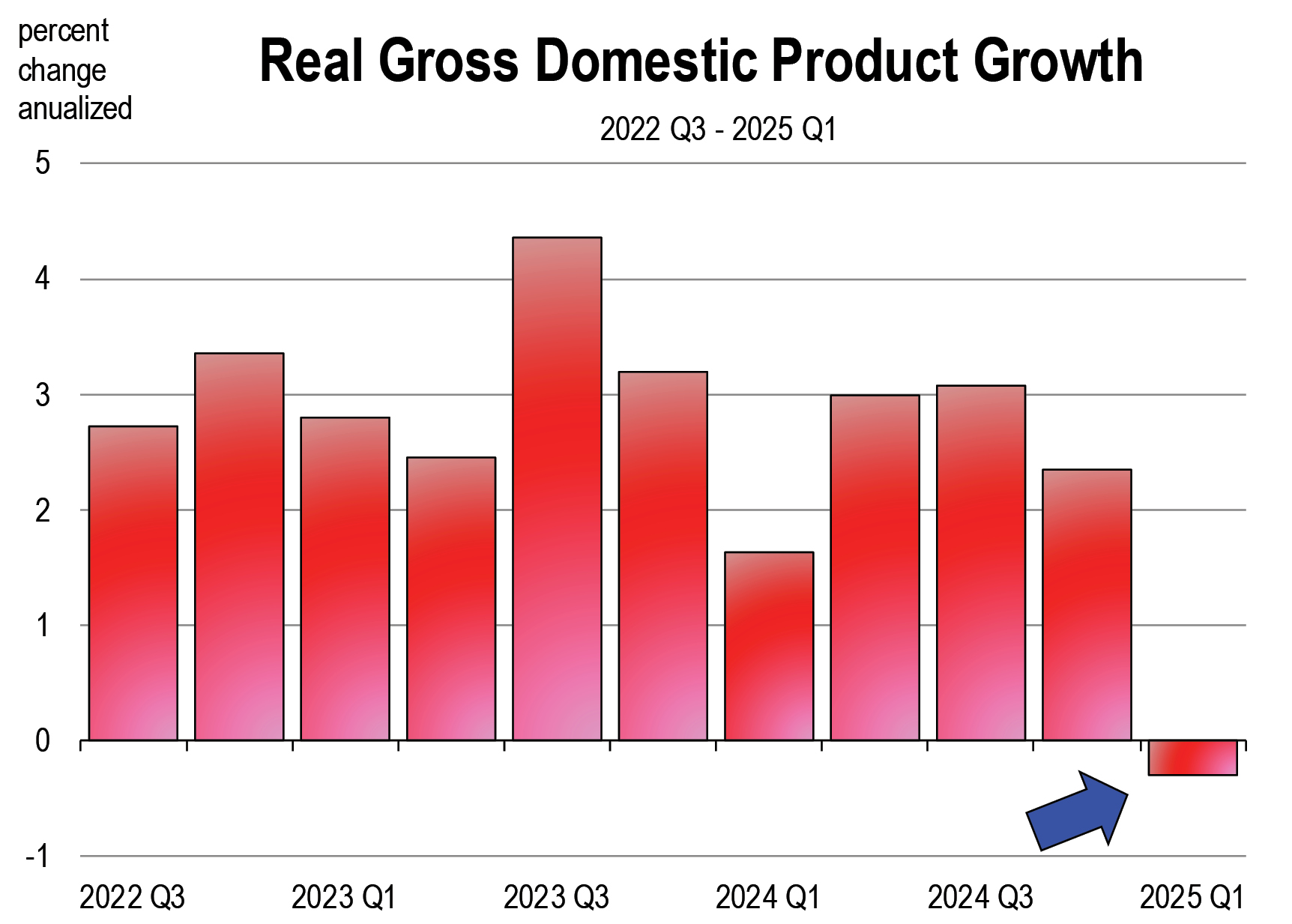

A host of important economic statistics became available last week to give us insights into the current state of the U.S. economy. There was negative

quarterly growth of real GDP, with output shrinking by 0.3 percent; the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 4.2 percent but job numbers showing a better than expected increase of 177,000; and the yearly inflation rate fell slightly towards the Fed’s target judging by both the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure and the headline making consumer price index (2.3 percent and 2.4 percent respectively).

The recent data deliver a mixed picture and does not yield a clear answer of where we are heading. Certainly, these statistics alone do not justify forecasts of a downturn later in the year. It is the uncertainty that has raised the prospect of recession in 2025. The so-called soft-landing (reduction in inflation without causing a recession) is still a possibility, and the dreaded stagflation scenario (low GDP growth with stubborn inflation) has not materialized, yet.

Some have pointed to the fact that the negative growth in GDP was related to both households and firms hoarding imported goods to beat tariff related future price increases. After all, imports rose by over 41 percent (annualized) from the last quarter, which is of an order of magnitude only seen twice over the half century. Unfortunately, this is wrong, since GDP only measures domestic production or aggregate demand for domestic goods. GDP is neutral to imports, unless there are measurement errors.

Two quarters of negative GDP growth are commonly perceived as the start of a recession. This suggests that if we observe negative real GDP growth in 2025 Q2, then the recession started in the current quarter. Unfortunately, this definition of a recession is false. It is the dating committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) that determines the start and end of recessions, and it does so by month. The Great Recession of December 2007 to July 2009 would not have been labeled such if you went by the “two quarter” definition: there was positive economic growth during the second quarter of 2008. Unfortunately the NBER typically publishes the start of a recession with a considerable delay: it took the committee 12 months (December 2008), to date the peak of the previous economic expansion. This does not make it useful to pursue alternative policies or to prepare for a downturn.

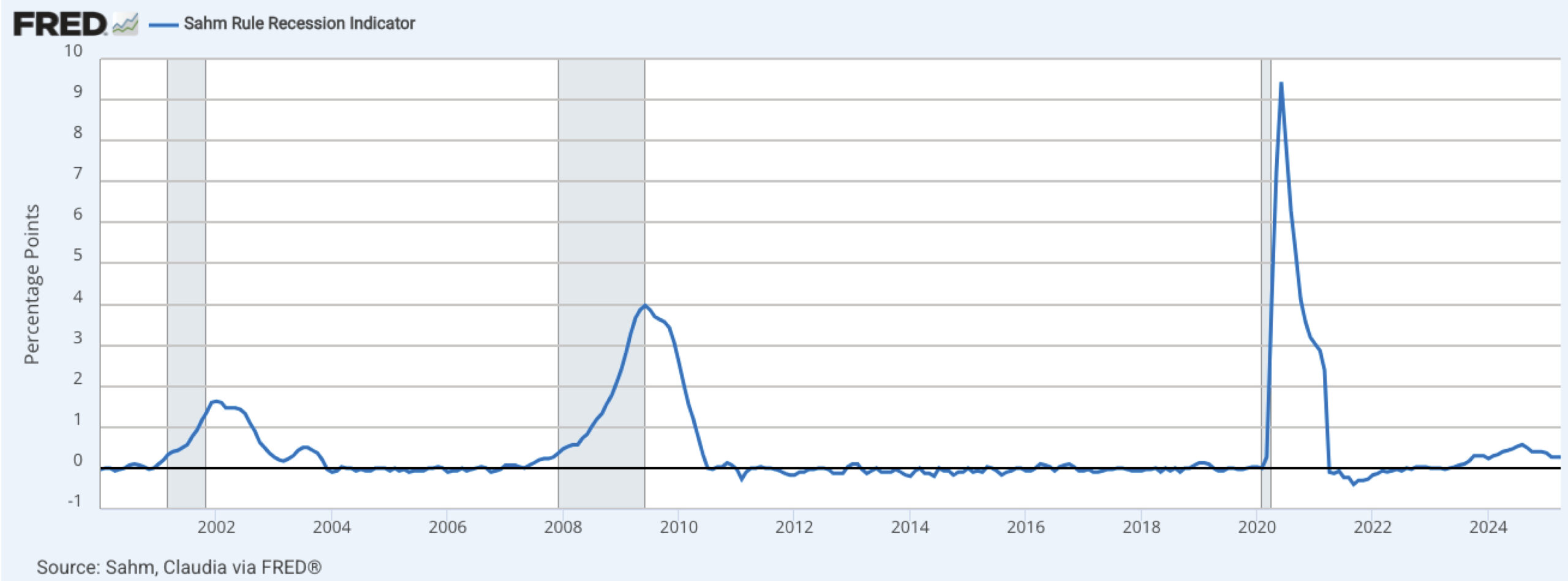

One of the earliest signs that we are in a recession will come from the so-called Sahm rule developed by Claudia Sahm in 2019 to identify early stages of a recession. The rule focuses on the unemployment rate and a warning is triggered when the rate rises by a certain amount relative to where it was over the last year. There have been almost no false positives using the Sahm rule to predict a recession over the last 80 years. The measure today is not indicating a recession, and even another quarter of negative growth is unlikely to generate one.

A chart of the Sahm rule in action

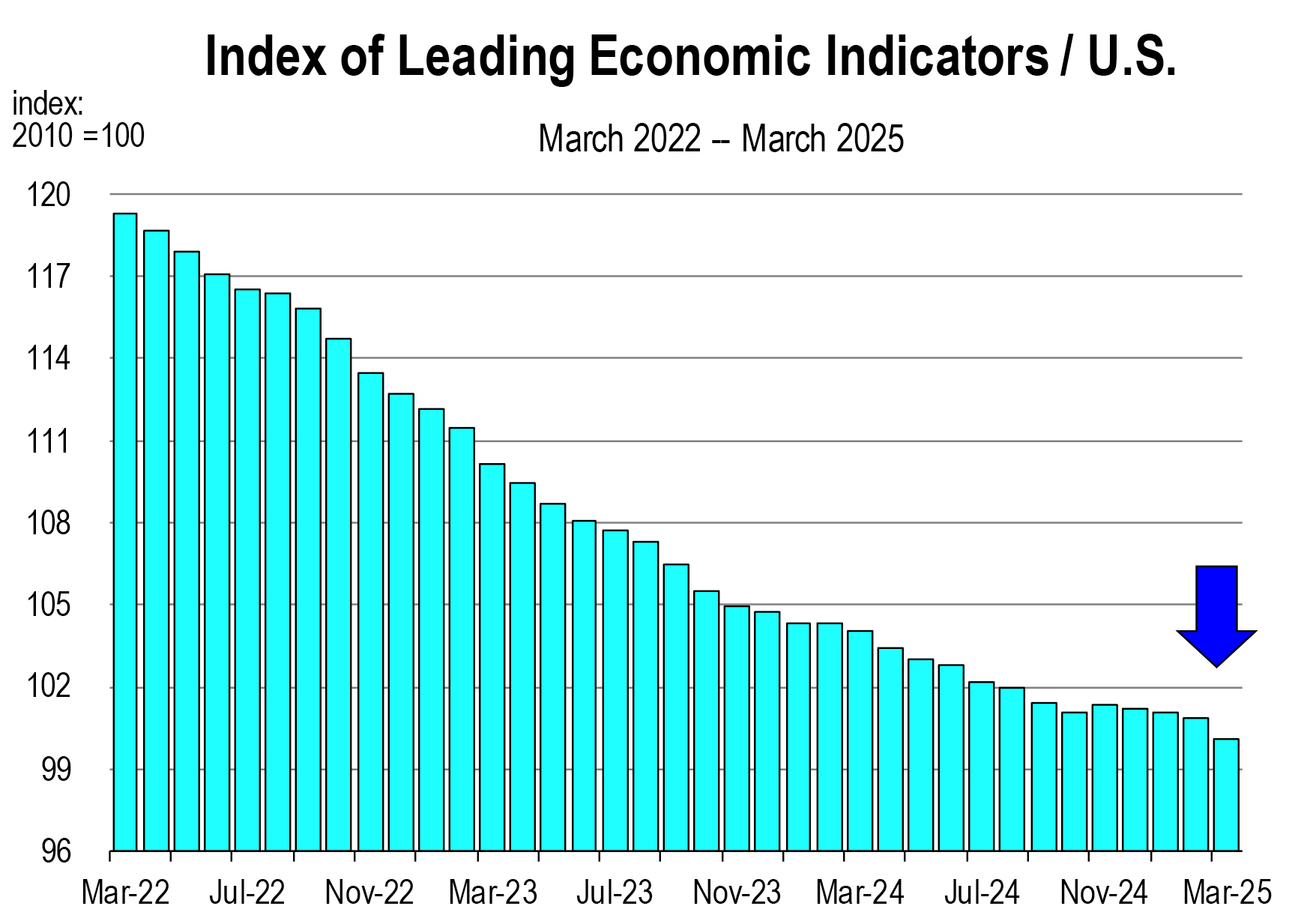

There are other “sensors” that, similar to a volcano outbreak, predict disaster. The Conference Board summarizes these in a so-called Index of Leading Economic Indicators. The series is a weighted average of twelve measures including the S&P 500 composite index, housing starts, consumer sentiment index, new durable goods orders, etc., and, as a rule of thumb, rings alarm bells of a subsequent recession if it turns southward for a series of consecutive months. This statistic is implying we may be reaching the threshold for recession.

Finally, 45 percent of economists polled by the Wall Street Journal have forecasted a recession within a year. However, this is the same bunch who, in October 2022, felt that a downturn was imminent (63 percent at that time). This became known as the “Godot Recession.” In Samuel Becket’s play ‘Waiting for Godot,’ the messenger repeatedly arrives to announce that Mr. Godot could not make it today but surely would come tomorrow.

Consumers are clearly on edge as the consumer confidence and sentiment indices have fallen to recession territory levels. Given current fundamentals, it is difficult to forecast a reversal in confidence. But movements in consumer sentiment, even large ones like those seen recently, do not necessarily generate similar moves in real consumer spending. If there was such a correlation, we would undoubtedly be in a recession by now.

The case for a recession in 2025 stems from ongoing uncertainty which is delaying domestic investment decisions (and therefore domestic business spending), and less government spending by the administration to directly address corruption, fraud, and waste. However, domestic consumption – the largest component of GDP and the main driver of growth – is less likely to weaken. This is because consumer spending remained resilient in the first quarter and a near fully employed labor market continues to support household incomes, enabling continued consumer spending throughout the year.

The resilience of consumer spending, amid contractions in domestic investment due to prolonged uncertainty and government spending from overdue government downsizing, could result in another one or even two quarters of negative GDP growth this year, potentially prompting the NBER to declare a recession. However, given that consumer spending remains stable, the most likely scenario based on the current evidence is a recession that would be shallow and brief, with its duration limited by the eventual resolution of uncertainty.

The most likely baseline outlook for the economy is that the Trump administration’s economic policies will diminish the U.S. economy but not derail it. It is our belief that the president will pivot on his policies in time to avoid recession. This occurs when it becomes clear that without a course correction, stock prices will decline further, consumers would become so fearful they stop spending, and the economy would suffer a bona fide downturn.

Manfred Keil is Chief Economist, Inland Empire Economic Partnership, and Associate Director, Lowe Institute of Political Economy, Robert Day School of Economics and Finance, Claremont McKenna College. Mark Schniepp is the Director of the California Economic Forecast.

The California Economic Forecast is an economic consulting firm that produces commentary and analysis on the U.S. and California economies. The firm specializes in economic forecasts and economic impact studies, and is available to make timely, compelling, informative and entertaining economic presentations to large or small groups.